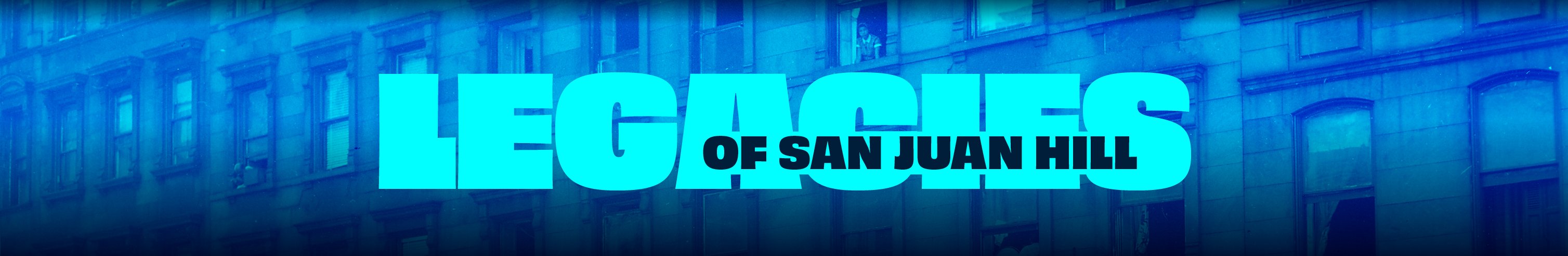

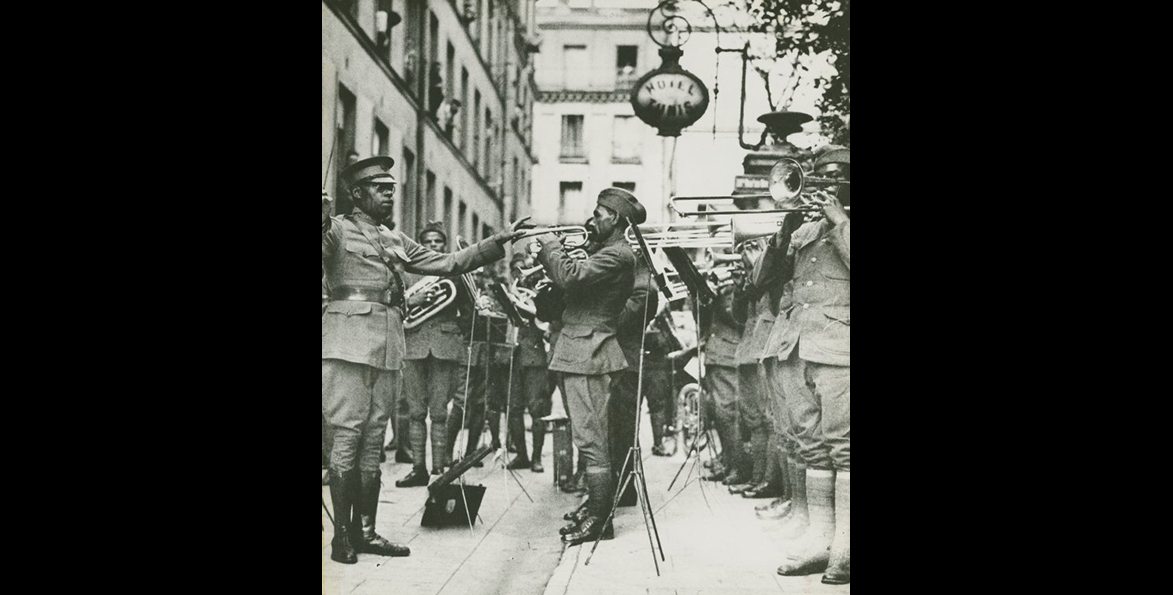

Clef Club Band, 1914.

Photo: New York Public Library.

James Reese Europe's Musical Journey

June 10, 2024

by Michael D. Dinwiddie, Professor at New York University

In his lifetime, James Reese Europe (1880-1919) was celebrated as an exceptional composer, conductor, band leader, and entrepreneur. A visionary African American artist whose profile fit the “politics of respectability” paradigm, 1 Europe embraced an agenda of diversity, inclusion and equality long before those concepts were codified into the philosophy of racial progress that is so widely accepted today. He was proud of his heritage, and in a 1914 interview with a New York Post reporter, Europe declared that “…we colored people have our own music, that is part of us…it’s the product of our souls.” 2 Through his unique synthesis of ragtime, spirituals and blues, he created a mélange that laid the groundwork for what we now categorize as “jazz.”

James was born the fourth of five children to Lorraine and Henry Europe on February 22, 1880 in Mobile, Alabama. While his mother Lorraine’s family had been free for generations, father Henry was not emancipated from slavery until the Civil War ended in 1865. Ambitious and determined to take care of his family, Henry “[worked] at a variety of temporary occupations including teaching, newspaper reporting, and barbering.” His loyalty to the Republican Party earned him “a clerkship in the…Post Office in mid-1872.” 3 Lorraine, a homemaker, “played the piano and had learned musical notation at least well enough to provide each of her children with their first music lessons. 4 Jim and his siblings—John, Minnie, Ida and Mary—all showed…both aptitude and continuing interest.” Henry was a self-taught musician who “could play about everything that would emit a sound when properly coaxed, and he wasn’t particular what.” 5

In 1889, Henry accepted a position with the Internal Revenue Service and moved his family to a rowhouse in Washington, DC. A few doors down lived John Philip Sousa, the renowned conductor and composer of the U.S. Marine Corps Band. Sousa encouraged his band members to take on pupils who showed a special gift for music. James and Mary Europe were fortunate to have Enrico Hurlei, Sousa’s assistant conductor, as their instructor. 6 Reid Badger posits that James’s family background and “…this early training provided the foundation for [his] later success as a composer of marches and as a leader of a military band during World War I. 7 In 1894, when he was 14, “Jim entered a citywide contest in composition and came in second; his younger sister [Mary] took the top prize. 8

In 1900 James’s older brother John relocated to New York City where he quickly found work as a professional pianist. During this era, the theatre kept hundreds of Black entertainers gainfully employed. "Nearly all the leading vaudeville, speciality [sic], and variety shows… engaged first-class colored talent” each season. Black Patti’s Troubadours boasted a company of 60 performers who traveled in their own private railcar, as did McCabe’s minstrels and other troupes. In Dahomey, a musical comedy produced by African Americans Bert Williams and George Walker, was such a hit on Broadway that it transferred to London’s Shaftsbury Theatre for several months and played a command performance at Buckingham Palace. 9

Encouraged by the burgeoning scene and “…attracted by the possibility for obtaining employment with one of the musical-show companies, Jim soon followed [his brother] John to New York.” 10

Seeking employment opportunities, James frequented The Marshall Hotel, which was located at 127-129 West 53rd Street just south of the San Juan Hill district. “Known for its wonderful cuisine and its entertainment, the [Marshall] attracted the best people of both races who rubbed elbows there nightly. Here also came white actors, musicians, and composers from the nearby Broadway theater district, to see and be seen. Jim soon learned that the bar was packed with entertainers waiting for calls to go out all over the city, for it was known that one could always find dancers, musicians and singers at the Marshall. 11

Hotelier Jimmie Marshall was a popular and jovial host whose adjoining brownstones were “a very popular gathering place that attracted elite patrons in search of talented artists. 12 Denizens of the hotel included theatre luminaries Bob Cole, Billy Johnson, Bert Williams, George Walker, and the Johnson brothers--James Weldon and J. Rosamond. It was here that James met John Love, secretary to Rodman Wanamaker, scion of the wealthy Philadelphia department store family. Love hired James to supply a string quartet for Rodman’s three-day birthday party in Atlantic City, and Rodman was so impressed with the entertainment that lucrative and steady work followed with other wealthy families who insisted on music by James Reese Europe. Private parties and society events in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston for the likes of the Goulds, Astors, and Vanderbilts made for steady and lucrative employment. 13 For the next few years, James was in such demand that he booked himself into two or three events each evening, leaving much of the conducting to experienced colleagues Will Vodery and Ford Dabney. 14

But James, perhaps influenced by his childhood exposure to Sousa, had a much loftier aim. “He was a good piano player,” Tom Fletcher recalled, “but he wasn’t satisfied just to be a good piano player, so he began to study all phases of music: theory, harmony, and how to be a conductor. He was so interested in his studies that while playing an engagement at the Brevoort Hotel in New York one evening, he brought a book of his lessons on the job and placed it on the piano so he could study while he worked.” 15

In 1906, his opportunity to conduct a first-class musical comedy arrived with The Shoo-Fly Regiment, written by James Weldon and J. Rosamond Johnson, and comedian/playwright Bob Cole. The plot revolves around Hunter Wilson, who puts aside his teaching career to come to the defense of his country in the Spanish-American War. His fiancée Rose disapproves and breaks off the engagement. In the Philippines, Hunter shows bravery in battle, returns a hero, and Rose agrees to marry him. Black musical comedy was breaking new ground and audiences were starting to see more complex stories about African Americans presented on stage. While today it might seem a conventional love story, the notion of a heroic Black soldier with a romantic entanglement was considered a breakthrough from the blackface minstrelsy that had dominated the American stage for decades. According to Lester Walton of the New York Age, “Those who came to see the ordinary buffoonery of the average Negro company remained to wonder at, or be entertained by, and to ponder over a most delightful entertainment.” The Shoo-Fly Regiment put a positive spin on the Black veterans who had fought with Teddy Roosevelt at Cuba’s San Juan Hill. The out-of-town tour included Washington, DC, Indianapolis, and Philadelphia “with a cast of fifty” on its way back to New York. 16 James was proud of his work on a project which presented African Americans in a respectable light.

For their next project, The Red Moon, Bob Cole and the Johnson Brothers invited James to continue as a conductor. The love story followed the escapades of Plunck, a show manager, and Slim, a piano player, as they rescued the biracial Minnehaha from capture and kidnapping. While comedic in tone, the harsh reality of the slave past must have held special resonance for James, whose own father had been born in captivity. Conversely, the play tackled the fraught subject of marriage between different racial groups, and featured romantic love lyrics throughout its libretto. 17

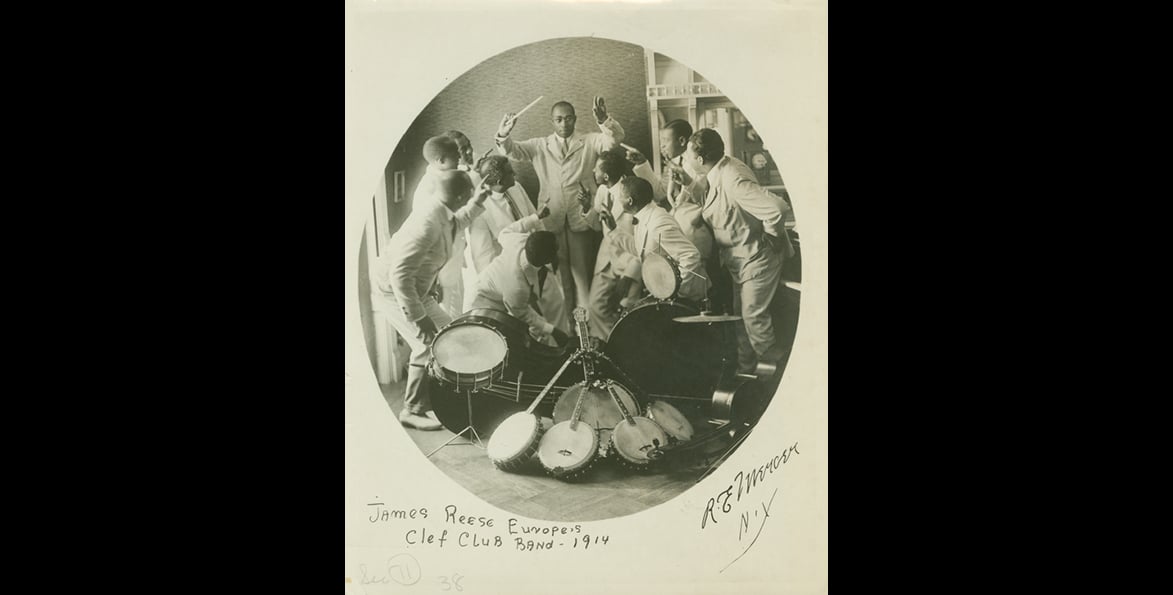

James Reese Europe was was a founding member of The Frogs in 1908, a fraternal organization of African American producers and entertainers who were determined to change the depiction of Blacks on the stage. 18 Two years later, he founded the Clef Club, “which served as a social club, booking agency, and musicians’ union and controlled the music and entertainment business.” 19 When he brought the Clef Club Orchestra to Carnegie Hall in 1912, it was the first time that music by African American composers had been presented on that august stage. 20

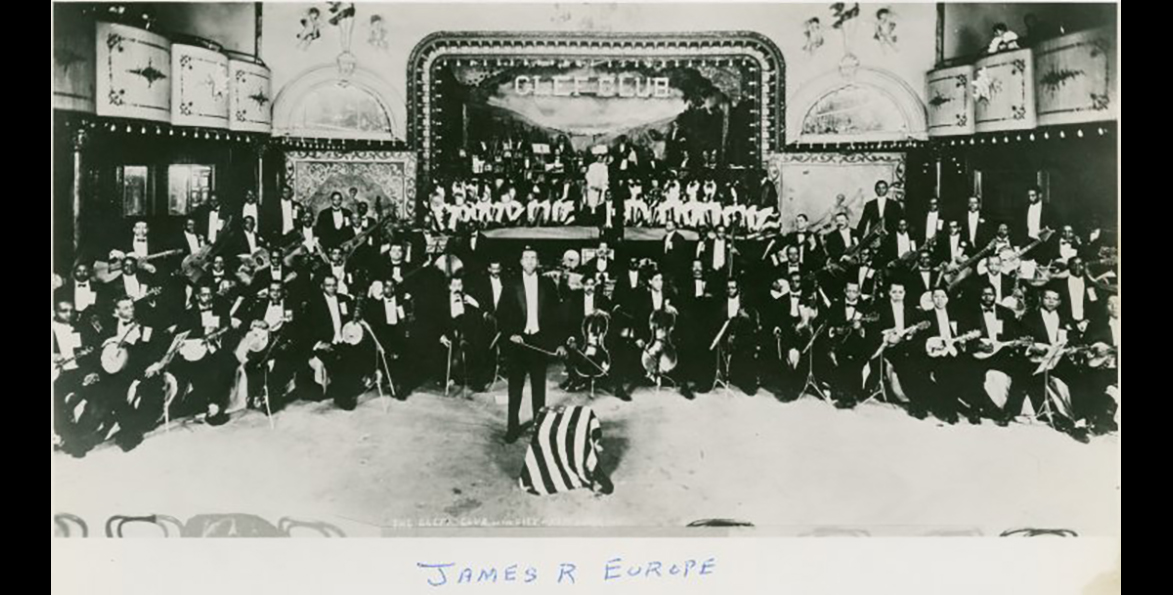

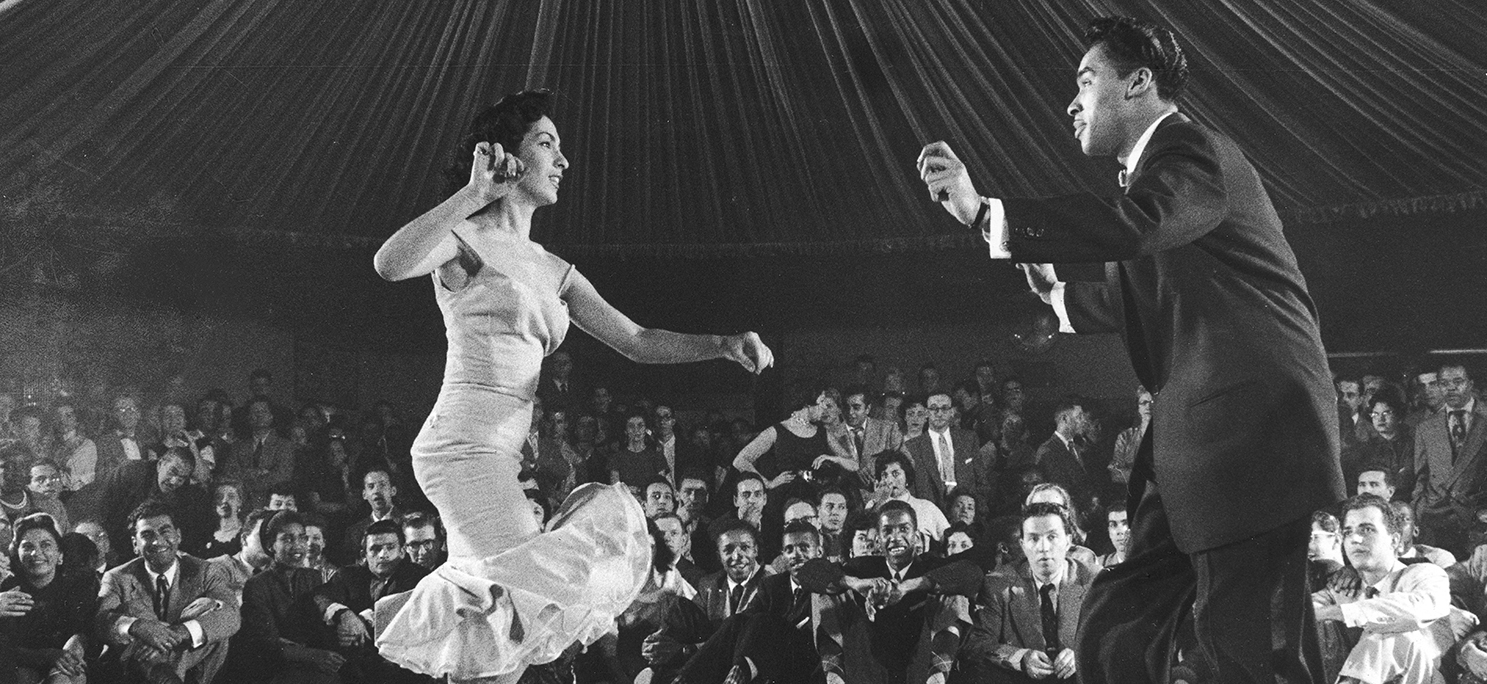

When exhibition dancers Vernon and Irene Castle first heard the Clef Club Orchestra at a festive ball in Newport, RI, they were immediately entranced by the unique syncopated rhythms. “The dancing of the Castles was called jazz dance” according to Dr. Samuel Floyd, who goes on to point out that “…Europe’s bands--at least the ones that were recorded--did not play jazz as we have come to know it. But whether or not Europe’s band played jazz, it fairly shouted, with its brassy trumpets, smearing trombones, and additive and cross-rhythms, all of which can be heard on “Memphis Blues” and “Clarinet Marmalade.” 21 James wrote “Castle House Rag” in tribute to the Castle House [School] for the Teaching of Correct Dancing, “where the more staid versions of black dance were introduced to white society and where the ‘rules of good taste were sufficiently strict to make the new dances acceptable.’” Europe was the exclusive musical conductor and arranger for the Castles. On a whirlwind tour of 30 cities, they introduced the Fox Trot, a two-step which Europe had created by slowing down W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues” and combining it with a dance he had seen as a child in DC, called "Get Over It, Sal." 22

As World War I commenced, Nebraska National Guard Colonel William Hayward was assigned to help build a Black National Guard unit in Harlem. “The 15th Infantry Regiment (Colored) … thus began its existence with one white officer and little else: no rifles, ammunition, uniforms, armory to drill in, headquarters for recruitment, or troops.” James Reese Europe enlisted as a private and was assigned to a machine gun company. 23 Hayward “understood from the first that successful recruiting depended in large part on showmanship, and that meant parades and uniforms and the stirring music of a military brass band.” 24 He invited James to create a marching band. But Europe turned him down. Military regulations limited the size of bands to 28 pieces, and James—remembering Sousa—needed at least 40+ musicians to achieve the right sound. Also, Clef Club musicians who enlisted would have to take a hefty pay cut to work for Uncle Sam. Undeterred, Hayward convinced a wealthy businessman to write a check for $10,000* so that James would have the necessary funds to build his ideal marching band. Meeting the challenge, Europe set about creating an ensemble that he would be proud to conduct. His penchant for superior musicians led him to Puerto Rico, where he conducted auditions for “clarinetists, flutes, saxophones, and one or two other instruments…” James knew that their instruments would serve the same purpose in a military band that string instruments served in a symphony orchestra. 25

After the United States declared war on Germany, the 15th Infantry (newly christened the 369th Regiment) landed in France on January 1, 1918. After they disembarked from the ocean transport, they played Pocahantas, their syncopated version of La Marseillaise. “At first, to the surprise of the Americans, and especially, the band members, the French soldiers seemed not to recognize the strains of their own national anthem.” Suddenly, “as the band played eight or ten bars there came over their faces an astonished look, quickly alert snap-into-it-attention and salute by every French soldier and sailor present.” 26 This was the same reaction that the band elicited as they traveled thousands of miles performing throughout the war-torn nation, lifting the morale of soldiers and citizens alike. The 369th spent 191 days in the trenches and was awarded 171 Croix de Guerres, more than any other American unit. They acquitted themselves honorably. Europe served as both a machine gun company officer and a conductor—in which capacity he was the first African American officer to lead troops in combat—and the fierce reputation as warriors earned them the nickname “Hell Fighters.” 27

A highlight for James “came in the Tuileries Gardens [in Paris] when we gave a concert in conjunction with the greatest bands in the world--the British Grenadiers’ Band, the band of the Garde Republicain (sic), and the Royal Italian Band. My band, of course, could not compare with any of these, yet the crowd, and it was such a crowd as I have never seen anywhere else in the world, deserted them for us.” He reminisced, “We played to 50,000 people, at least, and, had we wished it, we might be playing yet.” 28

When the Hell Fighters Band returned to the United States, they embarked on a triumphant nationwide tour. But near the end of their tour, tragedy struck when one of the band’s drummers pulled out a pen knife and wounded James Reese Europe in the neck. At the time, no one thought that the puncture was serious, and James left instructions for the next day’s performance as he stated, “I will have my wound dressed and I will be at the Commons… in time to conduct the band.” Later that evening, when band members arrived at the hospital, they were shocked when an orderly “sorrowfully whispered, ‘Lieutenant Europe is dead.’” 29

The next morning, “[newspapers] across the country carried the shocking report that the ‘King of Jazz’ had been slain.” Composer W.C. Handy lamented the fact that “The man who had just come through the baptism of war’s fire and steel without a mark had been stabbed by one of his own musicians…” 30

On the day of his funeral, an honor guard of musicians followed by “six automobiles carrying flowers sent by the Frogs, the Clef Club, Bert and Lottie Williams…and others” accompanied the flag-draped coffin as it traveled from Harlem down Seventh Avenue to St. Mark’s Episcopal Church on West 53rd Street. Located barely a block from the Marshall Hotel, St. Mark’s was a fitting place for his funeral. It was also walking distance for San Juan Hill residents who came to pay their respects. But even in their sadness, they recalled with admiration James’s triumphant Carnegie Hall Concert, when the Clef Club Orchestra filled New York’s bastion of high culture with the sounds of African American music. Eulogized as “the open sesame” and as “a benefactor, and a true friend” during the service 31, years later pianist Eubie Blake called him “the savior of Negro musicians…He was in a class with Booker T. Washington and Martin Luther King. I met all three of them.” What Blake was alluding to was the respectability and dignity that James brought to his many endeavors. “Before Europe, Negro musicians were just like wandering minstrels. Play in a saloon and pass the hat and that’s it…Jim Europe changed all that. He made a profession for us out of music. All of that we owe to Jim.” 32

For Further Reading

Badger, Reid. A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe. Oxford. 1995.

Brooks, Tim. Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birthing of the Recording Industry 1890-1919. University of Illinois, 2005

Fletcher, Tom. 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business. Da Capo Press. 1984.

Floyd, Samuel. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History From Africa to the United States. Oxford, 1995.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church 1880-1920. Harvard, 1994.

Jasen, David A. & Gene Jones, Spreadin’ Rhythm Around: Black Popular Songwriters, 1880-1920. Routledge, 2005

Johnson, James Weldon. Black Manhattan. Atheneum. 1930.

Kimball, Robert & William Bolcom, Reminiscing with Noble Sissle & Eubie Blake. Cooper Square Press, 2000.

Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in Blackface: A Source Book on Early Black Musical Shows. Scarecrow Press, 1980.

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans. Norton, 1971.

Woll, Allen, Black Musical Theatre: From Coontown to Dreamgirls. Louisiana Press, 1989.

Notes

1 Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church 1880-1920. (Harvard, 1994), 185.

2 Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birthing of the Recording Industry 1890-1919, 276.

3 Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime (Oxford, 1995), 13.

4 Badger, A Life, 16.

5 Badger, A Life, 10.

6 Badger, A Life, 20.

7 Badger, A Life, 20.

8 Badger, A Life, 22.

9 Tom Fletcher, 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business (Da Capo, 1984), 231.

10 Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime (Oxford, 1995), 26.

11 Tom Fletcher, 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business (Da Capo, 1984), 251.

12 Fletcher, 100 Years, 252.

13 Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime (Oxford 1995), 28.

14 Badger, A Life, 85.

15 Tom Fletcher, 100 Years of the Negro in Show Business (Da Capo, 1984), 252.

16 Henry T. Sampson, Blacks in Blackface (Scarecrow Press), 304.

17 David A. Jasen & Gene Jones, Spreading Rhythm Around: Black Popular Songwriters, 1880- 1920 (Routledge), 112-113.

18 Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birthing of the Recording Industry 1890-1919 (Routledge), 121.

19 Brooks, Lost Sounds, 269.

20 James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (Atheneum 1977), 123.

21 Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States (Oxford 1995), 105.

22 Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime (Oxford 1995), 116. [“Castles Dance Foxtrot: Call It Negro Step,” New York Herald, no date (Fall, 1914), clipping in the Castle Scrapbooks, Billy Rose Theater Collection, New York Public Library.]

23 Badger, A Life, 141.

24 Badger, A Life, 143.

25 Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birthing of the Recording Industry 1890-1919 (Routledge), 277.

26 Badger, A Life, 163.

27 James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (Atheneum), 235.

28 Badger, A Life, 193.

29 Badger, A Life, 217.

30 Badger, A Life, 217.

31 Badger, A Life, 219.

32 Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birthing of the Recording Industry 1890-1919 (Routledge), 291.