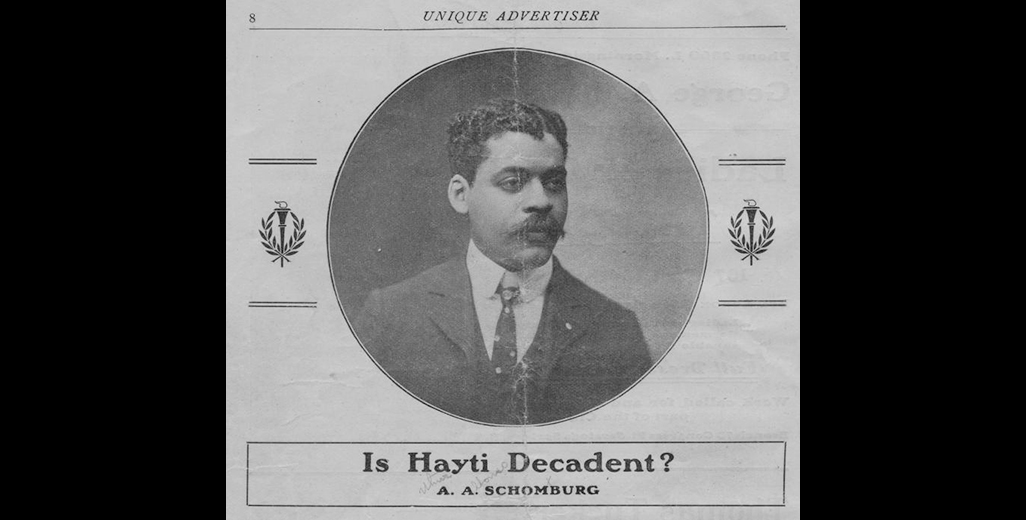

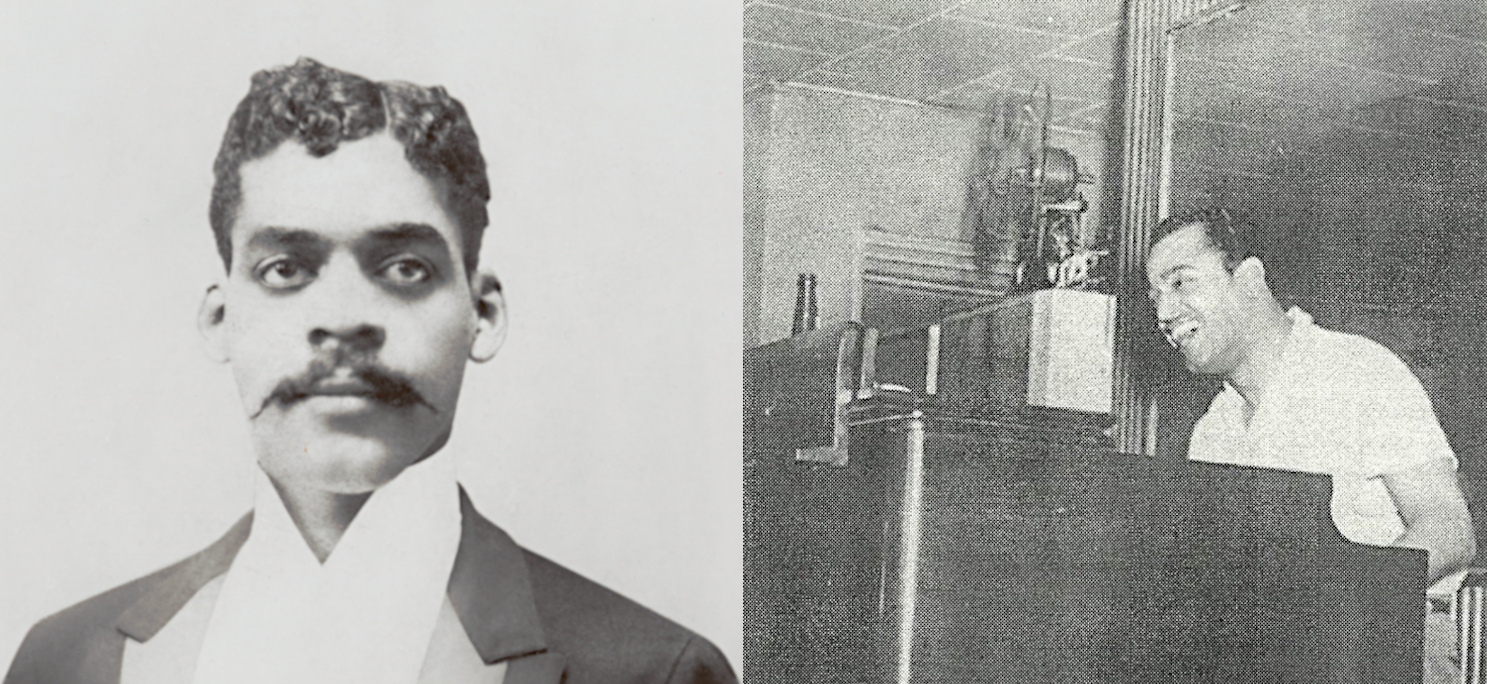

Arturo Schomburg, 1896.

Photo: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture/The New York Public Library.

Stepping into the Public Sphere: Arturo Schomburg's Letters to the New York Times

August 29, 2024

by Vanessa K. Valdés, Author and Educator

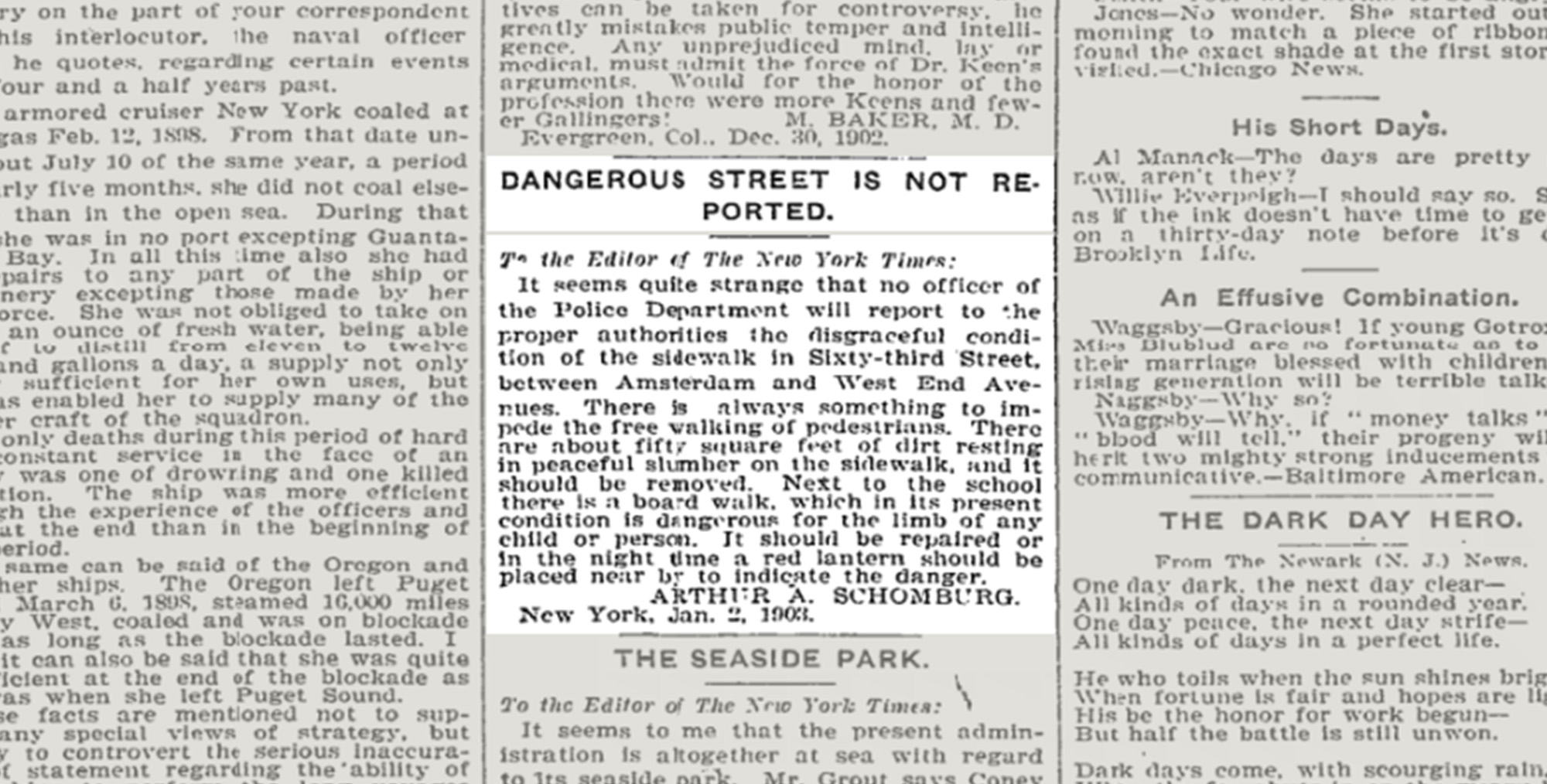

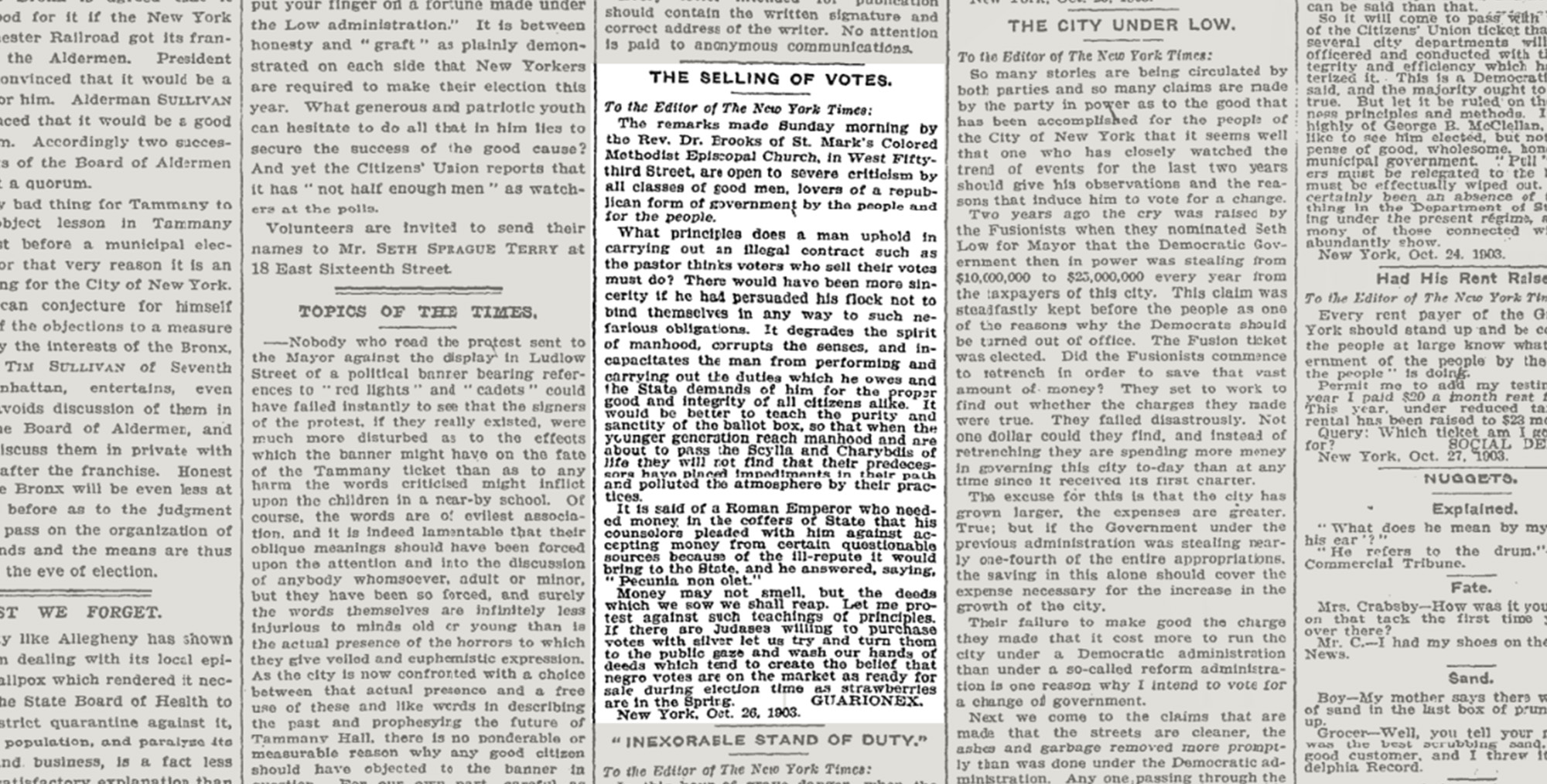

On January 2, 1903, one Arthur A. Schomburg wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times urging the New York Police Department to report to the proper authorities a broken sidewalk on Sixty-third Street, between Amsterdam and West End Avenue. He writes, “Next to the school there is a board walk, which in its present condition is dangerous for the limb of any child or person. It should be repaired or in the night time a red lantern should be placed near by to indicate the danger.”1 Schomburg had lived in San Juan Hill for three years, from 1897-1900, and though he had moved out, perhaps in response to the Tenderloin Riot that had taken place in 1900, Schomburg continued to frequent the neighborhood.2 This is evident by another letter to the editor published on October 31, 1903, in which he rails against a sermon by Reverend Doctor William H. Brooks of the St. Mark’s Methodist Episcopal Church on West Fifty-Third Street.3 Schomburg comments that the sermon, which centered on the sale of votes for political office, was “open to severe criticism by all classes of good men, lovers of a republican form of government by the people and for the people.” He goes on to say that the vending of the franchise “degrades the spirit of manhood, corrupts the senses, and incapacitates the man from performing and carrying out the duties which he owes and the State demands of him for the proper good and integrity of all citizens alike.” In a local political environment that was deeply racist, one in which “city authorities treated Black people as the aggressors rather than the victims of violence” and in which “white New Yorkers followed the lead of their southern compatriots in disparaging the viability of Black freedom and equality,”4 Schomburg reveals a deep and abiding faith in the United States political system and its form of government.

Little attention has been paid to the sixteen letters Schomburg wrote to the New York Times from 1901-1905.5 Yet, as Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof writes, these correspondences represent, for Schomburg, “an audacious leap into the debates of the public square,”6 particularly when one notes that he writes about US domestic and foreign policy in the first decade of the twentieth century, when the United States was staking a claim in empire. Schomburg’s presence in New York may itself have been a result of US expansion into the Caribbean: though the motivation for his move to the city in 1891 remains unknown, we do know he arrived with letters of reference, including one from José González Font, a Black Puerto Rican, like Schomburg himself, who was a significant contributor to the spread of print culture on the island and for whom Schomburg had worked in his print shop.7 Schomburg presented these letters to Afro-Puerto Rican Flor Baerga and Afro-Cuban Rafael Serra, founders of Los Independientes, a political club dedicated to the revolutionary efforts of independence of Puerto Rico and Cuba from Spain.8 Men and women on both islands had been fighting to end their colonial relationship with Spain since at least 1868, which saw the Grito de Lares in Puerto Rico and the Grito de Yara in Cuba; these battles had been ongoing for more than two decades by the time Schomburg joined the fight. Within his first year in New York, he was involved with Club Borinquen and the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (the Cuban Revolutionary Party), and co-founded Las Dos Antillas, a reference to both islands; all of these groups were raising money to support rebels on the ground fighting the Spanish militia.9

In the same year of 1892, Schomburg was initiated into the Prince Hall Masons in the El Sol de Cuba Lodge, Number 38 in Brooklyn; founded by Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants, this was a Spanish-speaking lodge that also served as a focal point for revolutionary activity.10 The Prince Hall Masons remains a fraternal order that unites Black men across national boundaries; founded in the United States in the late eighteenth-century, lodges quickly spread throughout the Americas, including the Caribbean.11 Black Freemasonry was an instrumental force in how these men understood themselves as men, particularly in former slave-holding societies that had exhibited trouble in incorporating Black populations into their citizenry, including the United States.12 They understood that being productive citizens in this country meant being actively involved in politics and being leaders of their local communities; at the start of the nineteenth century, the Prince Hall Masons were a part of those who would be called Race Men, tributes to the Black race. They are men who “inspire pride; their work, their actions, and their speech represent excellence.13

We see the impact of the Freemasons on Schomburg in the October 31, 1903 letter, cited above: the thought that a price would be attached to the vote, a right that African American communities across the country had fought for in the aftermath of the US Civil War, was a horror to him, one that betrayed the responsibilities of citizenship. From expressing his antipathy for Black emigration to Africa14 to reflections on the US obligations to the Philippines during and after the Philippine-American War (1899-1902)15, and from examinations on the legal status of Puerto Ricans during a time of the Insular Cases16 to denunciations against the domestic terrorism waged against African Americans17, Schomburg wrote about a wide swath of topics. Later in his life, Schomburg would go on to write articles that appeared in such publications as the NAACP’s Crisis and the National Urban League’s Opportunity Journal;18 these letters that appeared in the pages of the New York Times were his first forays into a world of the public intellectual.

* Schomburg published this letter using the pseudonym “Guarionex” as he did four others within the sixteen letters to the editor of the New York Times. Guarionex was a Taíno cacique of Ayiti-Kiskeya-Bohio, the island renamed Hispaniola by the Spanish shortly after Columbus’s arrival; he was killed by the Spanish in 1502. Eugenio María de Hostos included him as the protagonist of his novel La peregrinación de Bayoán (1863), one calling for the unification of the Caribbean. In using this as his pseudonym, Schomburg was honoring the struggles against Spanish colonialism.

Notes

1 Born Arturo Alfonso Schomburg in San Mateo de Cangrejos, Puerto Rico on January 24, 1874, a year after the abolition of slavery on the island, he moved with his mother Mary Joseph to New York City in April of 1891. Within a decade, he signed his name “Arthur A. Schomburg”; over the course of his life he would also sign it “A.A. Schomburg” before returning to “Arturo A.” in the years before his death on June 10, 1938. Schomburg (05 Jan 1903), n.p.

2 Elinor Des Verney Sinnette details that Schomburg lived at 220 West 62nd Street with his first wife, Bessie (née Elizabeth), and their sons Máximo Gomez (b. 1897), who died within months; Arthur Alfonso Jr. (b. 1898), and Kingsley Guarionex (b. 1900). The 1900 census also lists his mother-in-law, Sarah Hatcher, as living with the family; Sean Khorsandi, executive Director of Landmark West!, shared this with me in private correspondence on December 19, 2023. The speculation about the motivation for the family leaving San Juan Hill emerges from private correspondence on June 30, 2023 between myself and Laura C. Helton, author of Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History (2024), the first chapter of which is dedicated to Schomburg.

3 Schomburg published this letter using the pseudonym “Guarionex” as he did four others within the sixteen letters to the editor of the New York Times. Guarionex was a Taíno cacique of Ayiti-Kiskeya-Bohio, the island renamed Hispaniola by the Spanish shortly after Columbus’s arrival; he was killed by the Spanish in 1502. Eugenio María de Hostos included him as the protagonist of his novel La peregrinación de Bayoán (1863), one calling for the unification of the Caribbean. In using this as his pseudonym, Schomburg was honoring the struggles against Spanish colonialism. For more, see Arroyo 155-168.

St. Mark’s Colored Methodist Church was one of the first Black churches in New York City; organized only six years after the conclusion of the US Civil War in 1871 and originally located on Broadway between Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth streets, it moved to the West Fifty-Third Street location in 1895.

4 Sacks 42, 43.

5 To my knowledge, only two researchers have referenced these letters in passing: Elinor Des Verney Sinnette and Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof (2019). All of these letters are publicly available at the New York Times Article Archive: https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/ref/membercenter/nytarchive.html

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has published a research guide that includes a bibliography of all of his writings: https://libguides.nypl.org/arturoschomburg/writings

6 Hoffnung-Garskof (2019) 270.

7 Sinnette 17; Hoffnung-Garskof (2019) 45. The letter itself can be found in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

8 Sinnette 20; for a short biographical sketch of Serra, see Valdés 38-40. For more on the Afro-Cuban and Afro-Puerto Rican communities in New York City that were involved with the efforts for freedom from Spain in the late nineteenth century, see Hoffnung-Garskoff (2019).

9 These efforts ended with the United States involvement in these efforts in 1898; at the conclusion of the Spanish-Cuban-American War, the United States gained several of Spain’s dwindling colonial possessions in the Atlantic (Cuba and Puerto Rico) and the Pacific (Guam and the Philippines). Only its colony of Spanish Guinea, a country in West Africa, remained; it gained its independence seventy years later in 1968. For an overview of the Cuban and Puerto Rican efforts for independence from Spain in the nineteenth century, see Valdés 27-54.

10 For more on El Sol de Cuba Lodge, see Hoffnung-Garskoff (2001) 27-39, and Arroyo 155-168; for more on Schomburg’s life as a Mason, see Sinnette 26-27, 57-61 and Valdés 59-64.

11 For more on the history of Prince Hall Masonry in the United States, see Wallace 54-64; for more on Freemasonry in the hispanophone Caribbean, see Arroyo.

12 African Americans only gained citizenry with the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution in 1868; US Black men gained the right to vote two years later, with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. For more on the incorporation of Black populations into the citizenry of Latin American countries, see Andrews.

13 Neal 169; for more on Race Men, see Carby. For more on Black manhood, see Neal and Wallace.

14 Schomburg (03 Sept 1901).

15 Schomburg (24 Nov 1901) and (08 June 1902).

16 Schomburg (09 Aug 1902) and (29 March 1903). The Insular Cases were a set of court rulings that determined that Puerto Rico was a non-incorporated territory of the United States, laying the foundation for its continued colonial status; for more, see Sparrow.

17 Schomburg (24 May 1903); (28 June 1903); (16 Aug 1903); (18 Oct 1903); (21 Aug 1904).

18 For more on these writings, see Valdés 71-90.

Bibliography

Andrews, George Reid. Afro-Latin America, 1800-2000. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Arroyo, Jossianna. Writing Secrecy in Caribbean Freemasonry. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Carby, Hazel. Race Men. Harvard University Press, 1998.

Hoffnung-Garskof, Jesse. Racial Migrations: New York City and the Revolutionary Politics of the Spanish Caribbean. Princeton University Press, 2019.

--. “The Migrations of Arturo Schomburg: on being Antillano, Negro, and Puerto Rican in New York 1891-1938.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21:1 (2001) 3-49.

Neal, Mark Anthony. Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities. New York University Press, 2013.

Sacks, Marcy. Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Schomburg, Arthur A. [Guarionex]. Letter. “The Lynchings in Georgia,” The New York Times, August 21, 1904, 8. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1904/08/21/120287908.html?pageNumber=8

--. [Guarionex]. Letter. “The Selling of Votes,” The New York Times, October 31, 1903, 8. https://www.nytimes.com/1903/10/31/archives/the-selling-of-votes.html?searchResultPosition=1

--. Letter. “Tillman Trial and Verdict,” The New York Times, October 18, 1903, 25.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/10/18/102026658.html?pageNumber=25

--. Letter. “Points on Lynching for John Temple Graves,” The New York Times, August 16, 1903, 9. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/08/16/102018170.html?pageNumber=9

--. Letter. “Lynching a Savage Relic,” The New York Times, June 28, 1903, 8.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/06/28/101311070.html?pageNumber=8

--. Letter. “The Negro and His Rights,” The New York Times, May 24, 1903, 26.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/05/24/102001741.html?pageNumber=26

--. Letter. “Status of Porto Ricans,” The New York Times, March 29, 1903, 27.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/03/29/101985416.html?pageNumber=27

--. Letter. “Dangerous Street is not Reported,” The New York Times, January 5, 1903, 8. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/01/05/101964067.html?pageNumber=8

--. Letter. “Questions by a Porto Rican,” The New York Times, August 9, 1902, 8.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1902/08/09/118475138.html?pageNumber=8

--. Letter. “The Philippine Question,” The New York Times, June 8, 1902, 6.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1902/06/08/118472967.html?pageNumber=6

-- Letter. “A Philippine Republic Suggested,” The New York Times, November 24, 1901, 6.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1901/11/24/117977557.html?pageNumber=6

--. Letter. “Takes Issue With Bishop Turner,” The New York Times, September 3, 1901, 6. https://www.nytimes.com/1901/09/03/archives/takes-issue-with-bishop-turner.html?searchResultPosition=5

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. "Font, Jose Gonzalez" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1904 - 1938. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/034ddf60-31ee-013b-9071-0242ac110003

Sinnette, Elinor Des Verney. Arthur Alfonso Schomburg: Black Bibliophile and Collector. New York Public Library and Wayne State University Press, 1989. 23.

Sparrow, Bartholomew. The Insular Cases and the Emergence of American Empire. University Press of Kansas, 2006.

“St. Mark’s United Methodist Church.” The New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, https://www.nycago.org/Organs/NYC/html/StMarkMeth.html. Accessed 19 May 2024.

Valdés, Vanessa K. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. State University of New York Press, 2017.

Wallace, Maurice O. Constructing the Black Masculine: Identity and Ideality in African American Men’s Literature and Culture, 1775-1995. Duke University Press, 2002.