Japan Products Company, Ichiriki boarding house, and Taiyo boarding house, circa 1940

Photo: Courtesy of Municipal Archives, City of New York

Block of Survival: A Japanese American Enclave in San Juan Hill

March 13, 2025

by Daniel H. Inouye

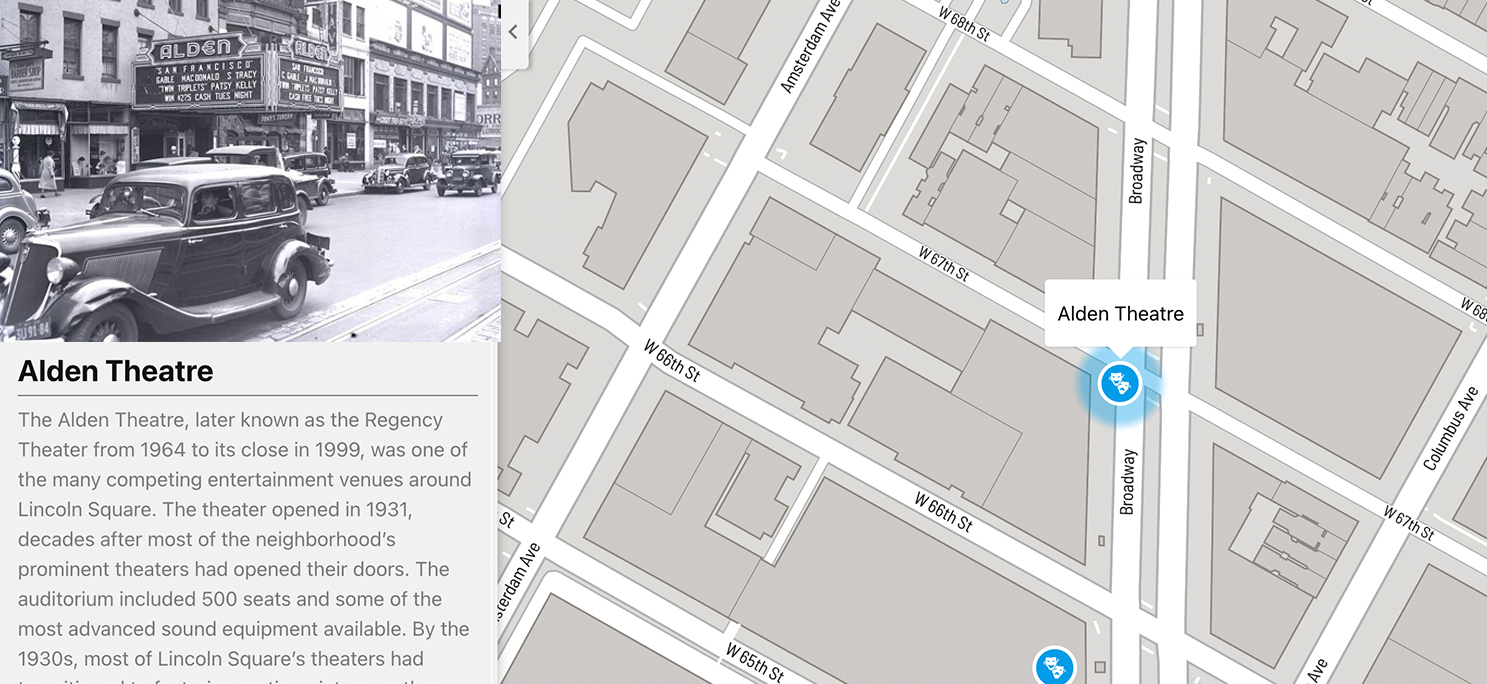

Between the 1910s and 1950s, there was a tiny enclave of Japanese Americans who resided on one block of West 65th Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, in the San Juan Hill neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The New York City Board of Aldermen officially named the area Lincoln Square in 1906, the same year that the Shubert Organization opened the Lincoln Square Theatre on Broadway between 65th and 66th Streets. The Japanese Americans on West 65th were part of a comparatively larger community of ethnic Japanese residents of New York City that ranged between 2,000 and 5,000 persons during these decades.1 This was a challenging time for the community. While they did not experience the virulence of the anti-Japanese movement in California and elsewhere on the Pacific coast, they had their own obstacles to overcome.

The ethnic Japanese residents of New York included issei (Japanese immigrants; literally “first generation”), nisei (American-citizen children of issei; literally “second generation”), Japanese overseas or exchange students, Japanese businessmen, and Japanese consular officials. The New York Japanese community lacked a central business or residential district as a consequence of its small population, as well as divisions along class, religious, and especially status lines. While similar divisions existed in most Japanese immigrant communities in North America, the divisions in the New York community were more pronounced due to its higher percentage of Japanese businessmen.2

The enclave on West 65th Street, which consisted of between 60 and over 100 ethnic Japanese, the vast majority of whom were issei, was one of numerous small communities of Japanese and Japanese Americans that have existed in and around New York City over the past 140 years. During the decades preceding World War II, there were Japanese conglomerates, offices for steamship lines, and banks in the Financial District on Lower Broadway. Japanese porcelain tableware trading companies were located in Chelsea, while Japanese silk trading companies were situated in Murray Hill.

The residences of ethnic Japanese were spatially scattered across Manhattan and other parts of the tristate region. Before the war, Japanese businessmen, who rotated in and out of New York on a periodic basis, and their families lived in rental apartments on Park Avenue in Murray Hill and Midtown, while some managers and executives resided on tony West End Avenue on the Upper West Side.3

The cost-of-living was typically a major factor in determining where people resided. Racially restrictive covenants in leases and deeds also limited where persons of Japanese ancestry could reside in New York City. When such covenants were not present in contracts, some building owners still declined to lease apartments or sell houses to “Orientals.” The first identifiable, issei community in New York dates back to the 1890s. This community consisted of several hundred skilled and unskilled male laborers. They lived either on US Navy ships docked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, or in rooming houses or apartments, concentrated on Sands Street, adjacent to the Navy Yard. The majority of these men worked as messmen for the US Navy, while others worked onshore as domestic and restaurant workers.

By the 1910s, the issei community around the Brooklyn Navy Yard had disappeared. Issei messmen had lost their jobs due to the enforcement of naval orders that prohibited the employment of non-US citizens in the navy. The vast majority of Japanese immigrants, as well as most other Asian immigrants, were ineligible for US citizenship pursuant to then-existing American naturalization laws, and subsequent judicial decisions. Japanese aliens were commonly referred to as “aliens ineligible to citizenship.” Seeking gainful employment, residents scattered to different parts of the city, other states, and other countries.4

Tiny issei working-class communities emerged in Fort George and Inwood in Upper Manhattan, and on Coney Island in Brooklyn. A small bachelor laborer community also formed in San Juan Hill, another working-class neighborhood. This neighborhood had large African American and West Indian populations since the 1890s, and also included German, Irish, Italian, and other European ethnic groups. A sizable Puerto Rican community formed there after World War II.

Issei laborers chose San Juan Hill—which was crime-ridden and also had a history of race-related violence, and later became associated with illegal heroin trafficking—because housing rents were low. They settled primarily in two, issei-owned rooming houses on the 100 block of West 65th Street—Ichiriki at 146 and Taiyo at 148. The rooming houses each had several owners-managers over the years. The best remembered were Ryuichi Murakami at Taiyo and Uzaemon Tahara at Ichiriki. During the early 1930s, Murakami converted the street level floor of Taiyo into a makeshift Japanese restaurant. Their neighbors included influential modern jazz composer and pianist Thelonious Monk, who resided for much of his life in the Phipps Houses on West 63rd Street. Other jazz musicians also lived in the neighborhood. Benny Carter, the alto saxophonist, trumpeter, composer, arranger, and conductor, lived with his family in a tenement on West 63rd Street when he was a youth during the 1910s and early 1920s.5

The issei bachelors included those who had immigrated to America as students seeking education as a means to either skilled, professional, or entrepreneurial employment. Most of them lacked adequate savings or financing for their education. Some worked for well-to-do American families as domestic laborers to pay for tuition, books, and living expenses. Their employers referred to these student-laborers (dekasegi-shosei) as “schoolboys” and “boys.” Due to the difficulties of holding full-time jobs, while attending school on a full-time basis, however, it was common for issei students to withdraw from college and not return. Others who completed their college degrees experienced pervasive, race-based employment discrimination in most professional sectors, and were consequently unable to obtain employment connected to their degrees.

The preponderance of these men became permanent laborers. In New York City, they worked as domestics, chauffeurs, waiters, cooks, dishwashers, concession stand operators at amusement parks, and day laborers. It was common for laborers to reside in New York for a short time period, and then leave the city in search of better jobs. Due to the lack of income sufficient to support a wife and children, a sizable number of laborers became life-long bachelors.

Some student-laborers became members of the Young Men’s Association (Seinenkai), a social organization based in Manhattan. Over the ensuing decades, the name of the organization remained the same, as their members aged from young to middle-aged to old men. Their dreams of prosperity, as well as the organization itself, faded away. Japanese students who entered the United States after the Japanese exclusion clause to the Johnson-Reed Act went into effect in 1924 were generally more affluent, and shunned the organization, associating it with laborers and failure.6

Along with laborers and rooming house operators, the West 65th Street community included others who operated small retail businesses. With a few exceptions, issei merchants established small businesses in working-class neighborhoods because they could not obtain commercial loans from banks. With rare exceptions, American banks in New York City discriminated on the basis of race. These banks routinely declined to issue commercial loans to racial minorities to enable them to start or expand their businesses. Many issei merchants also could not turn to Japanese banks in the city because such banks only issued commercial loans that related to trade with Japan. In Japanese American communities on the Pacific coast and in Hawai’i, there were ethnic-based credit associations (tanomoshi-ko) that provided loans to ethnic Japanese businesses, however, the sole New York-based tanomoshi-ko had limited funds.7

During the 1920s and into the early 1930s, Tokyo Company, a store that sold Japanese dry goods and novelties, was located at 140 West 65th Street. In 1926, a former ophthalmologist named Dr. Kuro Murase established another small Japanese retail store on West 65th Street. An issei who was born in Hagi in Yamaguchi prefecture in 1880, Dr. Murase had immigrated to the United States in 1911.

Prior to his entry in the grocery business, Dr. Murase had a profitable ophthalmology practice in the Rose Hill neighborhood of Manhattan. He also owned a small-scale import and export business, named Japan Provision Company, at the same address. His business exported surgical instruments to Japan.

His career change occurred after New York health officials forced him to close his practice. He did not possess a medical license to practice ophthalmology in New York, and health officials declined to recognize his Japanese medical license. The closure of his practice came several years after the tragic death of his wife Nobuko Oguri Murase and daughter Kiyoko in the 1918–20 Spanish flu pandemic, and not long after his remarriage to his second wife Miyo Ikeda Murase. He and Miyo had two children.

After the closure of his ophthalmology practice, Dr. Murase retooled his export business into a retail merchandise store at 150 West 65th Street. The store sold Japanese groceries and produce, along with assorted Japanese sundries and novelties. He later moved the store to 144 West 65th Street, and changed its name to Japan Products Company. Before World War II, Japan Products Company was one of three stores in New York City that sold Japanese groceries. He also owned and operated Daruma Japanese Restaurant in Midtown Manhattan.8

Following the Japanese military attack on US naval battleships at Pearl Harbor, Hawai’i in December 1941 and the entry of the United States into World War II, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents interrogated and arrested Dr. Murase, and confiscated his businesses. He was not charged with any crime. The US government nevertheless incarcerated him at the Ellis Island Internment Camp, and subsequently transferred him to the Santa Fe Internment Camp in New Mexico for the duration of the war. He died in 1947.9 Dr. Murase became part of the federal government’s selective roundup and imprisonment of about 3,000 so-called “enemy aliens” of German, Japanese, and Italian ancestry from across the United States. Although Dr. Murase was a legal US resident, he was not an American citizen, and, as a person of Japanese ethnicity, ineligible to US citizenship. Enemy alien internment was separate from the subsequent mass removal and incarceration of both Japanese aliens and American citizens of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific coast states. The administration of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt was responsible for both policies.10

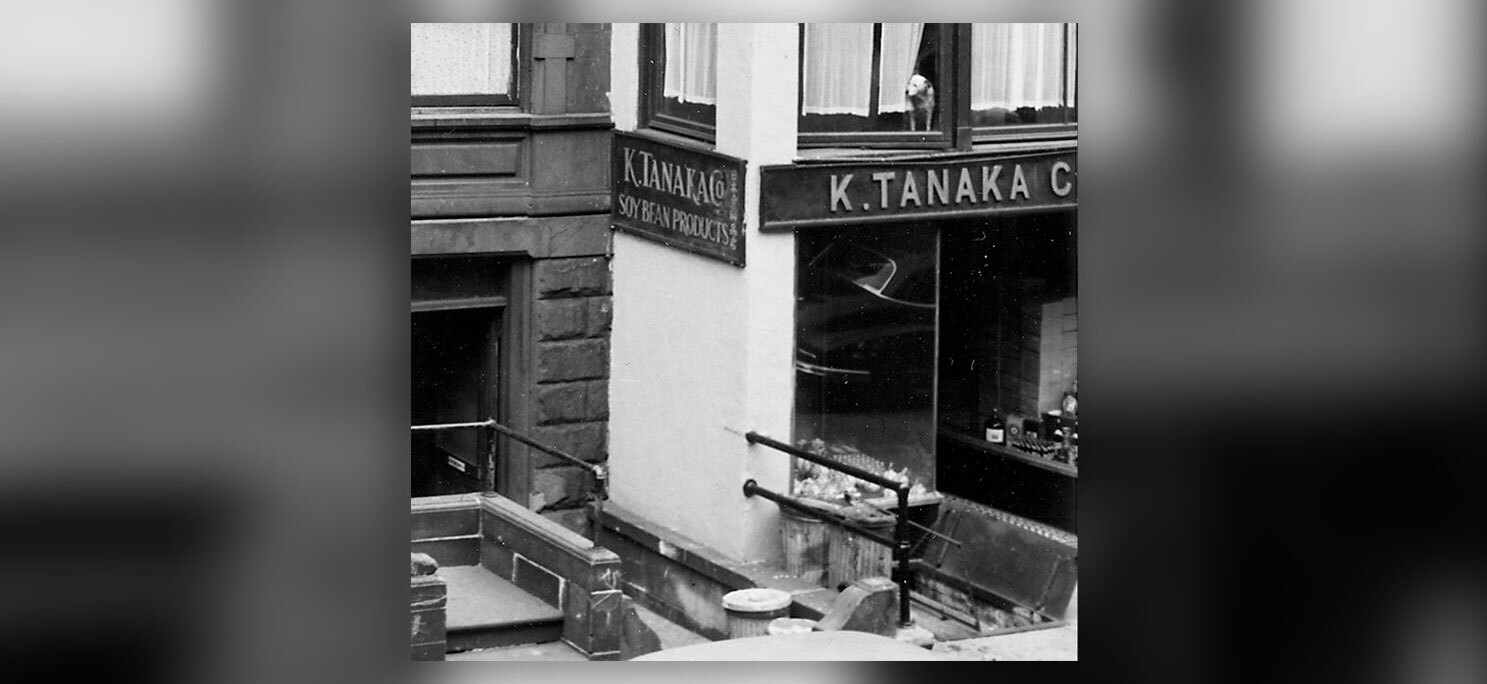

In 1943, Kaijiro Tanaka purchased the building, fixtures, and remaining merchandise of Japan Products Company at 144 West 65th Street from the Office of Alien Property Custodian, the office within the US Department of Justice that had seized control of Dr. Murase’s businesses. An issei who was born in Fukuoka prefecture in 1885, Tanaka had immigrated to the United States in 1906. He initially worked as a chauffeur in Denver and New York City, and then established a small Japanese confectionery/bakery in Manhattan. His store became known especially for senbei—a baked rice cracker snack, of different shapes and sizes, that is produced in both savory and sweet varieties.

Soon after the Pearl Harbor attack, FBI agents questioned Tanaka and searched his home and business. The FBI required Tanaka to close his business but did not arrest him. During the war, he reestablished his senbei business on East 53rd Street in Midtown Manhattan near a Japanese Christian church.

Tanaka’s purchase of Dr. Murase’s former store enabled him to expand his freshly-made products beyond baked goods. Along with selling Japanese groceries, vegetables, and porcelain ware, Tanaka produced and sold Japanese tofu at his store on West 65th Street. Unlike Chinese tofu which uses calcium sulfate as the coagulant, Japanese tofu uses nigari (concentrated mineral-rich seawater with much of the salt content removed) as the coagulant. He would soon become better known in the community for his tofu than for his senbei. Tanaka gave his store an unusual name—E. L. Sauce Oriental Food Products Company, which was also known as E. L. Sauce Company. Due to the ongoing war, Tanaka likely chose a name that would obscure any Japanese connotation. By 1948, when Japanese food, art, porcelain tableware, and fashion were becoming in vogue in the United States, he had renamed the store K. Tanaka Company, Inc. A widower, Tanaka married Kikue Kodama, the owner and operator of Suehiro Restaurant, after the war.11

During World War II and the early postwar years, there were nuanced changes to the community on West 65th Street. Some nisei rented rooms in the rooming houses on West 65th Street. This came about due to the war and its aftermath, and the wind-down of the mass removal and incarceration policy. In 1943, the War Relocation Authority (WRA)—which operated the ten camps that held about 124,000 Japanese Americans who had been involuntarily removed from their homes on the Pacific coast and southern Arizona, and incarcerated in the camps—simplified its indefinite leave clearance policy to enable prisoners (euphemistically referred to as “evacuees”) who met specified criteria to depart the camps. The criteria included resettling in a WRA-approved location outside the removal areas, determination of loyalty to the United States, and either having a bona-fide job offer, or having arranged to reside at a WRA-sanctioned hostel, hotel, or private residence.12

An estimated 3,000 prisoners, largely young adult nisei, men and women, between the ages of 18 and 30, resettled in New York City. To meet their immediate housing needs, the Church of the Brethren and the American Baptist Home Mission Society established a hostel for them in Brooklyn Heights. The released prisoners also found housing in other hostels, apartments, and rooming houses. After the war, nisei veterans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Military Intelligence Service (MIS), and other US Army units settled in New York City to attend college on the GI Bill. Nisei from Hawai’i also came to the city to attend college and other institutions of higher education. The new arrivals more than doubled the size of the New York Japanese population, which had dwindled to 1,750 by mid-1942.13

William (“Bill”) Kochiyama, a nisei, native New Yorker, and 442nd combat veteran, his nisei wife Mary (who later went by Yuri, short for her middle name of Yuriko), and their six children lived in San Juan Hill between 1948 and 1960. Both Bill and Yuri had been imprisoned as part of the mass incarceration during the war. Bill’s imprisonment occurred by happenstance. He had traveled with a friend to California in 1940 to experience life out there. He spent about a year in prison, the majority of the time at the War Relocation Center in the desert of Topaz, Utah. In 1944, when the US government permitted Japanese Americans to serve in the US Army, Bill volunteered, leaving Topaz to join the 442nd. If he had remained in New York, Bill, an American citizen born in Washington, DC, would not have been incarcerated. Yuri, who was from San Pedro, California, was incarcerated principally at the War Relocation Center in Jerome, Arkansas. The Jerome camp was built on swampland.

Bill and Yuri married in New York City in 1946. Two years later, they moved into an apartment in the Amsterdam Houses, a new, nine-acre, public housing complex, situated between West 61st and West 64th Streets on the south and north, and between Amsterdam Avenue and West End Avenue on the east and west. They resided on West 63rd Street.

In 1951, the Kochiyamas formed the predecessor to the Nisei-Sino Service Organization (NSSO), a grassroots organization that assisted nisei and Chinese American veterans of World War II and the Korean War. Activities of the NSSO included organized day trips and “open house” gatherings for the veterans on Friday evenings in the Kochiyamas’ apartment. Yuri and Bill also hosted another “open house” on Saturday evenings. The Saturday gatherings were open to all people, and were well attended by college students. Along with socializing and networking, the weekend conclaves featured potlucks, dancing, live music, and invited guest speakers.

Daisy Bates—the civil rights activist who had organized students, known as the Little Rock Nine, to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957—was a guest speaker at one of the open house events. From Bates, Yuri and Bill gained a greater depth of understanding of the African American Civil Rights Movement, and the importance of becoming involved in the movement. Bates also influenced their decision to reside in Harlem.

In 1960, the Kochiyamas moved to the Manhattanville Houses, a public housing project in West Harlem. While living in Harlem, Yuri was active in the Civil Rights Movement, and later in the Black Power movement, Asian American Movement, Japanese American Redress Movement, and other social movements, while Bill was less active due to the need to provide financially for their six children. Malcom X became a close friend of the family.14

During and after the war, the rooming houses on West 65th Street, joined by a new issei-operated rooming house, Matsuura, at 168 West 65th Street, accommodated small numbers of the new arrivals. Former prisoners who resettled in the Taiyo rooming house at 148 West 65th Street included David and Mae (née Hatasaki) Matsushita and their two young sons, David Jr. and Richard. David Sr. and Mae, who were both nisei and American citizens, were newlyweds when they were removed from their home in Hanford, which is in the Central Valley of California, in May 1942. They had married in April.

David Sr. and Mae were initially incarcerated at the Fresno Assembly Center, which had been built on the site of the Fresno County Fairgrounds. The assembly center provided temporary housing (for six months in their case) pending the opening of the ten camps, which were then under construction. The Matsushitas were then sent to the War Relocation Center in Jerome, where they were incarcerated between November 1942 and June 1944. David Jr. was born in the Jerome camp in June 1943. The following June, the WRA closed the Jerome camp and sent the family to the War Relocation Center at Gila River, Arizona. The camp had been built on the Gila River Indian Reservation. Richard was born in the Gila River camp in September 1944. Both sons would carry the stigma of having been born in an American concentration camp.15

On December 18, 1944, the US Supreme Court, by a unanimous 9-0 vote, held, in Ex parte Endo,16 that the US government could not lawfully “detain” loyal American citizens. The day before the Supreme Court issued its decision, the Western Defense Command of the US Army announced that it would implement a new program granting persons of Japanese ancestry, who were determined “loyal” to the United States, their freedom to return to the Pacific coast beginning in January 1945. On December 13, Henry L. Stimson, the US Secretary of War, had advised President Roosevelt that the Western Defense Command should announce the new policy before the release of the Endo decision, which he correctly predicted would be unfavorable to the Roosevelt administration.17

Although they were no longer excluded from the Pacific coast, the Matsushita family chose not to return to California, and instead decided to make New York City their new home. They had no jobs waiting for them in California. Prior to her incarceration, Mae had been employed as a maid in the private residence of W.C. and Dorothy Tarr in Hanford. W.C. owned a men’s clothing store named the Tarr Clothing Company. David Sr. was a kibei (nisei who received all or part of their primary and secondary school education in Japan, and then returned to live permanently in the United States). His family had relocated to Wakayama prefecture when he was a young child. In 1934, at the age of 18, David Sr. returned to Hanford where he found work as a dishwasher, and later a waiter in a restaurant. David Sr. departed Gila River for Brooklyn, New York in June 1945. By October, when Mae and their two infant children left the camp, David had moved to Manhattan. The family reunited there, and soon made their home at Taiyo. David Sr. obtained a job as a horologist for a wholesale watch repair company.18

Around the time the Matsushita family was resettling in Manhattan, a tiny Japanese restaurant opened for lunch, dinner, and takeout at 164 West 65th Street, two doors west from the Matsuura rooming house. The restaurant owner was an issei named Kokichi Tanaka (no relation to Kaijiro Tanaka). He named the restaurant Yoshino-Ya, and subsequently changed the name to Yokohama-Tei.19

Ishizo Tanaka (no relation to either Kaijiro or Kokichi Tanaka) established another new business on West 65th Street during the mid-1940s. A specialist in Japanese carpentry who was originally from Kobe, Japan, Ishizo Tanaka established his carpentry business on the ground floor of the Ichiriki rooming house at 146 West 65th Street. Tanaka lived on an upper floor of the rooming house.20

In November 1957, the New York City Board of Estimate gave final approval to the Lincoln Square development project. The project concerned 68 acres of land (18 blocks) west and north of Columbus Circle, including West 65th Street, and encompassing much of San Juan Hill. Robert Moses, chair of the New York City Committee on Slum Clearance, spearheaded the project. Moses controlled the $1 billion purse strings of the committee.

As with prior development projects, the city acquired the land primarily through the use of eminent domain, a legal process which enabled the government to seize private property for public benefit. The primary focus of the project was the construction of a performing arts complex.21 The complex would include a large concert hall for the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, an opera house for the Metropolitan Opera, a dance and ballet theater for the New York City Ballet (as well as for the New York City Opera until 2011), a theater for stage plays and musicals, a park and bandshell for outdoor concerts, other smaller performing arts venues, and a combined performing arts library and museum.

Two educational institutions were part of the Lincoln Square development project. Fordham University built its new Manhattan satellite campus on the south side of the square. The five-building campus initially housed a law school, a liberal arts college, and three graduate schools, and later expanded to include other undergraduate schools and a residence hall. A new Juilliard School of Music was constructed on the north side of the square. The new Juilliard building included a small theater with a seating capacity of between 960 and 1,026, dependent on whether the orchestra pit was utilized. The theater served as a venue for Juilliard School concerts, primarily opera, and theatrical plays.22

Supporters of the development project highlighted the creation of the performing arts center and university and college campuses, while detractors, such as Stanley M. Isaacs, a New York City council member, criticized the project for not guaranteeing adequate replacement housing for displaced low-income residents, many of whom were Puerto Rican. The new housing included in the project were luxury residential apartment buildings—notably Lincoln Towers, which consists of six buildings, each 28 stories in height. Another project building was a new headquarters for the Greater New York chapter of the American Red Cross (which was closed in 2005, razed, and replaced by a luxury apartment tower). Harris L. Present, counsel for the Lincoln Square Chamber of Commerce, criticized the project for ignoring “human values.”23

Despite the protest rallies, petitions, and picketing of San Juan Hill residents and lawsuits filed by tenants’ rights groups, the project went forward. The New York Court of Appeals upheld the legality of the project on May 1, 1958. On June 10, the day after the US Supreme Court declined to review the case, thousands of tenants and 800 businesses began relocating from San Juan Hill. Demolition work commenced on July 28. The monitored relocation process, involving 1,647 families on the Lincoln Center site and around 7,000 families on the entire Lincoln Square site, was completed in early 1960.24

Lincoln Center hired a realty company to assist with property management of and resident relocation from the property that it now owned, including the block on West 65th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. Pursuant to Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, families were eligible for federally-funded “relocation bonuses” of between $150 and $550 if they voluntarily relocated. Individuals, such as bachelors, and businesses were ineligible for the federal bonuses.25

Possibly due to the large percentage of bachelors among the Japanese American community of San Juan Hill, the Lincoln Center archives contain just six relocation records for persons of Japanese ethnicity who resided at one of the three rooming houses. All of the six records are for married couples. Five of the six couples relocated to low-cost apartments in Upper Manhattan—the working-class communities of East Harlem, Morningside Heights, and Manhattan Valley (before their gentrification several decades later). A seventh family, the Matsushitas, who unfortunately were quite familiar with forced relocation, moved to an apartment on West 107th Street in Manhattan Valley.26

Prior to relocating his business, Kaijiro Tanaka died in May 1958. Kazuo Nakayama, an associate of Tanaka’s, assumed management of the store. Nakayama had previously worked for Dr. Murase at Japan Products Company. By the summer of 1959, K. Tanaka Company had moved to 326 Amsterdam Avenue between 75th and 76th Streets, about a block from the Beacon Theatre, on the Upper West Side.27

Following demolition of the buildings, the lots that the Japanese American rooming houses and businesses had previously occupied served collectively as an entry/exit to an underground parking garage, which also housed a mechanical space. In October 1965, the Vivian Beaumont Theater, a venue for live plays and musicals, opened in the adjacent lot at 150 West 65th Street. During the mid-1960s, a broad pedestrian bridge was constructed over West 65th Street as part of the design of the new Juilliard School, which was dedicated in the autumn of 1969 and is situated across the street from the lots. The bridge extended directly above the lots, connecting Lincoln Center Plaza to Juilliard.28

In 1993, the New York City Council renamed the block of 65th Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue, Leonard Bernstein Place in honor of what would have been the 75th birthday of the late conductor and composer. Bernstein had served as music director of the New York Philharmonic between 1958 and 1969. His compositions included the music for the Broadway musical West Side Story (1957), which was set in San Juan Hill.29 By coincidence, the city council selected the one block in San Juan Hill that had a Japanese American community to name for Bernstein, while West Side Story, both in its lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by Arthur Laurents, contains no mention of or reference to Japanese Americans.

The garage entry/exit beneath Lincoln Center and the bridge were demolished in 2008 to make way for a new three-theater complex. In 2011, the Film Society of Lincoln Center—which had opened the Walter Reade Theater in 1991 at 165 West 65th Street—completed construction of the new complex, named the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (EBM), on lots that correspond approximately with 144, 146, and 148, the former sites of the K. Tanaka Company store, the Ichiriki rooming house, and the Taiyo rooming house, respectively. The complex features two cinemas that screen art house films, an indoor cafe, and a multi-use amphitheater. That same year, Lincoln Ristorante, a fine dining restaurant that serves Italian fare, opened next door on lots that approximate 138, 140, and 142. A flight of grass-covered stairs leading to a sloped grass lawn replaced a portion of the pedestrian bridge. Planted on the roofs of the film center and restaurant, the lawn creates a small green space in Hearst Plaza on the Lincoln Center campus. The green space lies adjacent to Henry Moore’s two-piece bronze statue, Reclining Figure, which is situated in a reflecting pool.30

Few people know today that this gentrified area, home to one of the preeminent performing arts centers in the world, had once been home to Japanese immigrant laborers. The removal of issei laborers from their rooming houses in San Juan Hill followed decades of struggle and disappointment. Some referred to their plight as shikata ga nai, a Japanese expression which translates in English as “it cannot be helped.” Many had already led a nomadic existence, frequently moving in search of a better quality of life. Their forced relocation from San Juan Hill was another challenge they had to meet.

They persevered through this latest crisis, as they had done countless times before, with varying results, to address other hardships. Japanese immigrants who were civilian workers for the US Navy had lost their jobs at the Brooklyn Navy Yard because of new regulations that prohibited the employment of non-citizens. Both economic factors and private racial segregation limited where they could reside, adding to the burden of moving. Issei and nisei college graduates found securing professional employment difficult, if not impossible – with few exceptions, such as in the healthcare sector, in certain government jobs, or with Japanese companies – because of racial discrimination. Small business entrepreneurs encountered financing difficulties. American banks routinely declined to approve commercial or home loans for persons of Japanese ancestry. During World War II, Japanese New Yorkers, including American citizens, were subjected to employment termination, warrantless searches of their homes and businesses, FBI surveillance, and incarceration by the federal government without criminal charges or convictions.

By the time of their relocation from West 65th Street during the late 1950s, the majority of lodgers in the Ichiriki, Taiyo, and Matsuura rooming houses were middle-aged and elderly bachelors. Most had meager financial resources, and no immediate family members living nearby. Many of them would soon experience serious illnesses and disabilities. Although medical providers, government agencies, community organizations, such as the Japanese American Association of New York, and friends provided assistance, they would once again have to rely principally on themselves during the twilight of their lives.

Notes

1. Mitziko Sawada, Tokyo Life, New York Dreams: Urban Japanese Visions of America, 1890–1924 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 190; Glenn Collins, “Who Put the Lincoln in Lincoln Center? Good Question,” New York Times, May 12, 2009, C3; “Another Shubert Theatre,” New York Times, July 27, 1906, 7; “No Play at Lincoln Square,” New York Times, January 13, 1907, 9.

2. Daniel H. Inouye, Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 1876–1930s (Louisville: University Press of Colorado, 2018), 4–6, 35, 135, 139, 149; cf. Lon Kurashige, Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival, 1934–1990 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 7, 89–95; Andrea Geiger, Subverting Exclusion: Transpacific Encounters with Race, Caste, and Borders, 1885–1928 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 10, 47–49, 71.

3. Inouye, 138–45, 150–53, 179; Eleanor Walther Gluck, “An Ecological Study of the Japanese in New York City” (MA thesis, Columbia University, 1940).

4. Richard F. Shepard, “Memories of My Queens,” New York Times, September 3, 1995, CY 10; Inouye, 123–24, 149–50, 153, 270–71; Sawada, 22.

5. Inouye, 152–53, 174–79, 184; “US City Directories, 1822–1995,” New York, New York, s.v. “Masaichi Mukaitani,” 1933, Ancestry.com; 1940 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Ryuichi Murakami,” Ancestry.com; “US World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” s.v. “Uzaemon Tahara,” Ancestry.com; 1940 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Uzaemon Tahara,” Ancestry.com; New York Japanese American Directory, 1948–1949 (New York: Japanese American News Corporation, 1948), 2; 1950 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Uzaemon Tahara,” Ancestry.com; Robin D.G. Kelley, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (New York: Free Press, 2009), 15–22, 31; Monroe Berger, Edward Berger, and James Patrick, Benny Carter: A Life in American Music, vol. 1, 2d ed. (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2001), 8–13; Lorrin Thomas, “Displacement and Survival in Puerto Rican New York: Broken Promises in Lincoln Square,” January 30, 2023, Legacies of San Juan Hill, Lincoln Center, https://lincolncenter.org/feature/legacies-of-san-juan-hill/displacement-andsurvival-in-puerto-rican-new-york-broken-promises-in-lincoln-square.

6. Inouye, 183–84, 202.

7. Ibid., 105–6, 171.

8. Ibid., 179–81; Japanese-American Universities Quarterly 1 (July 1929); Ichiro Murase, telephone interview by Chiyo-ko Miyabara, July 5, 1991; “US World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918,” s.v. “Kuro Murase,” September 12, 1918, Ancestry.com; 1920 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Kuro Murase,” Ancestry.com; “US City Directories, 1822–1995,” New York, New York, s.v. “Kuro Murase,” 1922, Ancestry.com; “Antique Dealer Leases Madison Av. Building,” New York Times, April 23, 1926, 36; Yeiichi Kuwayama, interview by author, Washington, DC, June 8, 2002; “US World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” s.v. “Kuro Murase,” Ancestry.com.

9. Murase interview; “US WWII Japanese Americans Incarcerated in Confinement Sites,” s.v. “Kuro Murase,”Ancestry.com.

10. Roger Daniels, Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), 26–27, 33, 46–47, 53–61; Ozawa v. United States, 260 U.S. 178 (1922).

11. Misayo (Mitzi) Tsuji, interview by author, College Point, New York, October 24, 2003; “Japanese Business Directory in New York,” Japanese-American Commercial Weekly, July 19, 1919, 11; 1920 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Kaijiro Tanaka,” Ancestry.com; New York Japanese American Directory, 1948–1949, 2, 22.

12. Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283, 292–93 (1944) (citing War Relocation Authority Handbook of July 20, 1943 (Administrative Handbook on Issuance of Leave), § 60.4.3); Nanette Dembitz, “Racial Discrimination and the Military Judgment: The Supreme Court’s Korematsu and Endo Decisions,” Columbia Law Review 45, no. 2 (1945):

13. US Department of the Interior, War Agency Liquidation Unit, People in Motion: The Postwar Adjustment of the Evacuated Japanese Americans (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1947), 159–61; Daniels, 81–82; “Relocation House Set for Japanese,” New York Times, April 19, 1944, 10; Kimi Matsuda, interview by author, Honolulu, Hawai’i, January 24, 2004; Yuri Kochiyama, interview by author, New York, New York, March 21, 1999.

14. Yuri Nakahara Kochiyama, Passing It On – A Memoir (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2004), 12–15, 29–32, 39–45, 67–78, 117–21, 127–47; “32,808 Apartments Planned by City,” New York Times, February 1, 1948, 15; Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 95, 103–4; William Yardley, “Yuri Kochiyama, 93, Civil Rights Activist,” New York Times, June 5, 2014, B19; “Bill Kochiyama, Human Rights Activist, Dead at 72,” New York Amsterdam News, November 6, 1993, 26.

15. New York Japanese American Directory, 1948–1949, 2, B8; 1950 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Diana Usami,” Ancestry.com; “Matsushita-Hatasaki,” Hanford Morning Journal, April 9, 1942, 4; “US Final Accountability Rosters of Evacuees at Relocation Centers, 1942– 1946,” Jerome, Arkansas, June 1944, s.v. “David Matsushita,” “Kimiko Mae [sic] Matsushita,” and Ken [sic] David Matsushita, Jr.,” Ancestry.com; “US Final Accountability Rosters of Evacuees at Relocation Centers, 1942–1946,” Gila River, Arizona, November 1945, s.v. “David Den Matsushita,” “Mae Kimiko Matsushita,” “David Den Matsushita, Jr.,” and “Richard Ken Matsushita,” Ancestry.com.

16. 323 U.S. 283 (1944).

17. Ibid., 302–6; Lawrence E. Davies, “Ban on Japanese Lifted on Coast,” New York Times, December 18, 1944, 1; Peter Irons, Justice at War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 276–77.

18. 1940 US Census, Hanford, California, s.v. “Mae Hatasaki” and David D. Matsushita,” Ancestry.com; “California, US, Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882–1959,” Kobe, Japan, Taiyo Maru, March 27, 1934, s.v. “David Matsushita,” Ancestry.com; “California, U.S., Voter Registrations, 1900–1968,” Hanford Precinct No. 9, general election, 1938, s.v. “David Matsushita,” Ancestry.com; ”US Final Accountability Rosters of Evacuees at Relocation Centers, 1942–1946,” Gila River, Arizona, November 1945; 1950 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “David Matsushita,” “Mae K. Matsushita,” “David D. Matsushita, Jr.,” and “Richard K. Matsushita,” Ancestry.com.

19. New York Japanese American Directory, 1948–1949, 2; 1950 US Census, New York, New York, s.v. “Kokichi Tanaka,” Ancestry.com; “Yoshino-Ya,” Nisei Weekender, July 4, 1946, 3.

20. New York Japanese American Directory, 1948–1949, 1, A-12; “US World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” s.v. “Ishizo Tanaka,” Ancestry.com; “US Index to Petitions for Naturalization filed in New York City, 1792–1989,” s.v. “Ishizo Tanaka,” petition no. 8012998, naturalization certificate issued March 17, 1958, Ancestry.com.

21. Paul Crowell, “Lincoln Sq. Plan Wins Final Vote for Early Start,” New York Times, November 27, 1957, 1; Charles Grutzner, “City Plan Agency Backs Lincoln Sq.,” New York Times, October 3, 1957, 31; Keith Williams, “F. Y. I.,” New York Times, December 24, 2017, WE 3; Robert A. Caro, “The Power Broker, III – How Things Get Done,” New Yorker, August 12, 1974, 59.

22. Ross Parmenter, “Mrs. Kennedy to Be at Philharmonic Hall Opening,” New York Times, September 20, 1962, 28; Milton Esterow, “State’s Theater Opens at Center,” New York Times, April 24, 1964, 24; “Library-Museum of the Arts Opens at Lincoln Center,” New York Times, December 1, 1965, 55; Theodore Strongin, “Metropolitan Opera Shows Off Its New Home at Lincoln Center,” New York Times, March 23, 1966, 1; Russell Porter, “Robert Kennedy Hails Lincoln Sq.,” New York Times, November 19, 1961, 80; Joseph P. Fried, “‘College Town’ Is Rising on Fringes of Lincoln Center,” New York Times, December 4, 1967, 49, 52; “33 Ordered Evicted at Arts Center Site,” New York Times, June 18, 1959, 25; Donal Henahan, “Lincoln Center Fanfare for Park and Band Shell,” New York Times, May 23, 1969, 36; George Gent, “Juilliard Dedication Marks Completion of Lincoln Center,” New York Times, October 27, 1969, 1; Alan M. Kriegsman, “Juilliard Theater Debut,” Washington Post, April 25, 1970, E1; Irving Kolodin, “Fifty Years of Juilliard,” Juilliard News Bulletin 8 (1969), 44–45, 48.

23. Paul Crowell, “Lincoln Sq. Rivals Clash at Hearing Before Planners,” New York Times, September 12, 1957, 1; Glenn Fowler, “Lincoln Sq. Area Is Still Building,” New York Times, February 28, 1965, R1; Bernard Weinraub, “A Neighborhood Grows at Lincoln Square,” New York Times, January 22, 1965, 15; Charles Grutzner, “Work Is Speeded on Red Cross Site,” New York Times, February 18, 1959, 26; Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 158; Glenn Fowler, “The Impact of Lincoln Center: The Slums Around the Performing Arts Complex Are Slowly Giving Ground,” New York Times, September 15, 1966, 45; Robin Pogrebin, “City Opera Is in Talks for New Home,” New York Times, October 29, 2004, B1.

24. “Foes Draw Petition on Lincoln Square,” New York Times, February 14, 1957, 9; “Lincoln Sq. Rally Held,” New York Times, May 10, 1957, 38; Charles Grutzner, “Lincoln Sq. Plan Upheld as Legal by Appeals Court,” New York Times, May 2, 1958, 1; Anthony Lewis, “Lincoln Sq. Plans Wins Clearance in Supreme Court,” New York Times, June 10, 1958, 1; Charles Grutzner, “Wreckers Start Lincoln Sq. Job,” New York Times, July 29, 1958, 25; Williams, WE 3; Zipp, 240; Site Occupation Records, 1958–1960, Braislin, Porter and Wheelock Collection, Digital Archives, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts Archives, https://archives.lincolncenter.org/. As historian Samuel Zipp has summarized, “Moses’s people counted 6,018 families to be relocated [from the entire Lincoln Square site], while the tenant groups put the number closer to 7,000. The official number included only a partial count of the 4,507 dwelling units in 97 rooming houses, because the CSC’s [Committee on Slum Clearance] real estate firm judged that they sheltered only 750 ‘cohesive families’ requiring relocation under the law. The absolute number of people living on the 48-acre site, while difficult to know for certain, was more than 13,000 and possibly as high as 15,000.” Zipp, 219.

25. Lorrin Thomas, Puerto Rican Citizen: History and Political Identity in Twentieth-Century New York City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 193; Housing Act of 1949, Pub. L. No. 81-171, 63 Stat. 413, tit. 1, § 105(c) (stating “There be a feasible method for the temporary relocation of families displaced from the project area, and that there are or are being provided, in the project area or in other areas not generally less desirable in regard to public utilities and public and commercial facilities and at rents or prices within the financial means of the families displaced from the project area, decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings equal in number to the number of and available to such displaced families and reasonably accessible to their places of employment.”); Barbara Reach, “Relocation of Residential Site Tenants in New York City with Special Reference to Title I of the Housing Act of 1949: A Report and Recommendations” (New York: Committee on Housing, Community Service Society of New York, 1956), 3 (stating “The developer purchases the land from the City as it stands, including all buildings. Under a contract of sale, the City delegates to him its responsibility under the Federal law for relocating the residential tenants. (There is no obligation to assist commercial tenants in relocating). New York City is alone in following this procedure: in all other cities the local government handles relocation and demolition of site structures directly, before the vacated and improved land is conveyed to a developer.”) (emphasis in original); Zipp, 162.

26. Site Occupation Records, 1958–1960, Braislin, Porter and Wheelock Collection; “US City Directories, 1822–1995,” New York, New York, s.v. “David Matsushita,” 1960, com.

27. Tsuji interview; US World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” s.v. “Kazuo Nakayama,” Ancestry.com; “US City Directories, 1822–1995,” New York, New York, s.v. “Kazuo Nakayama,” 1960, Ancestry.com.

28. Robin Pogrebin, “Film Society Chooses Executive Director,” New York Times, July 17, 2008, E1, E5; Milton Esterow, “Beaumont Theater Opens at Lincoln Center,” New York Times, October 13, 1965, 1; Howard Taubman, “Juilliard Emerging Amid the Plaster Dust,” New York Times, December 20, 1968, 66.

29. Allan Kozinn, “Honoring Bernstein: Just Count the Ways,” New York Times, August 30, 1993, C13; Donal Henahan, “Bernstein Given a Hero’s Farewell,” New York Times, May 19, 1969, 54.

30. Pogrebin, “Film Society Chooses Executive Director”; William Grimes, “Lincoln Center Gallops to the Rescue of the Art Film,” New York Times, December 3, 1991, C 15; Steve Dollar, “Lincoln Center Hits Its Mark,” Wall Street Journal, June 10, 2011, A17, A23; Larry Rohter, “Poised for Releases: Two New Screens at Lincoln Center,” New York Times, April 5, 2011, C1; “Lincoln Ristorante,” Esquire, October 10, 2011, https://www.esquire.com/food-drink/ restaurants/reviews/a11157/lincoln-ristorante-new-york-1111/.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Anonymous. “The Life Story of a Japanese Servant.” In The Life Stories of Undistinguished Americans, as Told by Themselves, edited by Hamilton Holt, 159–73, 1906. Reprint, New York: Routledge, 2000.

Inouye, Daniel H. Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 1876– 1930s. Louisville: University Press of Colorado, 2018.

Sawada, Mitziko. Tokyo Life, New York Dreams: Urban Japanese Visions of America, 1890– 1924. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.