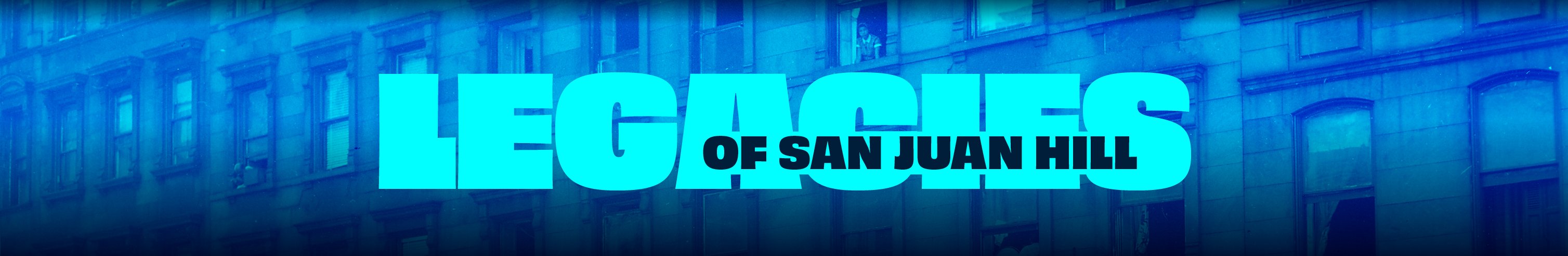

Ariana DeBose, Ana Isabelle, and Ilda Mason in West Side Story (2021).

Photo: Niko Tavernise/© 2020 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation.

When History Plays a Starring Role:

Puerto Rican Writers, West Side Story, and San Juan Hill

March 26, 2024

by Virginia Sánchez Korrol, Professor Emerita, Brooklyn College

In the spring of 2019, Steven Spielberg invited me to speak about New York Puerto Rican history to the cast, crew, and creative production team of a new film version of West Side Story. My immediate inclination was to scan my bookshelves in search of the written record. Our Puerto Rican mid-century writers were rarely referenced in textbooks, or educational settings and I wanted this influential gathering of filmmakers to become familiar with my mid-century Nuyorican city through the lens of our chroniclers from our first encounter.

Because he wrote in English, Jesús Colón’s work topped my list. In his opinion, the 1957 Broadway production of West Side Story had disserviced Puerto Ricans by failing to convey their true history, culture and traditions. To understand Colón’s perspectives about Puerto Rican life in New York during this period, his articles and sketches are indispensable. So are Bernardo Vega’s memoirs, and the contributions of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. I trusted the vast experience and activist legacy bequeathed to us by these three legendary Boricua narrators could easily cover a century of Puerto Rican life in the city.

In the plain language of the people, Jesús Colón penned vignettes based on his experiences unveiling the difficult conditions confronting the early migrants in the inhospitable New York environment. His commitment to community sprang from the time he was a lad in Puerto Rico eavesdropping at the window of the local cigar factory as the lector read to the workers while they rolled cigars. Inspirational to the young Afro-Boricua, the reader similarly enlightened the tobacco workers who had selected him or her from among their ranks. Lively discussions followed the twice daily readings of newspapers, existentialist novels, and socialist tracts, molding tobacco workers into the best informed among the proletariat.

Like Colón, Schomburg was a mere teenager when he arrived from Puerto Rico in 1891, but age didn’t stop him from joining the New York-based struggle to shatter the shackles that bound Cuba and Puerto Rico to Spain. By 1892, he headed Las Dos Antillas, one of hundreds of international clubs supporting Cuban and Puerto Rican independence. Despite their struggles for freedom, the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor that ignited the Spanish-American War in 1898 led to establishing a U.S. protectorate over Cuba and a colony in Puerto Rico.

The inordinate outpouring of grief and anger throughout the city was palpable, and Remember The Maine; to Hell With Spain, became its battle cry. The construction of the Maine Monument at the West 59th Street Merchant’s Gate to Central Park honored the 266 casualties of the disaster, among them African Americans who worked as oilers on the ship. Fittingly, the adjacent San Juan Hill was one of the largest African American and Black Caribbean neighborhoods in the city and may have been named for a decisive battle in the war. By 1915, Schomburg was residing there immersed in archival preservation with journalist John Edward Bruce for The Negro Society for Historical Research.

Schomburg’s extensive collection of books, articles, pamphlets and ephemera was installed at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library in 1925. Yet, despite its importance, neither Schomburg himself, nor his collection, received mention in a February 1956 New York Public Library brochure citing resources on New York’s Puerto Ricans and Puerto Rico, a testimony to the irrelevance of the group at that time.

It was Bernardo Vega, the cigar maker turned journalist and labor organizer who recognized the urgency of documenting and empowering Puerto Rican roots in New York City. He valued his people’s historical record of achievements and contributions. An undisputed resource for the education of generations of Nuyoricans growing up in diaspora, Vega penned a game changer, an eyewitness chronicle based on a century of Puerto Rican life contrary to the then prevailing deficit images of the group. He wrote of Puerto Rican working-class enclaves, their mutual aid societies, hometown clubs, stores, religious and socio-cultural activities, and a grassroots organizational network whose foundational seedlings first sprouted in the mid–19th century.

Most significant for the film’s young cast, the postwar period pictured in West Side Story was fueled by the archipelago’s industrialization agenda. Displaced Puerto Rican workers left for New York in multitudes. They came for jobs; or because they were recruited as a cheap labor pool; or they had extended family in the city; or to study; or simply because they had few other alternatives for a viable future in Puerto Rico. But in a city facing labor unrest, housing shortages and inadequate resources, they became a “problem.” Deriding the unwelcomed migrants as urban misfits—a cohort of uneducated and unassimilable foreigners who incubated tropical diseases —the mainstream press intensified its slanders against the population. Low-income communities like San Juan Hill or the South Bronx were declared Puerto Rican slums by Robert Moses, eligible for demolition.

Initially, my talks centered on the immediate effects of urban renewal, but soon our conversations broached a broader sweep of historical events. The actors were curious about the colonial status of the Puerto Rican archipelago, women’s roles, and race relations. Producer Kevin McCollum recommended my books, and knowing the cast was familiar with From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York City, I began to draw upon my lived experience. I had come of age in the mid-century when Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods were fodder for demolition under the guise of urban renewal, and drugs and street gangs destabilized our working-class communities. Among my peers, girls aspired to futures within the cult of domesticity, so I had much in common with the characters in the script.

Within a month of my last lecture, executive producer Tony Kushner, invited me to become the historical consultant on the film. Drawn to the project by his brilliant script, Steven Spielberg’s visionary ideas of “making a film for our times,” and the sincerity of communal commitment to authenticity I felt from the cast and the creative production team, I accepted the offer. I had lived through the pros and cons of the iconic 1961 version for decades, but stilled the antiquated nudges buzzing in my ear about its stereotypical images. These were different times, and I believed that I, and other Latinx consultants, could make a difference.

After all, we Boricua kids had grown up on Saturday matinees immersed in the film genres of cowboys, and brown-faced Indians with demeaning accents; Eurocentrism, and the Hollywood musical extravaganza. To see our people finally take center stage for the very first time in an American movie was cause for celebration. Moreover, we understood West Side Story was not a documentary; it was, and still remains, a creative work of art set in a specific place and time. If the new version of West Side Story offered us a chance to chime in on a more authentic representation of the Puerto Rican storyline I certainly wanted to be there.

Spielberg’s reputation for pushing boundaries was legendary. By the time I came onboard, he had already boned up on the dissident controversies of West Side Story. Envisioning the artistic advances an updated cinematographic production could make, he found resonance in the universality of the theme: its outstanding musical score, star-crossed lovers, and the immigrant search for opportunity and a viable existence in America. Spielberg spoke of creating a more nuanced version of the story, not on remaking an iconic, award-winning classic. Then he reached out to academics, informed individuals, dialect coaches, and the Latinx community to help make it happen. Every member of the Puerto Rican Sharks was to be of Puerto Rican or Latinx descent, and dozens of us who worked behind the camera were also Latinx.

Screenwriter Tony Kushner had prepared extensively before scripting the story, reading every book he could find about the postwar Puerto Rican migration, the hard-scrabble neighborhoods that sheltered them, and the settings from which they came. He crafted a realistic narrative as he immersed himself in researching the archives, especially the holdings of the City University of New York (CUNY)’s Center for Puerto Rican Studies. Throughout the year it took to cast the film, Cindy Tolan and her advisers also relied on research. Along with members of the creative core, she auditioned hundreds of talented actors in New York, Florida, California, Puerto Rico, and Latin America. And the native-born Puerto Rican, Rita Moreno, who received an Oscar for her role as Anita in the 1961 version, had actually lived the migrant experience. Now, sixty years later, she was an executive producer on this film, and would portray Doc’s widow, the embodiment of an elderly Puerto Rican woman who had endured the neighborhood’s ethnic change.

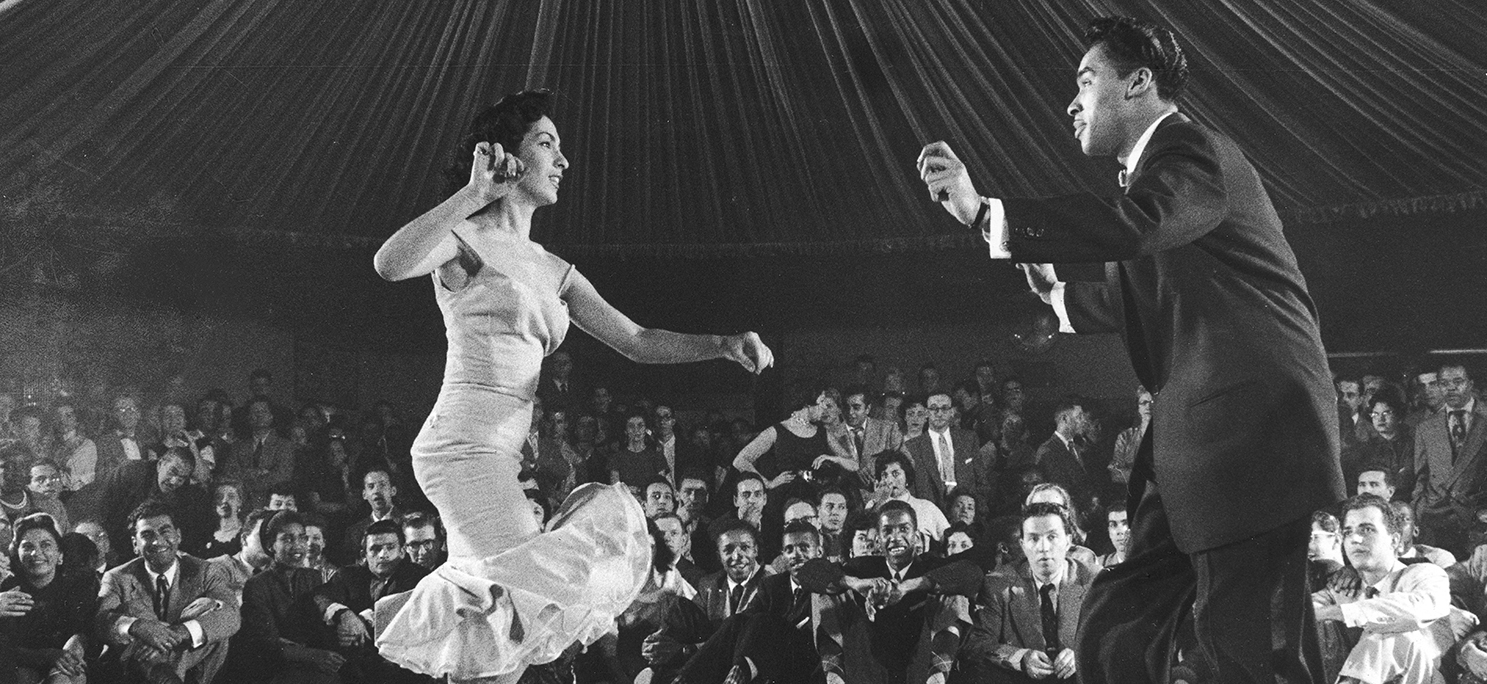

A lot had happened in those sixty years, and I was beginning to appreciate that the point of departure between the 1961 film and the 2021 version was fifty years of scholarship produced or recovered through the academic field of Puerto Rican Studies. The 1961 Academy Award- winning film inspired by Chicano street riots in Los Angeles, and produced by the brilliant team of Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents, Stephen Sondheim and Jerome Robbins ripped its storyline from the headlines at a time of virulent discrimination against the Puerto Rican community. While the creators understood discrimination, they professed to know next to nothing about Puerto Ricans. A dearth of academic research on Nuyoricans served the creative team in the 1950s compared to the explosion of knowledge on the subject by the 21st century.

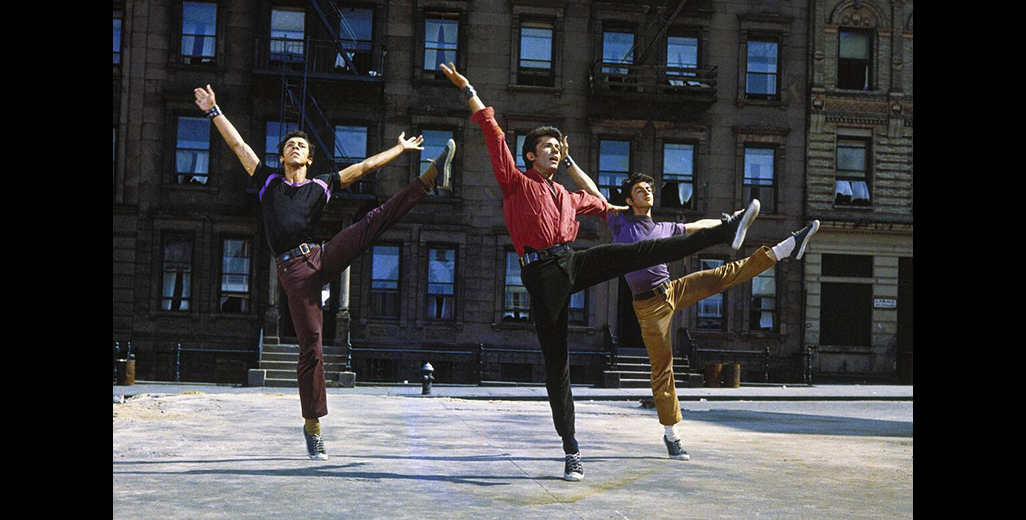

Spielberg’s film version embarked on charting a course that broadened the story to include the impact of urban renewal on powerless communities. From the iconic words of Nationalist leader, Albizu Campos, and the Puerto Rican flag that opens the story, to the Spanish dialogue sans subtitles; and from cultural symbols, families, bodegas and entrepreneurship, to Puerto Rican women exercising agency, supporting households as factory workers, or seamstresses, history was playing a starring role. The film pays homage to San Juan Hill’s culturally vibrant, tenement community of low-income, working-class African Americans and Puerto Ricans who inhabited the neighborhood in the 1950s. And nowhere is the innate importance of language more significant than in the Sharks’ rendition of La Borinqueña, the revolutionary Puerto Rican anthem and the only Spanish song in this musical.

The young cast that comprised the Jets and the Sharks were some three generations removed from that of their grandparents, many of whom arrived as part of the great postwar migration. It meant terminology, or Spanglish, which served as markers for their grandparents and my generation were no longer in use. Accents, pronunciation, and slang words changed accordingly over time. The Spanish of recent arrivals differed from those who were born, or had spent years, in the city. Indeed, by the fourth or fifth generation, many Puerto Ricans in the U.S. only spoke English.

As the leads, Rachel Zegler, Ariana DeBose, David Alvarez, and Josh Andres Rivera began to delve into the lives of their characters, Tony Kushner developed backstories for them. With ten members of the cast, he organized the “Puerto Rican Talmudic Study Group,” a study/discussion group that met regularly to dissect the elements of language, culture and character. In similar fashion, vocal coach, Jeanine Tesori, teased out the particularities of language, character and meaning in the music and lyrics for authenticity. Such interactions permeated the set, creating a relationship between the cast, the professionals, and advisers that I found encouraging.

When the pandemic delayed the film’s release for a year, we remained actively involved. Producer Kristie Macosko-Krieger continued to call on our services, and we became more of a theatrical company than a film crew according to Spielberg. When I proposed a lecture series based on both versions of West Side Story for undergraduate students in the Department of Puerto Rican and Latino Studies at Brooklyn College where I was Professor Emerita, Kristie supported the idea. Department chairperson, Dr. María Pérez y González and I envisioned an online series of eight zoom conversations that would be embedded into an existing undergraduate course, “New York Latinx Culture and the Arts,” but made available throughout the entire CUNY system. Here was a totally unique educational experience for our students, most of whom were first generation collegians. Our students were exposed to some of the most distinguished experts in the film industry, and they, in turn, would learn from our community.

As hosts of the series, Professor Pérez y González and I introduced issues such as the lack of Latinx representation in the movie industry; the role of women in West Side Story; or how our students could carve careers in media. The experts, Juan González, Ernesto Acevedo-Muñoz, Victor Cruz, Bobby Sanabria, Tony Kushner, Jeanine Tesori, and Steven Spielberg all gave generously of their time and expertise. The film’s premiere in December 2021, became the capstone for the stellar semester, and the lecture series captured the making of West Side Story, (2021) for future students and teachers.

When history plays a starring role, it is bound to be a layered one. As the 2021 film went on to receive well-deserved accolades in the industry, an unanticipated contribution has been the illumination of the lost neighborhoods of Lincoln Square and San Juan Hill. The recovery and commitment to preserve the stories of a community of politically powerless residents whose contributions and creativity had been forgotten has taken on new meaning as institutions like Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and the Center for Puerto Rican Studies create initiatives that address the legacy of San Juan Hill.

Resources

1. Jesuús Colón. A Puerto Rican in New York and Other Sketches. International Publishers. N.Y. Second Printing, 1982.

2. Jesús Colón. The Way It Was and Other Writings. Edna Acosta- Belen and Virginia Sánchez Korrol, (eds). Arte Público Press, Houston. 1993.

3. Cesar Andreu Iglesias. Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto Rican Community in New York. Monthly Review Press, N.Y. 1984.

4. Sánchez Korrol, Virginia. From Colonia to Community: The History of Puerto Ricans in New York. California University Press. 1994.

5. West Side Story Lecture Series The Brooklyn Connection. https://www.Brooklyn.cuny.edu

6. Laurent Bouzereau. The Making of the Steven Spielberg Film West Side Story. Abrams, N.Y. 2021.