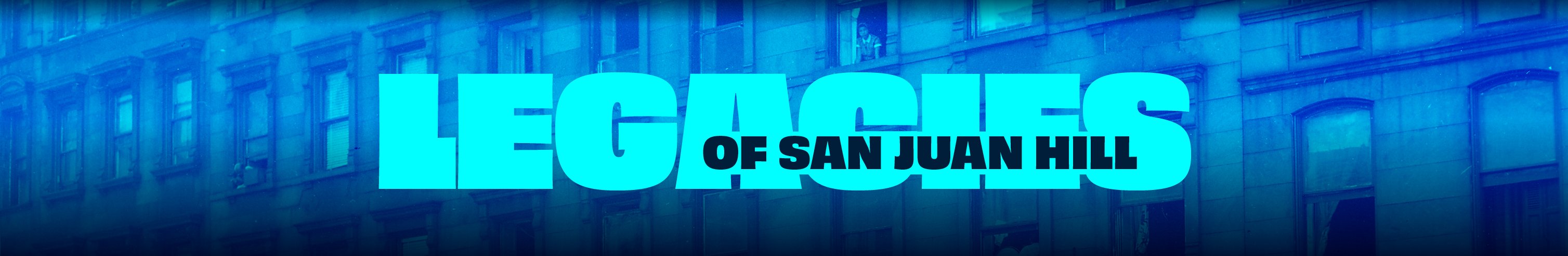

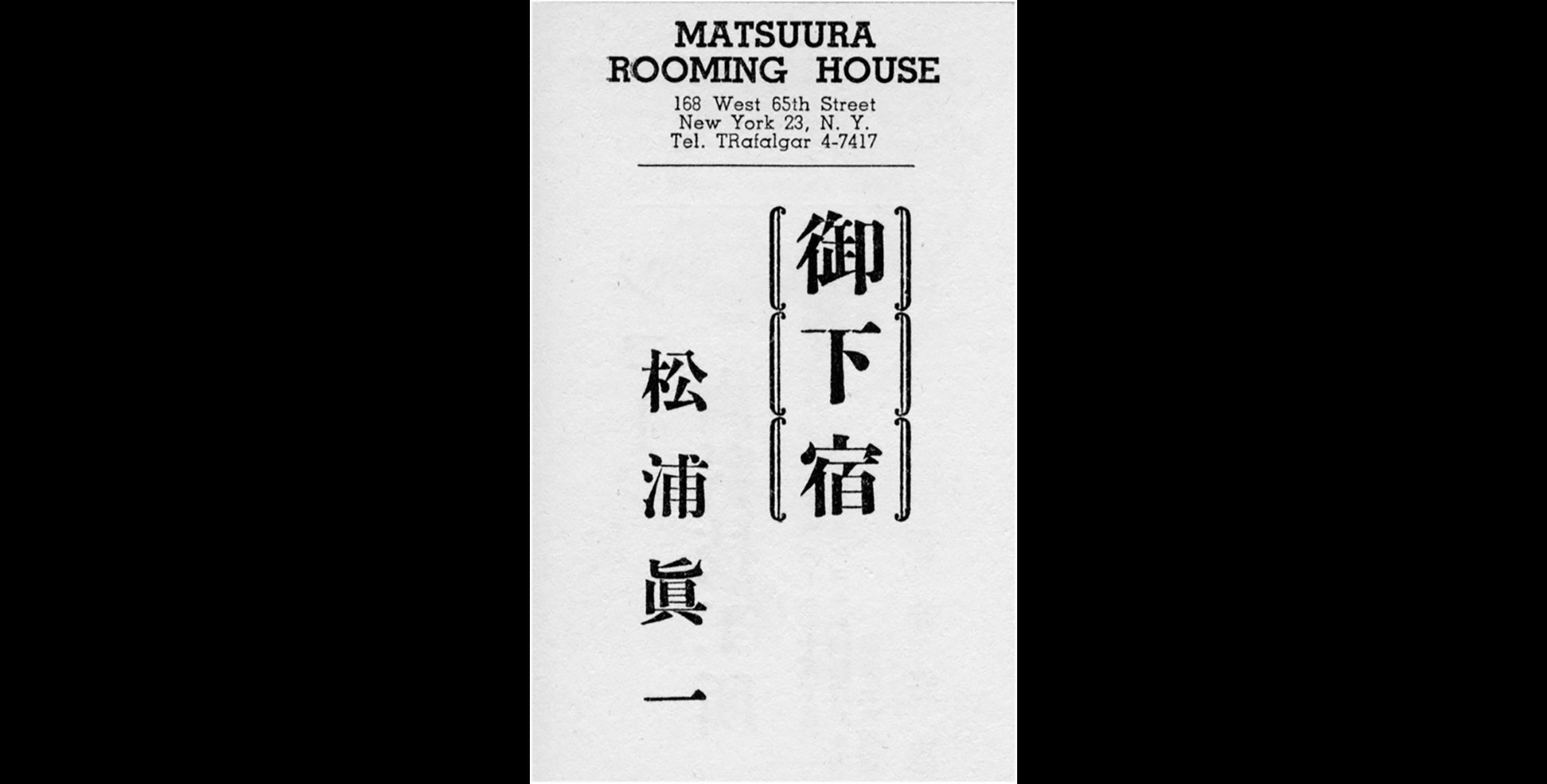

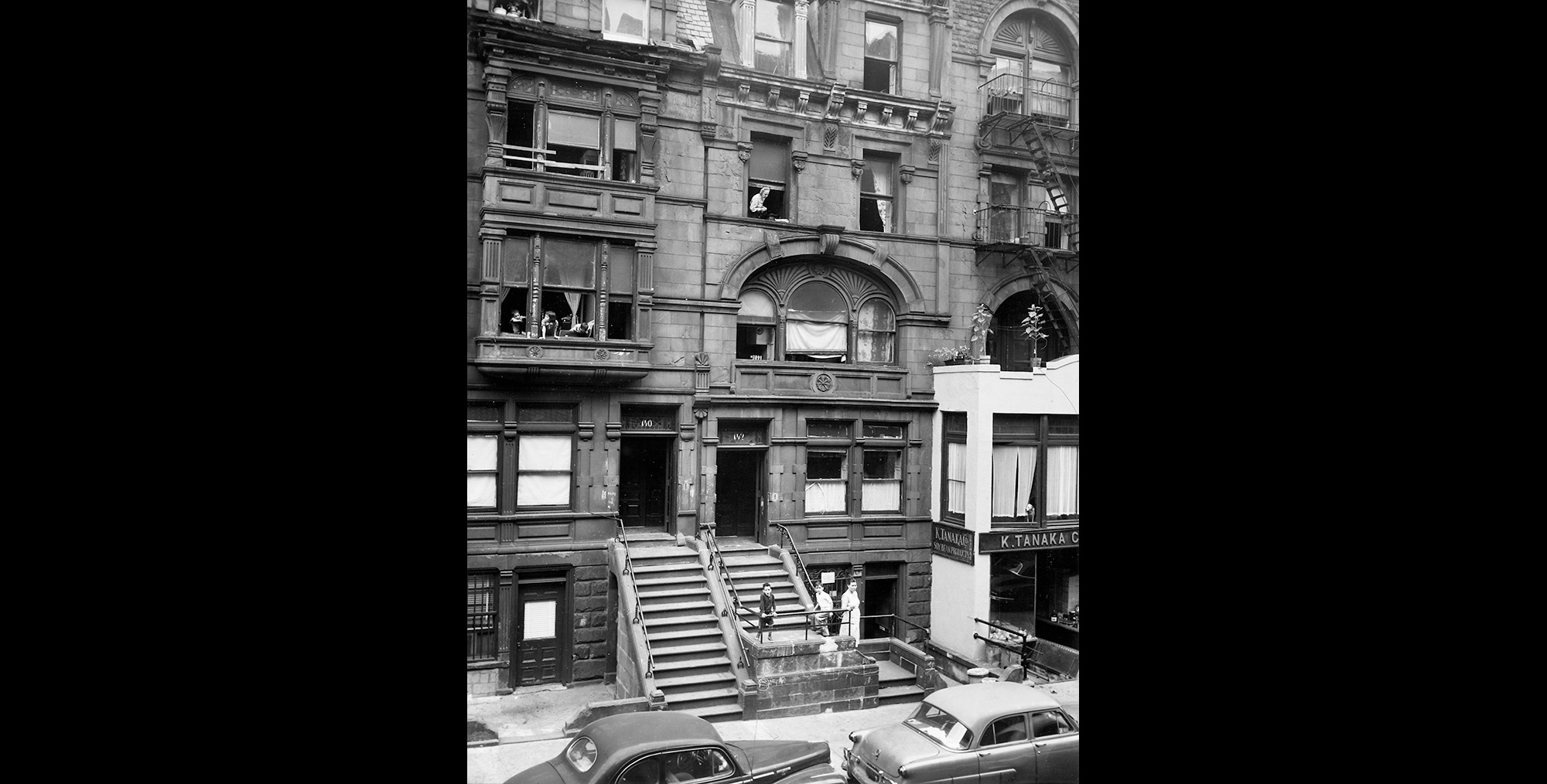

West 65th Street, Lincoln Square, 1956. K. Tanaka grocery store pictured.

New York City Parks Photo Archive

Japanese Americans in San Juan Hill

Japanese Americans in San Juan Hill

February 11, 2025

by Greg Robinson, Professor at l’Université du Québec à Montréal

The history of Japanese Americans in the San Juan Hill area reflects the distinctive and wide-ranging history of ethnic Japanese in New York across the first half of the 20th century. From the start, New York’s Japanese population was notable for its diversity, economic and cultural vitality, and artistic production. Without losing these essential qualities, it would be dramatically reshaped in the World War II era.

The first Japanese immigrants arrived in the New York area during the late 1800s. By 1920 the local Japanese population had reached a total of approximately 5,000–6,000 people. New York housed the only sizeable Japanese American community east of the Rocky Mountains, and one completely different from those on the West Coast and Hawaii.1

To begin with, Japanese communities in the Pacific region were largely rural, and urban populations there were largely relegated to segregated enclaves by poverty and racial discrimination. Japanese-white marriages were rare and mostly illegal, Japanese communities centered on nuclear family groups, and by 1924 the total Issei (immigrant) population had been surpassed in number by their Nisei children (native-born citizens).

In contrast, the Big Apple’s Japanese population remained largely adult, immigrant and male—with a sizeable fraction of these men taking non-Japanese partners. The Nisei who settled in New York generally did so as adults, and were not the children of the people already there. New York had no single Japantown. Ethnic Japanese, unhampered by prejudice, scattered across the city, and even into nearby suburbs.

Furthermore, unlike on the Pacific rim, where most ethnic Japanese worked in the produce or fishing industries, the Big Apple’s Japanese population was comprised of businessmen and office workers (many working for American branches of Japanese-owned firms), doctors and other professionals, clergy and industrial laborers—notably shipyard workers. The community boasted cosmopolitan circles of intellectuals and activists, and was notable for its visual and performing artists, including outstanding figures such as painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, sculptor Isamu Noguchi, and star musicians Yoichi Hiraoka and Hizi Koyke (and for a few years, actor Sessue Hayakawa). Japanese students and employees were a visible presence at Columbia University. Most importantly, as we shall see more presently, a good part of the Japanese population found work as domestic laborers.

It is not clear precisely when the first Japanese Americans moved to the San Juan Hill area. The 1910 U.S. census listed dozens of domestics working in private homes in the vicinity of Columbus Circle and on Central Park West. There were also some young professionals in the area. Rokuro Koharu, a doctor who had an apartment at 40 West 64th Street, ran a clinic next door at No. 42. Kenshi Takaguchi, an office worker, lived nearby at 1931 Broadway. Bunzo Inouye, a draftsman, rented a room at 108 West 61st Street. Henry Imamura, a cotton agent, lodged with a white couple at 27 West 61st Street.

The main center of Japanese residence in the area before World War I was a boardinghouse located at 121 West 64th Street. There were Japanese lodgers there as early as 1904, and people signing themselves “K.O.” and “Karnay” and “Yoshino” all posted advertisements for domestic work with that contact address. The 1910 census lists at that address a boardinghouse managed by John Yamamoto. It housed seven Japanese lodgers, all of them also boardinghouse workers, apart from Robert Kimura, a lawyer.

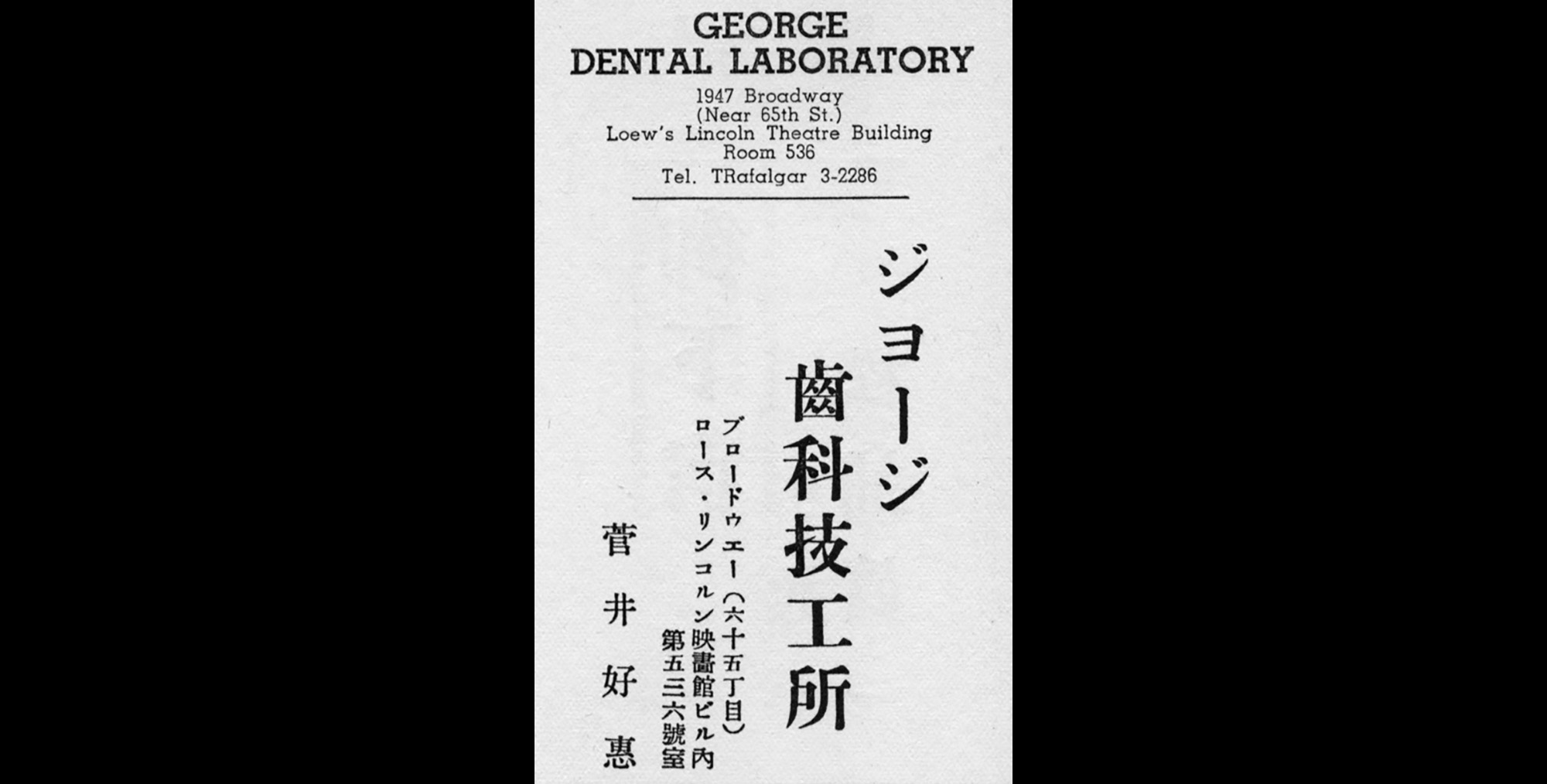

During this period, Japanese businesses also migrated to the area. In 1910 the Miyako, New York’s first high-end Japanese restaurant, opened in a brownstone at 340 West 58th Street, at the borders of the district. By mid-1919, when the bilingual English-Japanese newspaper Nichibei Jiho (Japanese American Commercial Weekly) published a citywide Japanese business directory, several of the shops and services listed were located in the area. These included the Suigetsudo confectionary shop at 161 W. 71st Street and the Shofuken Confectionery at 166 West 58th Street; the Circle (also known as Nakamura) Barber Shop at 22 West 60th Street; The Japanese Help Supply Agency, an employment agency, at 68 West 58th Street; and the medical offices of Dr. E.E. Yoshi on West 71st Street. Yoshi would go on to share offices for a time with another Japanese physician, Dr. Kenichi Iwamoto. Dr. M. Tsuchiya, a dentist, would also practice in the area.

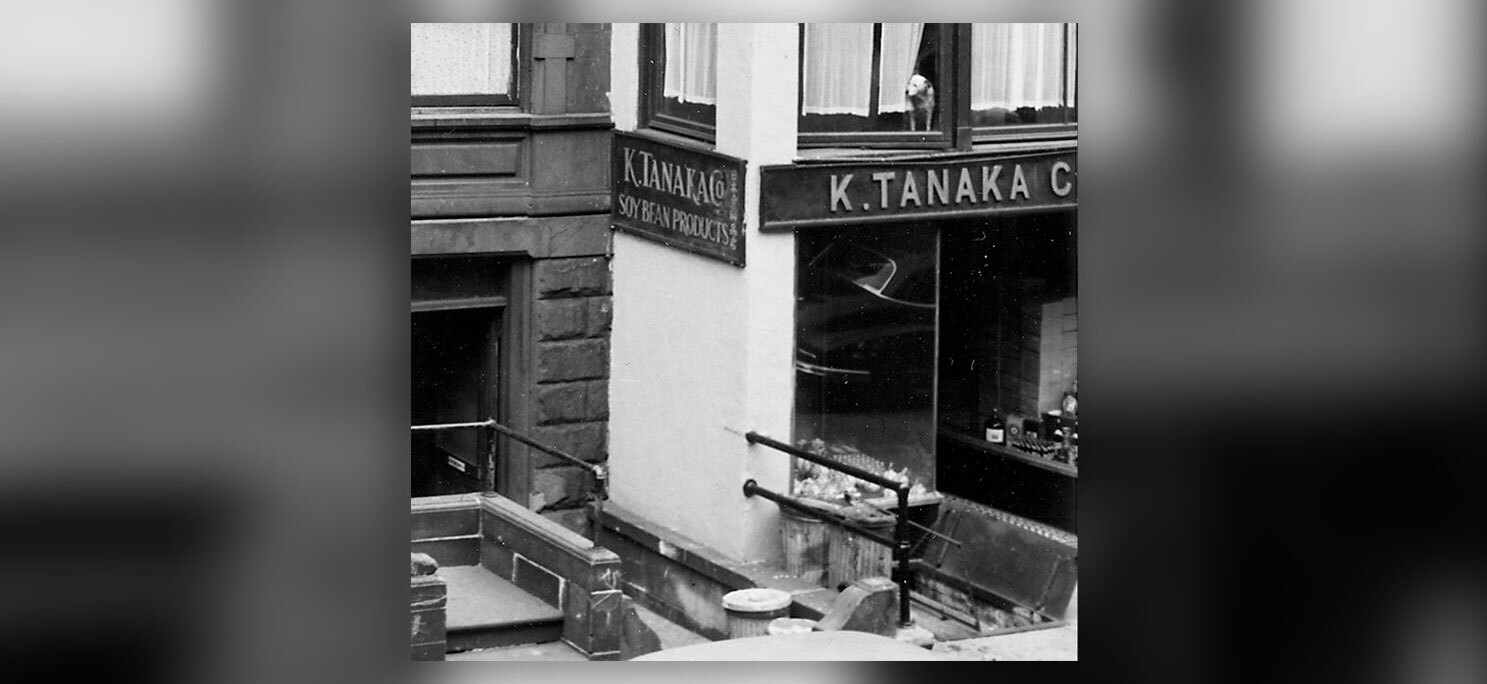

As before the First World War, boarding houses remained the center of community residence. The Nichibei Jiho directory listed the Young Man’s Boarding House at 23 West 60th Street and Mrs. Mukai’s nearby at 26 West 60th Street. Other sources mention a rooming house managed by Yoshitozu and Zambi Aizawa within a larger building at 17 W. 63rd Street. Most importantly, there was a row of boarding houses on West 65th Street. Toru Takeuichi and his wife ran the Ichiriki Boarding House (later known as Empire Hotel) at No. 146 while Ryuchi Murikami and his wife headed the Taiyo at 148 W. 65th. Later on, the Matsuura Rooming House opened at 168 W. 65th.2

Who lived in these boardinghouses, and what work did they do? Surviving sources of information are spotty. Census returns for 1930 and 1940, supplemented by “situations wanted” announcements for domestics in newspapers such as The New York Times, indicate that the boarders were generally single males, of an average of about 40 years of age. They worked as cooks and waiters in restaurants, or as butlers, valets, cooks, maids, houseworkers or chauffeurs for white families. (Other Japanese domestics in the area lived with the white families they served). Occasionally a husband-and-wife team would advertise their joint services. Some boarders would leave for the countryside in summertime and work at resorts.

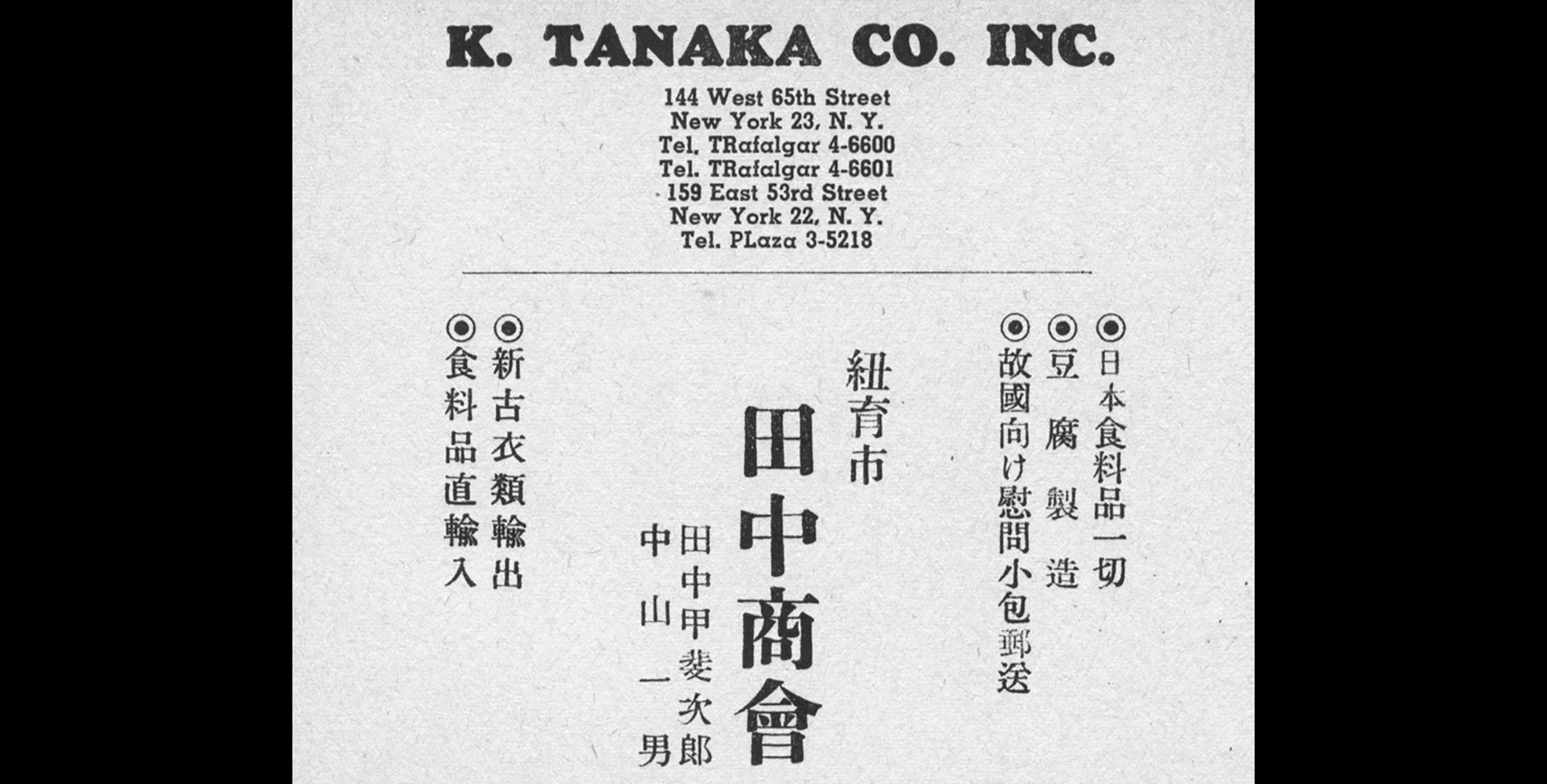

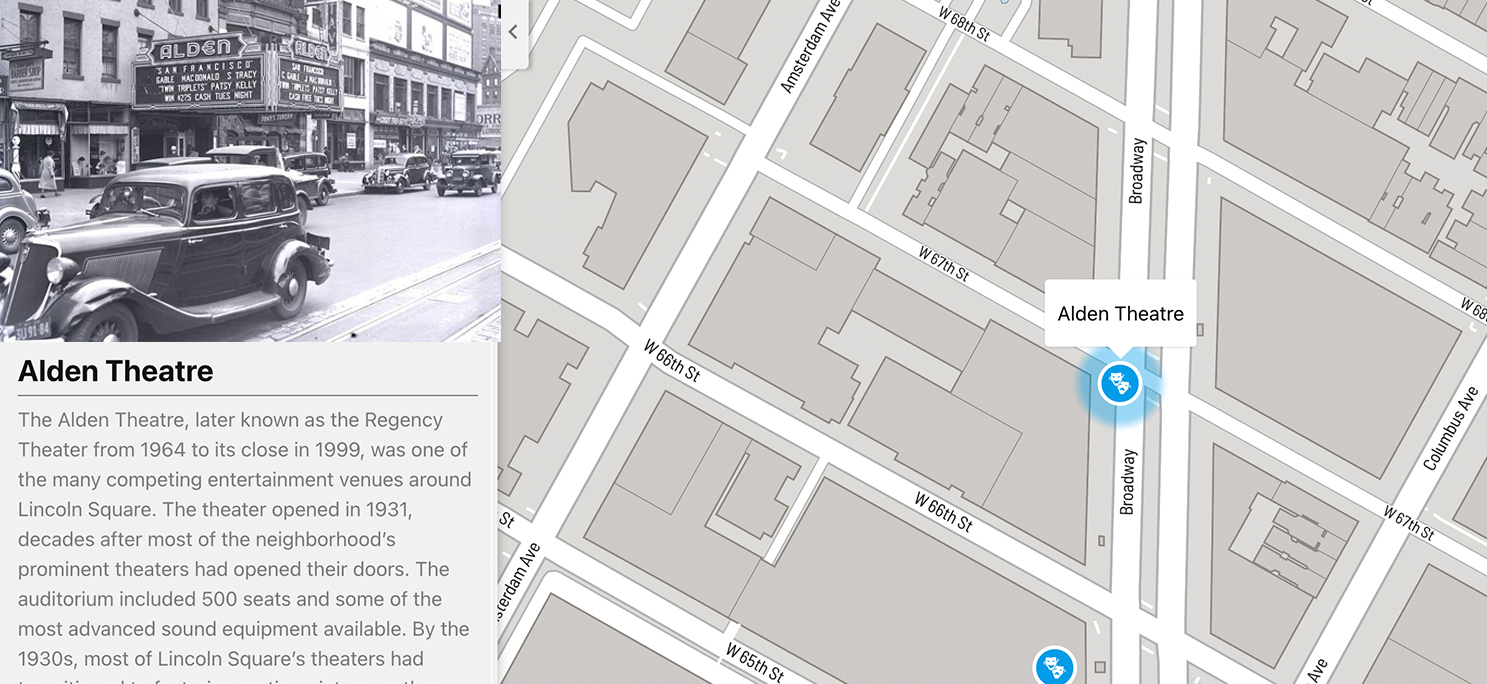

Once the boardinghouses were established, businesses came to serve (and sometimes employ) their residents. Taiyo housed a small Japanese restaurant on its ground floor. Shioya Auto Taxi was at 148 West 65th St. In 1926, Dr. Kuro Murase established a Japanese grocery store called Japan Provisions Company at 150 (later 144) West 65th Street. Others followed, including K. Tanaka’s Japan Products shop. There were also leisure activities. A Japanese basketball league played its games at the High School of Commerce on West 65th Street. A surviving Japanese American directory from 1939 lists a Nippon Archery Club at 243 West 68th Street.

In 1930 Japanese culture gained new visibility in the local landscape when Reverend Sokei-An Shigetsu Sasaki opened the Ryomo Zen Buddhism Institute (also known as Buddhist Society of America) at 63 West 70th Street. Sasaki was a poet, novelist, painter, and sculptor as well as a Buddhist monk. In 1932, the Nichibei Jiho reported that Reverend Sasaki was holding services every Wednesday and Saturday evening at 8 o’clock. “His lectures are given in English, and he extends his invitation to any one interested in Buddhism.” As a result, his lectures were attended by many non-Japanese. In 1937 Reverend Hosen Seki came to New York and established an office at 144 W. 65th Street. with the goal of creating a Japanese-language institution to serve local Buddhists. In 1938 he founded the New York Buddhist Church on West 94th Street.

The San Juan Hill Japanese enclave was physically unprepossessing, at least compared with Chinatown. In 1934 columnist Helen Worden noted, “New York's Japanese section Is very small. It centers around the middle upper West Side….the Japan Products Company at 144 West 65th Street [sells] water chestnuts and bamboo sprouts. Strangely enough, the Chinese have retained their character. The Japanese, however, have taken on the ways and manners of the Occidentals. On Doyers, Pell and Mott Streets, you will see curious Chinese temple-shaped roofs, strange hieroglyphic-like signs In the windows, hear the sound of joss house calls and smell the temple incense. On West 65th Street is nothing more than a row of conventional down-at-the-heels brownstone front houses to guide you to the land of Nippon.”

All the same, the neighborhood was not devoid of moments of excitement. In February 1920, the New York Evening World reported that twenty-four Japanese men had been arrested at 146 West 65th Street. When they confessed to shooting craps, presiding Magistrate Levine declared that the Japanese had as much right as anyone else to play the national game in the sanctity of a private house, and released the suspects. In 1935 the Brooklyn Eagle told the sad story of George Keneko, an unemployed chauffeur upset over the absence of his white wife Esther, who was working at the Queens mansion of the wealthy banker Tokunuski Shima. Keneko went out to the Shima house in a jealous rage, attempted to kill his wife, then committed suicide there.

World War II drastically altered New York’s Japanese community. Even before the outbreak of war, heightened international tensions prompted the city's Japan-owned business firms to begin closing their doors, and their employees returned to Japan. By the time of World War II, the city’s Japanese population had shrunk to less than half its prewar height. Community unemployment rose to such levels that in September 1941 local groups held a Nisei job conference at the Westside YMCA on West 63rd street to address the situation. Following Pearl Harbor, the Japanese consulate and remaining Japanese businesses (including an office at Columbus Circle maintained by the Japanese Army) were shuttered by the American government. Japanese immigrants all became “enemy aliens” and were thereby subjected to a curfew and limits on banking and travel. Dozens of community leaders were arrested and detained at Ellis Island.

The San Juan Hill community was especially vulnerable. As Japanese restaurants and shops shut their doors, and domestics working for white families were subjected to racist firings, the population faced mass unemployment. There was ambient harassment, official and unofficial. In early 1942, journalist Larry Tajiri reported that a Japanese man on West 66th street had been assaulted by a Filipino. In March 1942, a dozen men rooming on West 65th street were arrested by the FBI on suspicion of failing to register as enemy aliens.

In January 1944 the Daily News reported that James Shinto (ie. Ditrochi Sakamoto) a Japanese immigrant living at 146 W. 65th Street, had sued police Property Custodian Morris Simmons over $684 recovered during a prewar gambling raid on a restaurant where he worked as a cook. Shinto insisted that the money was his life savings, entrusted to the restaurant’s owner, but stated that he was wary of bringing a lawsuit because of fears of racial discrimination. Municipal Court Justice Harold Crawford asked the 6 jurors to take a special oath that they would not be swayed by the plaintiff’s race.

The mass removal and confinement of West Coast Japanese Americans (often called the Japanese American internment) led to a new growth of population. As individuals whom officials deemed “loyal” were allowed to leave the ten government camps, many elected to migrate to New York, which had remained the largest “free” Japanese American community during the war, to take up jobs or attend school. A network of social welfare agencies, anchored by the activist group Japanese American Committee for Democracy, stepped up to aid the newcomers.

As working-class Issei migrants, in particular, left camp and arrived in New York, they settled into San Juan Hill. Many moved into the 65th Street rooming houses, alongside existing residents. By 1952, Uzaemon Tahara, longtime manager of the Ichiriki, had purchased both it and the Taiyo. The New York Japanese American Directory 1948-1949 listed addresses of at least 76 people living in the neighborhood in those years.

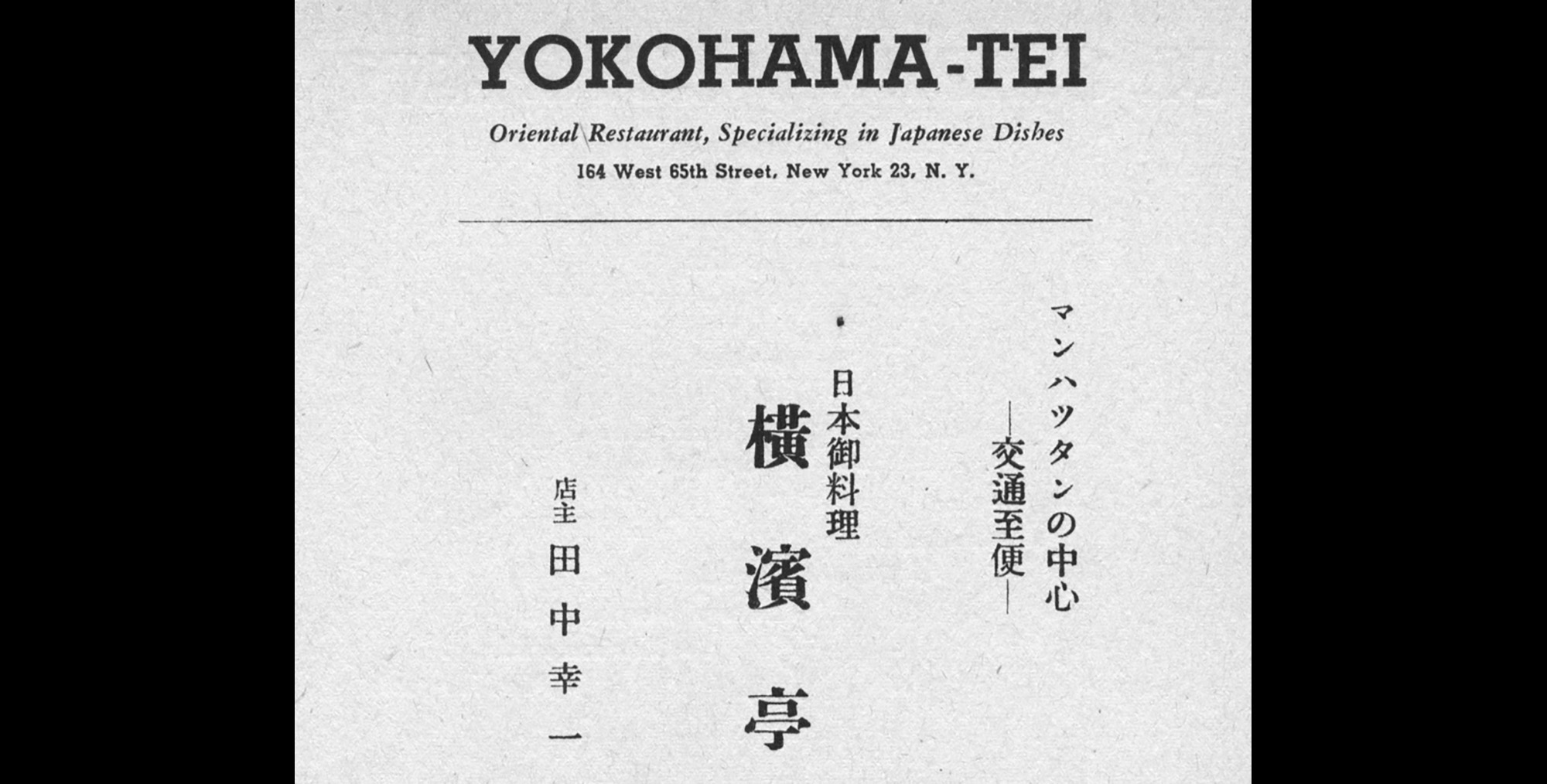

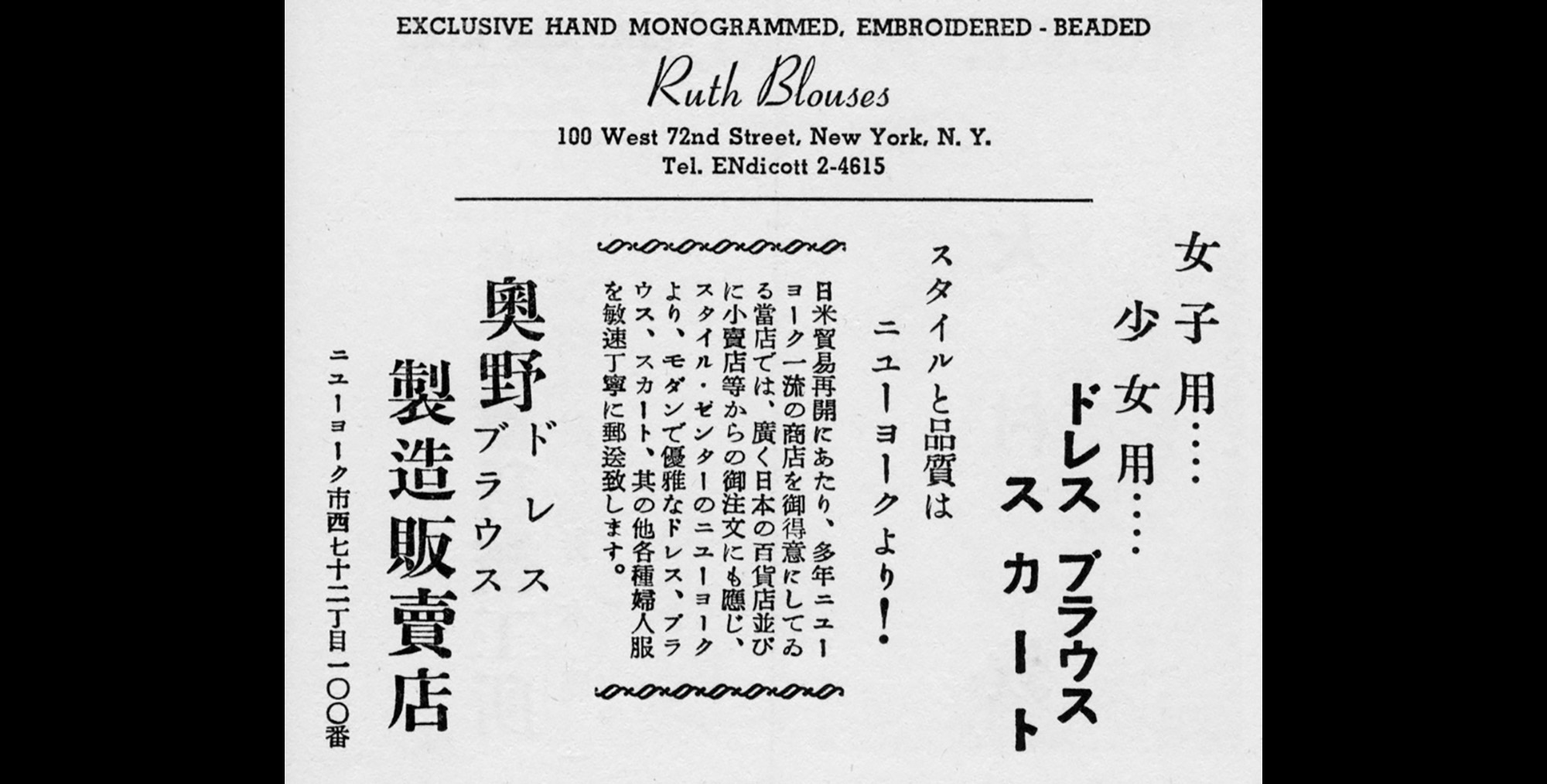

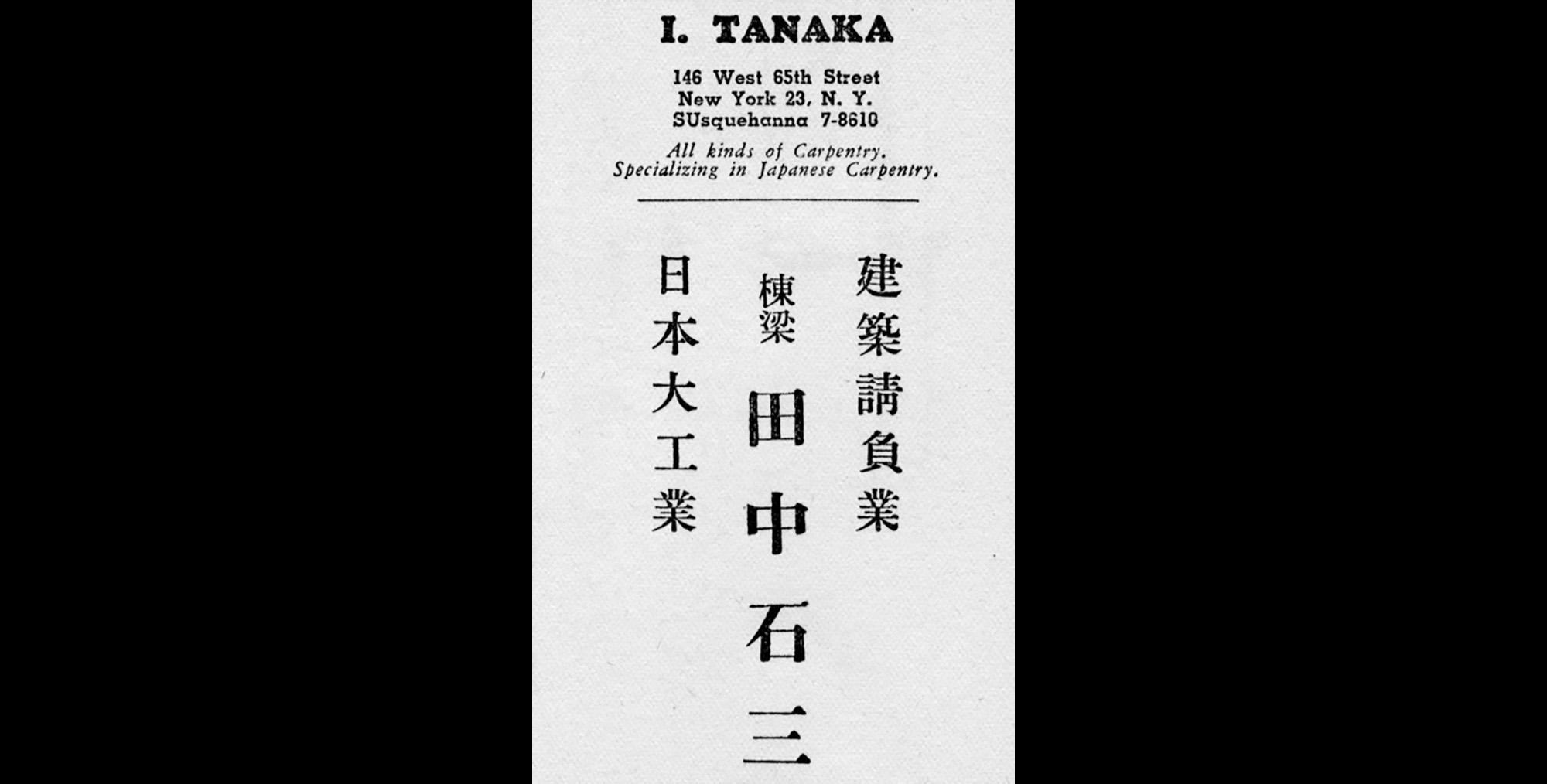

Various Japanese-owned businesses opened on West 65th Street during the postwar years: Ishizo Tanaka, a carpenter, had a shop at No.146. The E.L. Sauce Company at No. 144 morphed into a branch of Sunrise Rice Cake. The Yokohama-Tei Restaurant was located at No. 164. Nearby were Okuno Cultured Pearls, at 100 West 72nd Street and the Westside Pet Shop at No. 161. The offices of Drs. Iwamoto and Tsuchiya remained on West 71st Street. In addition, Dr. Peter Yoshitomi, the city’s first Nisei dentist, opened an office in the Alamac Hotel at Broadway. George Sugai operated a dental laboratory at 138 West 67th Street.

San Juan Hill’s residents became embroiled in drama in 1947, when two year-old Robert Lorentz disappeared. Police found him in the home of Helen Shiro, the wife of a Japanese restaurant worker, on West 64th Street. Newspapers reported that Shiro had picked Lorentz up on the street and taken him to her home, where she kept him overnight and washed his clothes. Threatened with charges of reckless endangerment, she pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct, along with a psychiatric evaluation.

Unlike their Issei counterparts, Nisei resettlers tended to avoid San Juan Hill, a working-class neighborhood with few amenities and a reputation for crime. Instead, they congregated in the so-called “umeboshi” district near Columbia University, or in Inwood at the north tip of Manhattan. However, some Nisei did settle in the area. The 1950 census listed Albert Kanzaki, who worked at an import/export firm, as living with his wife and children on West 69th Street. David Matsushita, a horologist for watch repair firm, lived at 148 West 65th Street with his wife and children. Mary (Yuri) Kochiyama, who would gain fame as an activist after moving to Harlem, lived with her husband and children at 249 West 62nd Street.

An interesting footnote to the Japanese presence in San Juan Hill: Even before Lincoln Center came into being, the neighborhood boasted some outstanding performing artists. In 1935, when Hawaiian-born tenor Royden Susu-Mago, a former Julliard student, came to New York to audition for the National Broadcasting Company, he took up residence in an artists’ collective at 246 West End Avenue. Aiko Tashiro, a pianist and social activist who had taught at Bennington College during World War II, settled in New York in 1945 and served as an accompanist for dance classes and singers—notably African American soprano Marion Downs, with whom she travelled on recital tours. Aiko Tashiro took an apartment at 50 West 69th Street. There she met a fellow tenant, Shigeki Hiratsuka, a mechanical engineer and World War II veteran. A romance blossomed and the two were married in 1947. Ruby Yoshino, a rising operatic soprano on the prewar West Coast, toured the East during 1944 with a series of concert-lectures to raise public awareness of the plight of Japanese Americans. After the war she moved to New York and lived with her husband, pianist and vocal coach Rudolph Schaar, at 50 West 67th Street. In 1948 Yoshino joined African American tenor Napoleon Reed and others in forming the One World Ensemble, an interracial “quartette” dedicated to showing that music could transcend “racial and nationality barriers.”

The presence of Japanese Americans and other Asians in San Juan Hill tended to pass unnoticed, both at the time and since. Yet their vital contribution to the district’s social, economic, cultural and religious landscape—and its culinary diversity—well deserves commemoration.

Notes

1 Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2012, pp. 53-55. On New York’s early Japanese communities, see T. Scott Miyakawa, “Early New York Issei Founders of Japanese American Trade,” in Hilary Conroy and T. Scott Miyakawa, East Across the Pacific: Historical and Sociological Studies of Japanese Immigration and Assimilation, New York, ABC-CLIO, 1972, pp. 156-186; Mitziko Sawada, Tokyo Life, New York Dreams: Urban Japanese Visions of America, 1890-1924, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1996; Eiichiro Azuma, “Issei in New York, 1876-1941,” Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Summer 1998, pp. 5-8; Daniel H. Inouye, Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 1876-1930s, Denver, University Press of Colorado, 2019.

2 On the boardinghouses and Japanese American life in the West 60s, see Inouye, Distant Islands; Charlotte Brooks, “Forgotten Community of the West 60s,” Asian American History in NYC, blog, https://blogs.baruch.cuny.edu/asianamericanhistorynyc/?p=326

References

“Boguchi! Boguchi! Shoes for Baby,” The Evening World, February 4, 1920.

Helen Worden, “New York,” The Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, September 1, 1934.

“Japanese Kills Self, Wounds White Wife,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 29, 1935.

“NYK Team Wins Basketball Title,” The Japanese American Review, February 24, 1940.

“Job Conference wIll be Held in New York City for Nisei,” The Japan-California Daily News, August 31, 1941.

Larry Tajiri, “New York Dateline..by Tajiri,” Rafu Shimpo, January 8, 194.

“Arrest of Butler Leads to Roundup of 18 J-ps in City,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 3, 1942.

“Jurors Sworn to Fairness on J-p’s $684 Suit,” New York Daily News, January 29, 1944.

“Missing Boy Found Safe,” New York Times, May 29, 1947.

“Baby Keeper Sent to Bellevue,” New York Herald Tribune, September 14, 1947.

Further reading

New York Japanese American Directory, 1948-1949. New York: Japanese American News Corporation, 1948.

Diane C Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Minnesapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Peter Saiwen, Upper West Side: A History and Guide. New York, London: Abbeville Press, 1989.

Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki (Michael Hotz,ed.), Holding the Lotus to the Rock: The Autobiography of Sokei-an, America's First Zen Master. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003.

Greg Robinson and Jonathan Van Harmelen, “Nisei Singer and Civil Rights activist Ruby Hideko Yoshino,” in The Unknown Great: Stories of Japanese Americans at the Margins of History. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2024, pp. 160-164.

Greg Robinson, “The Amazing Tashiro Family - Part 3: Aiko Tashiro—Writer, Musician, and Activist,” Discover Nikkei, December 11, 2023, https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2023/12/11/aiko-tashiro/