English

Spanish

From San Juan to San Juan Hill: The Experiences of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938) and Rogelio Ramirez (1913–1994)

De San Juan a San Juan Hill: Las experiencias de Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874-1938) y Rogelio Ramírez (1913-1994)

January 30, 2023

by Elena Martínez and Bobby Sanabria, Co-Artistic Directors of Bronx Music Heritage Center

The neighborhood of San Juan Hill in Manhattan is largely known for a few things: its connection to the area where Lincoln Center was built and the urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 60s; and one of the most famous musical theater works to be set against that history, West Side Story. Most people probably don’t even realize they are very familiar with the play’s music—everyone can hum along to “I Feel Pretty” or “America.” Musically, for those in the know, San Juan Hill will bring to mind Jazz due to its large African American demographic and the many musicians who made their home in the neighborhood, from Duke Ellington to Thelonious Monk. Referring back to West Side Story, there was also a small Puerto Rican enclave there (small demographically in relation to the Puerto Rican communities in other parts of the city, at various times, such as East Harlem or the South Bronx). In addition, two leading Afro-Puerto Rican figures lived in this west side neighborhood and, though separated by decades, they had something in common—each has been more associated with the African American community than with his Puerto Rican heritage.

How did the lives and legacies of Arturo Schomburg and Rogelio “Ram” Ramirez become associated with African Americans and not their Afro-Puerto Rican compatriots? Actually, early in the 20th century this wasn’t so strange a phenomenon; in that era, it was common for Afro-Puerto Ricans to settle in Black neighborhoods. The census data reveal that Afro-Puerto Ricans in New York City were more likely to marry African Americans than white-identified Puerto Ricans.1 They, like their Afro-Cuban compatriots, didn’t “leave their Spanish-Caribbean community behind, rather, they found acceptance and ease of living in already existing African diasporic spaces”.2 Though Afro-Latinos would have been familiar with these divisions along color lines, as racism was part of Caribbean culture, here in New York City they were exacerbated by U.S. society’s sharp racial divisions.

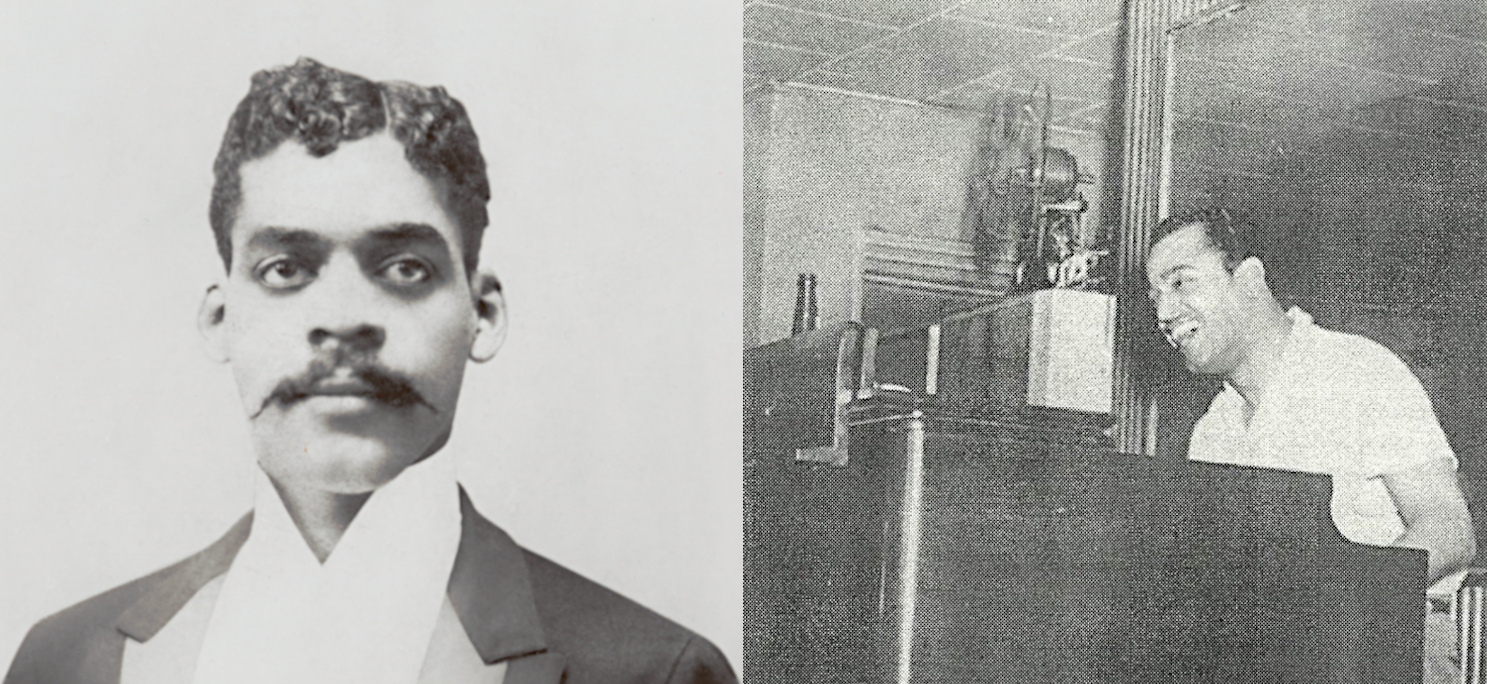

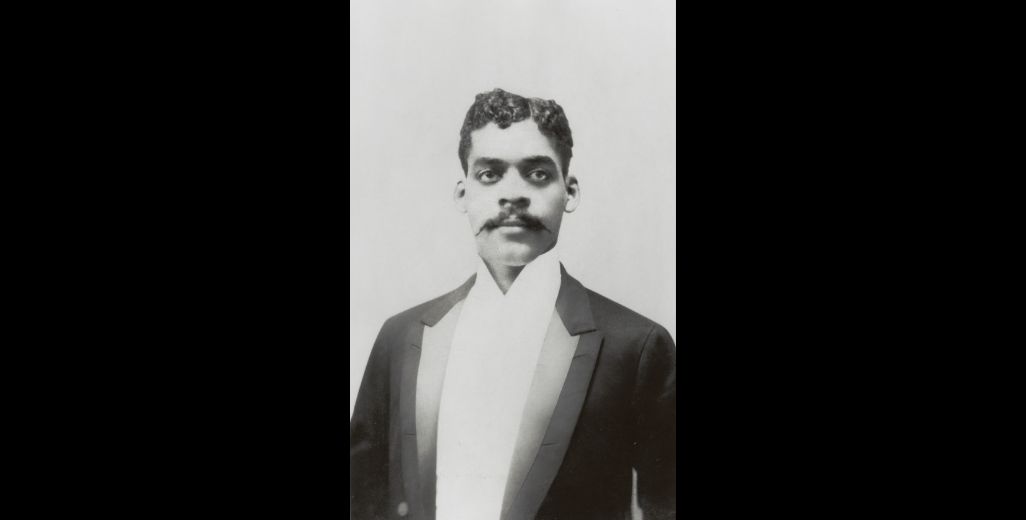

First there was Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, the book collector and archivist, who was of West Indian and German descent and born in Puerto Rico. He came to New York City as a young man of seventeen in 1891. He lived in lower Manhattan with Puerto Rican and Cuban nationalists; these two communities were very much engaged in the struggle to free themselves from Spanish rule, and New York City was a focal point for this struggle. Soon after, Arturo married Elizabeth Hatcher, an African American woman from Virginia, and they lived on West 62nd Street in the predominantly Black community of San Juan Hill. Though immersed in African American culture, he still retained ties to his Puerto Rican heritage and their alliance with the cause of Cuban independence from Spain. A personal recognition of this is seen in that his sons with Elizabeth were named after Cuban historical and revolutionary figures, Maximo Gomez and Kingsley Guarionex, and his later children were also given Spanish names.

El barrio de San Juan Hill, en Manhattan, es muy conocido por algunas cosas: su conexión con la zona en la que se construyó el Lincoln Center y los proyectos de renovación urbana de las décadas de 1950 y 1960; y una de las obras de teatro musical más famosas que se enmarca en esa historia, West Side Story. Probablemente, la mayoría de las personas ni siquiera se dan cuenta de que conocen la música de esta obra: todo el mundo puede tararear “I Feel Pretty” o “America”. Desde el punto de vista musical, a los entendidos en la materia, San Juan Hill les traerá a la mente el jazz, debido a su gran población afroamericana y a los numerosos músicos que tuvieron su hogar en el barrio, desde Duke Ellington hasta Thelonious Monk. Remitiéndonos a West Side Story, también había allí un pequeño enclave puertorriqueño (pequeño demográficamente en relación con las comunidades puertorriqueñas de otras partes de la ciudad, en diversas épocas, como East Harlem o el sur del Bronx). Además, en este barrio del oeste vivieron dos importantes figuras afro-puertorriqueñas que, aunque separadas por décadas, tenían algo en común: cada una de ellas ha estado más asociada a la comunidad afroamericana que a su herencia puertorriqueña.

¿Cómo se asociaron las vidas y los legados de Arturo Schomburg y Rogelio “Ram” Ramírez con los afroamericanos y no con sus compatriotas afro-puertorriqueños? En realidad, a principios del siglo XX esto no era un fenómeno tan extraño; en esa época, era común que los afro-puertorriqueños se asentaran en barrios negros. Los datos del censo revelan que los afro-puertorriqueños de la ciudad de Nueva York tenían más probabilidades de casarse con afroamericanos que los puertorriqueños de raza blanca.1 Al igual que sus compatriotas afrocubanos, no “abandonaron su comunidad hispano-caribeña, sino que encontraron aceptación y facilidad para vivir en los espacios de la diáspora africana ya existentes”.2 Aunque los afrolatinos estarían familiarizados con estas divisiones por colores, ya que el racismo formaba parte de la cultura caribeña, aquí en la ciudad de Nueva York se vieron exacerbadas por las marcadas divisiones raciales de la sociedad estadounidense.

Primero fue Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, coleccionista de libros y archivero, de ascendencia antillana y alemana, nacido en Puerto Rico. Llegó a Nueva York en 1891, siendo un joven de diecisiete años. Vivió en el bajo Manhattan con nacionalistas puertorriqueños y cubanos; estas dos comunidades estaban muy comprometidas en la lucha por liberarse del dominio español, y la ciudad de Nueva York era un punto de encuentro para esta lucha. Poco después, Arturo se casó con Elizabeth Hatcher, una mujer afroamericana de Virginia, y vivieron en West 62nd Street, en la comunidad predominantemente negra de San Juan Hill. Aunque estaba inmerso en la cultura afroamericana, seguía conservando los lazos con su herencia puertorriqueña y su alianza con la causa de la independencia cubana de España. Un reconocimiento personal de esto se ve en que sus hijos con Elizabeth recibieron nombres de figuras históricas y revolucionarias cubanas, Máximo Gómez y Kingsley Guarionex, y sus hijos posteriores también recibieron nombres en español.

Schomburg certainly would have been able to participate in that struggle while living in San Juan Hill. There were elements of the Cuban and Puerto Rican independence movements located not far from that neighborhood. The Club Borinquen, one of the many Puerto Rican organizations formed to fight for independence from Spain, was founded at a meeting on West 57th Street, just a few blocks from his residence. Dr. J. Julio Henna, another fighter in the struggle for independence, lived close by at 24 West 72nd Street.

Later, we see a shift in his politics when, in the first decade of the 20th century, Schomburg and his family relocated to Harlem. After the Spanish-Cuban-American War ended and Puerto Rico became a colony of the United States, Schomburg began to turn his interests from the independence movements to the concept of pan-Africanism and the global Black experience. In Harlem, he came into contact with people like activist Marcus Garvey and journalist John Edward Bruce and became part of a circle of Afro-Caribbean and African American intellectuals.

Schomburg is remembered specifically for his incredible collection of books, manuscripts and materials relating to Black history and culture. In 1926, the New York Public Library purchased this collection from Schomburg with a $10,000 grant from the Carnegie Foundation. It has become known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His collection has been a resource for important Black scholars of the Harlem Renaissance era such as W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and Claude McKay. Through his collection at the New York Public Library and its location in Harlem, it is often assumed that Schomburg was African American, and his Latino Spanish-speaking heritage is overlooked. This could be interpreted as an erasure of his heritage or Schomburg himself turning his back on it. However, all through his life, he identified himself as Afro-Latino. But he did see himself as part of a larger African diasporic community that connected the English and Spanish-speaking West Indies, as well as the U.S South.3

During the Harlem Renaissance, which spanned from post-WWI through the mid-1930s, Schomburg was embedded within the African American community culturally and politically. At this time, another young man arrived from Puerto Rico to settle in the San Juan Hill area. Rogelio Ramirez was born on September 15, 1913 in San Juan, Puerto Rico and arrived in New York City in 1920. He became known on the Jazz scene with the Anglicized version of his name, Roger, as well as the sobriquet “Ram,” the shortened, “hipified” nickname version for Ramirez. His songs are listed in the U.S. copyright office as written by Roger Ramirez.4

Sin duda, Schomburg pudo participar en esa lucha mientras vivía en San Juan Hill. Había elementos de los movimientos independentistas cubano y puertorriqueño situados a poca distancia de este barrio. El Club Borinquen, una de las muchas organizaciones puertorriqueñas formadas para luchar por la independencia de España, se fundó en una reunión en West 57th Street, a pocas manzanas de su residencia. El Dr. J. Julio Henna, otro luchador por la independencia, vivía cerca, en el número 24 de West 72nd Street.

Más tarde, vemos un cambio en su política cuando, en la primera década del siglo XX, Schomburg y su familia se trasladan a Harlem. Una vez finalizada la guerra hispano-cubana-estadounidense y cuando Puerto Rico se convirtió en una colonia de los Estados Unidos, Schomburg comenzó a desviar sus intereses de los movimientos independentistas hacia el concepto de panafricanismo y la experiencia global de los negros. En Harlem, entró en contacto con personas como el activista Marcus Garvey y el periodista John Edward Bruce, y pasó a formar parte de un círculo de intelectuales afrocaribeños y afroamericanos.

Schomburg es recordado específicamente por su increíble colección de libros, manuscritos y materiales relacionados con la historia y la cultura negras. En 1926, la Biblioteca Pública de Nueva York compró esta colección a Schomburg con una subvención de $10,000 de la Carnegie Foundation. Se conoce como el Centro Schomburg para la Investigación de la Cultura Negra. Su colección ha sido un recurso para importantes estudiosos negros de la época del Renacimiento de Harlem, como W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes y Claude McKay. Debido a su colección en la Biblioteca Pública de Nueva York y a su ubicación en Harlem, a menudo se supone que Schomburg era afroamericano, y se pasa por alto su herencia latina de habla hispana. Esto podría interpretarse como un olvido de su herencia o como si el propio Schomburg le diera la espalda. Sin embargo, durante toda su vida se identificó como afrolatino. Sin embargo, se consideraba parte de una comunidad de la diáspora africana más amplia que conectaba las Indias Occidentales de habla inglesa e hispana, así como el sur de los Estados Unidos.3

Durante el Renacimiento de Harlem, que abarcó desde después de la Primera Guerra Mundial hasta mediados de la década de 1930, Schomburg se integró en la comunidad afroamericana cultural y políticamente. En esta época, otro joven llegó de Puerto Rico para instalarse en la zona de San Juan Hill. Rogelio Ramírez nació el 15 de septiembre de 1913 en San Juan de Puerto Rico y llegó a la ciudad de Nueva York en 1920. Se hizo conocido en la escena del jazz con la versión inglesa de su nombre, Roger, así como con el sobrenombre “Ram”, la versión abreviada y “hipificada” del apodo de Ramírez. Sus canciones figuran en la oficina de derechos de autor de los Estados Unidos como escritas por Roger Ramírez.4

By the early age of thirteen he was already a member of the musician’s union.5 Ramirez became a Jazz pianist later known for playing in the swing style of the 1930s and the progressive bop style of the 1940s. During the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Ramirez played with the Louisiana Stompers in 1930 and Blues singer Monette Moore in 1933. Moore was a Blues vocalist who had performed with Fats Waller, and she became one of Ramirez’s primary influences. In 1934, he worked with Duke Ellington’s small group, which was led by cornetist Rex Stewart and recorded with that band.6 The decade also saw him perform with drummer “Big” Sid Catlett, vocalist and “Mayor of Harlem” Willie Bryant, and trumpeter Bobby Martin. By the end of the 1930s, he performed with virtuosic drummer Chick Webb’s orchestra when vocalist Ella Fitzgerald and trumpeter Mario Bauzá were in the band.

But when it comes to Jazz music, Ramirez is largely remembered for being one of the co-composers in 1941 of the song “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” along with Jimmy Davis and James Sherman. Ramirez was the composer of the melody and harmony; Davis wrote the lyrics. Although originally written exclusively for the legendary vocalist Billie Holiday, due to a recording ban at the time, she didn’t record the song until 1945. It immediately became popular not only with the public, but with musicians. Luminaries like alto saxophone virtuoso Charlie Parker put his unique stamp on the piece, and it has since been interpreted by many artists including Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn (backed by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie), Sonny Stitt, and even pop vocalists such as Barbara Streisand, Patty LaBelle and Whitney Houston. But it is the original version recorded by Holiday with whom it is most associated. Her recorded interpretation of the piece has the unique distinction of having been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1989.

This was a very active period for Latino musicians in the Jazz scene. Trombonist Fernando Arbello who had been in Fletcher Henderson’s band in the 1920s joined Mario Bauzá in Chick Webb’s orchestra in 1937. Trumpeter Miguel Angel Duchesne performed with Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, and trumpeter Louis “King” Garcia performed with Benny Goodman and the Dorsey Brothers. Mariano Barreto—the brother of Don Azpiazu who led the Cuban music craze in New York City—played with vocalist Noble Sissle’s band while they were in Europe.7 It’s not surprising that Ramirez fit right into this scene as a pianist, and later, an organist. Like several Latin musicians during this time period, he had been absorbed by Harlem’s exploding music scene and played exclusively as a Jazz musician, never venturing into playing any type of Latin music.

Latin musicians who played Jazz straddled a hard line—and continue to do so. They were either ghettoized as Salsa or Latin Jazz musicians only (e.g. Tito Puente), or if they were part of the mainstream Jazz canon, like Ramirez, their Latino cultural heritage was ignored. In fact, as was the case with Ramirez, they were treated as a footnote or completely erased from the written Jazz historical record. There is a long history of this type of omission, lack of recognition, and for the most part, erasure of the contributions of Latino musicians to Jazz. Take for instance, the three critically acclaimed tomes on Jazz history written by the noted author and Jazz historian Scott Yanow, Classic Jazz, Swing, and Bebop. In all three books, there is absolutely no mention of Ramirez. This is despite the fact that Ramirez had the extensive resume mentioned above, and that he was the co-composer of one of the genre’s most iconic compositions. Meanwhile, lesser known players, composers, arrangers, and bandleaders, who played only minor roles in Jazz history, are mentioned in all three books.

Ramirez and his importance to the co-creation of “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” is rarely mentioned or is completely missing from the historical Jazz canon. Why? Scholar and musician Chris Washburne in his critically acclaimed book, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, opens the door for the reason for this erasure: “…the Caribbean and Latin American presence in Jazz history complicates the black/white dichotomy, racial politics in the U.S. Jazz scene”.8 In this climate, there is no room for the recognition of the Latino presence in Jazz for musicians like Ramirez and “these decisions artificially collapse culture into simplistic racial categories”.9 This lack of recognition manifests itself in Jazz’s written history, amongst the musicians,10 and in the mainstream world—as in Ken Burns’ eighteen-hour documentary series on Jazz, which totally neglected the contributions of Latinos to Jazz history. Ramirez co-composed a song that has become legendary among Jazz musicians, as part of the genre, and with fans of the music, yet he is little known in history.

Following “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” in 1941, Ramirez continued to work exclusively in New York City’s Jazz scene. In the 1950s, he formed his own trio and began to play organ, while continuing his role as an in-demand pianist. The next few decades were very productive for him as he recorded his own albums and appeared on others as a sought-after sideman. In 1980, he performed at Carnegie Hall as a featured artist for the solo piano series spotlight of George Wein’s Kool Jazz Fest. At the same time, he was a member of the Harlem Blues and Jazz Band, which toured throughout Germany. The band included many Jazz musicians like himself who had played in the 1920s and 30s during what became known as “The Jazz Era.” In 1968, he toured Europe with Blues legend T-Bone Walker and continued to freelance. Ramirez passed away due to kidney failure in Queens, New York on January 11, 1994 in obscurity. Despite his cultural significance, most of New York’s City’s Latino community did not know of his historical importance to Jazz, let alone that he was Puerto Rican.

Arturo Schomburg and Ram Ramirez are two Puerto Rican pioneers in the fields of literature and Jazz who have become iconic figures in the history of Black culture in New York City. Due to the nature of racial politics in the U.S., their associations, and their fields of work, these two men have become more identified with the African American community than with their native Puerto Rico. The complexity of their cultural backgrounds became invisible. Though Schomburg is readily remembered, because of the major institution that bears his name, Ramirez doesn’t have this benefit. That they once made their homes in San Juan Hill is a testimony to the importance of the neighborhood to the history of not only the city’s African American community, but its Puerto Rican community as well.

Con tan solo trece años ya era miembro del sindicato de músicos.5 Ramírez se convirtió en un pianista de jazz conocido posteriormente por tocar en el estilo swing de la década de 1930 y en el estilo bop progresivo de la década de 1940. Durante el apogeo del Renacimiento de Harlem, Ramírez tocó con los Louisiana Stompers en 1930 y con la cantante de Blues Monette Moore en 1933. Moore era una vocalista de Blues que había actuado con Fats Waller, y se convirtió en una de las principales influencias de Ramírez. En 1934, trabajó con la pequeña agrupación de Duke Ellington, dirigida por el cornetista Rex Stewart, y grabó con esa banda.6 En esta década también actuó con el baterista “Big” Sid Catlett, el vocalista y “alcalde de Harlem” Willie Bryant, y el trompetista Bobby Martin. A finales de la década de 1930, actuó con la orquesta del virtuoso baterista Chick Webb cuando la vocalista Ella Fitzgerald y el trompetista Mario Bauzá estaban en la banda.

Pero en lo que respecta a la música de jazz, Ramírez es recordado sobre todo por ser uno de los co-compositores en 1941 de la canción “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” junto con Jimmy Davis y James Sherman. Ramírez fue el compositor de la melodía y la armonía; Davis escribió la letra. Aunque originalmente fue escrita en exclusiva para la legendaria vocalista Billie Holiday, debido a una prohibición de grabación de la época, ella no grabó la canción hasta 1945. La canción se hizo inmediatamente popular no solo entre el público, sino también entre los músicos. Luminarias como el virtuoso saxofonista alto Charlie Parker pusieron su sello único en la pieza, y desde entonces ha sido interpretada por muchos artistas, como Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn (acompañada por Charlie Parker y Dizzy Gillespie), Sonny Stitt, e incluso vocalistas pop como Barbara Streisand, Patty LaBelle y Whitney Houston. Pero es la versión original grabada por Holiday la que más se recuerda. Su interpretación grabada de la pieza tiene la distinción única de haber sido incluida en el Salón de la Fama de los Grammy en 1989.

Este fue un período muy activo para los músicos latinos en la escena del jazz. El trombonista Fernando Arbello, que había estado en la banda de Fletcher Henderson en la década de 1920, se unió a Mario Bauzá en la orquesta de Chick Webb en 1937. El trompetista Miguel Ángel Duchesne actuó con la orquesta de Paul Whiteman, y el trompetista Louis “King” García actuó con Benny Goodman y los Dorsey Brothers. Mariano Barreto -el hermano de Don Azpiazu, que lideró la moda de la música cubana en la ciudad de Nueva York- tocó con la banda del vocalista Noble Sissle durante su estancia en Europa.7 No es de extrañar que Ramírez encajara perfectamente en esta escena como pianista y, más tarde, como organista. Al igual que varios músicos latinos de esta época, había sido absorbido por la escena musical en auge de Harlem y tocaba exclusivamente como músico de jazz, sin arriesgarse a tocar ningún tipo de música latina.

Los músicos latinos que tocaban jazz se encontraban en una situación difícil, y aún hoy lo están. O bien se les clasificaba en un gueto como músicos de salsa o de jazz latino (por ejemplo, Tito Puente), o bien, si formaban parte del canon del jazz convencional, como Ramírez, se ignoraba su herencia cultural latina. De hecho, como en el caso de Ramírez, se les trató como una nota a pie de página o se les borró por completo del registro histórico del jazz escrito. Hay una larga historia de este tipo de omisiones, falta de reconocimiento y, en su mayor parte, borrado de las contribuciones de los músicos latinos al jazz. Tomemos como ejemplo los tres tomos aclamados por la crítica sobre la historia del jazz escritos por el conocido autor e historiador del jazz Scott Yanow, Classic Jazz, Swing y Bebop. En los tres libros no se menciona en absoluto a Ramírez. Todo ello a pesar de que Ramírez contaba con el extenso currículum antes mencionado, y que fue el co-compositor de una de las composiciones más icónicas del género. Mientras tanto, en los tres libros se menciona a músicos, compositores, arreglistas y directores de banda menos conocidos, que desempeñaron un papel menor en la historia del jazz.

Ramírez y su importancia en la cocreación de “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” rara vez se menciona o está completamente ausente del canon histórico del jazz. ¿Por qué? El académico y músico Chris Washburne, en su libro aclamado por la crítica, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, explica la razón de este ocultamiento: “…la presencia caribeña y latinoamericana en la historia del jazz complica la dicotomía blanco/negro, la política racial en la escena del jazz estadounidense”.8 En este clima, no hay lugar para el reconocimiento de la presencia latina en el jazz para músicos como Ramírez y “estas decisiones colapsan artificialmente la cultura en categorías raciales simplistas”.9 Esta falta de reconocimiento se manifiesta en la historia escrita del jazz, entre los músicos,10 y en el mundo mainstream -como en la serie documental de dieciocho horas de Ken Burns sobre el jazz, que descuidó totalmente las contribuciones de los latinos a la historia del jazz. Ramírez compuso una canción que se ha hecho legendaria entre los músicos de jazz, como parte del género, y entre los aficionados a la música, y sin embargo es poco conocido en la historia.

Después de “Loverman (Oh, Where Can You Be?)” en 1941, Ramírez continuó trabajando exclusivamente en la escena del jazz de Nueva York. En la década de 1950, formó su propio trío y comenzó a tocar el órgano, al tiempo que continuaba con su rol de pianista muy solicitado. Las siguientes décadas fueron muy productivas para él, ya que grabó sus propios álbumes y apareció en otros como un codiciado acompañante. En 1980, actuó en el Carnegie Hall como artista principal en la serie de pianos solistas del Kool Jazz Fest de George Wein. Al mismo tiempo, fue miembro de la Harlem Blues and Jazz Band, que realizó una gira por toda Alemania. La banda incluía a muchos músicos de jazz como él que habían tocado en las décadas de 1920 y 1930 durante lo que se conoció como “La Era del Jazz”. En 1968, realizó una gira por Europa con la leyenda del blues T-Bone Walker y continuó trabajando por cuenta propia. Ramírez falleció a causa de una insuficiencia renal en Queens, Nueva York, el 11 de enero de 1994 en la oscuridad. A pesar de su importancia cultural, la mayor parte de la comunidad latina de la ciudad de Nueva York no conocía su importancia histórica para el jazz, y mucho menos que era puertorriqueño.

Arturo Schomburg y Ram Ramírez son dos pioneros puertorriqueños en los campos de la literatura y el jazz que se han convertido en figuras icónicas de la historia de la cultura negra en la ciudad de Nueva York. Debido a la naturaleza de la política racial en los Estados Unidos, sus asociaciones y sus campos de trabajo, estos dos hombres se han identificado más con la comunidad afroamericana que con su Puerto Rico natal. La complejidad de sus orígenes culturales se hizo invisible. Si bien se recuerda fácilmente a Schomburg, debido a la importante institución que lleva su nombre, Ramírez no tiene esta ventaja. El hecho de que alguna vez tuvieran su hogar en San Juan Hill es un testimonio de la importancia del barrio para la historia no solo de la comunidad afroamericana de la ciudad, sino también de su comunidad puertorriqueña.

Footnotes

1 Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The World of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg,” pg. 83. In The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States. Ed. Miriam Jimenez Roman and Juan Flores. Duke University Press, Durham. 2020.

2 Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, pg. 9. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

3 Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, pgs. 4–5. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

4 Tomas Pena, “Boricua Jazz Pioneer: Roger “Ram” Ramirez (1913-1994).”

https://jazzdelapena.com/puerto-rico-project/boricua-jazz-project-pioneer-roger-ram-ramirez-1913-1994/

5 Basilio Serrano, Juan Tizol: His Caravan Through American Life & Culture, pg. 271. Xlibris Corporation. 2012.

6 Tomas Pena, “Boricua Jazz Pioneer: Roger “Ram” Ramirez (1913-1994).”

https://jazzdelapena.com/puerto-rico-project/boricua-jazz-project-pioneer-roger-ram-ramirez-1913-1994/

7 John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions 1880s to Today, pg. 83. Schirmer Books, New York. 1999.

8 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, pg. 136. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

9 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, pg. 96. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

10 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, pg. 53. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

References

Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The Migrations of Arturo Schomburg: On Being Antillano, Negro and Puerto Rican in New York 1891-1938.” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 21, #1, pg. 3-47, Fall 2001.

Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The World of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg,” pgs. 70-91. In The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States. Ed. Miriam Jimenez Roman and Juan Flores. Duke University Press, Durham. 2020.

John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions 1880s to Today. Schirmer Books, New York. 1999.

Basilio Serrano, Juan Tizol: His Caravan Through American Life & Culture. Xlibris Corporation. 2012.

Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

Notas al pie de página

1 Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The World of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg”, p. 83. En The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States. Ed. Miriam Jiménez Román y Juan Flores. Duke University Press, Durham. 2020.

2 Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, p. 9. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

3 Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, p. 4–5. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

4 Tomas Pena, “Boricua Jazz Pioneer: Roger “Ram” Ramirez (1913-1994).” https://jazzdelapena.com/puerto-rico-project/boricua-jazz-project-pioneer-roger-ram-ramirez-1913-1994/

5 Basilio Serrano, Juan Tizol: His Caravan Through American Life & Culture, p. 271. Xlibris Corporation. 2012.

6 Tomas Pena, “Boricua Jazz Pioneer: Roger “Ram” Ramirez (1913-1994). https://jazzdelapena.com/puerto-rico-project/boricua-jazz-project-pioneer-roger-ram-ramirez-1913-1994/

7 John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions 1880s to Today, p. 83. Schirmer Books, New York. 1999.

8 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, p. 136. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

9 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, p. 96. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

10 Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz, p. 53. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

Referencias

Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The Migrations of Arturo Schomburg: On Being Antillano, Negro and Puerto Rican in New York 1891-1938.” Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 21, #1, p. 3-47, otoño de 2001.

Chris Washburne, Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz. Oxford University Press, New York, 2020.

Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, “The World of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg,” p. 70-91. En The Afro-Latin@ Reader: History and Culture in the United States. Ed. Miriam Jimenez Roman y Juan Flores. Duke University Press, Durham. 2020.

John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions 1880s to Today. Schirmer Books, New York. 1999.

Basilio Serrano, Juan Tizol: His Caravan Through American Life & Culture. Xlibris Corporation. 2012.

Vanessa K. Valdes. Diasporic Blackness: The Life and Times of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. University of New York Press, Albany. 2017.

If you have questions about the media featured on this site, please email [email protected].

Top image courtesy of: The New York Public Library

Si tiene preguntas sobre los medios que aparecen en este sitio, envíe un correo electrónico a [email protected].

Traducido al español por GoDiversity.com.

Imagen superior por cortesía de: The New York Public Library