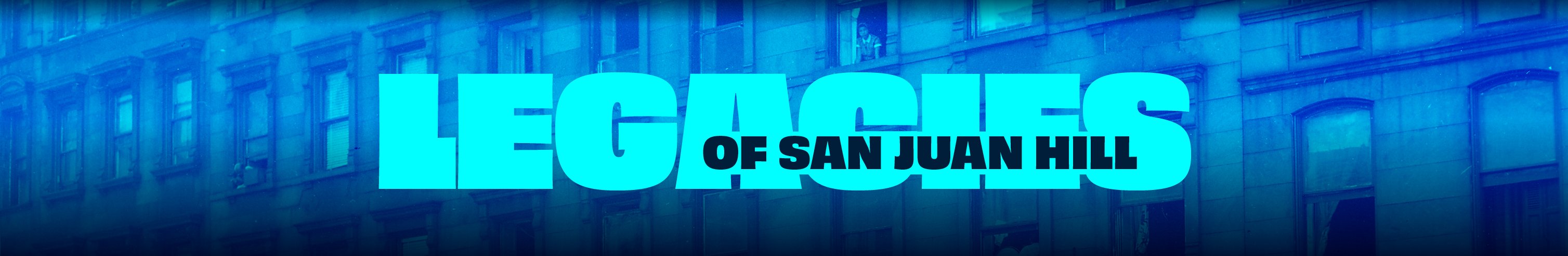

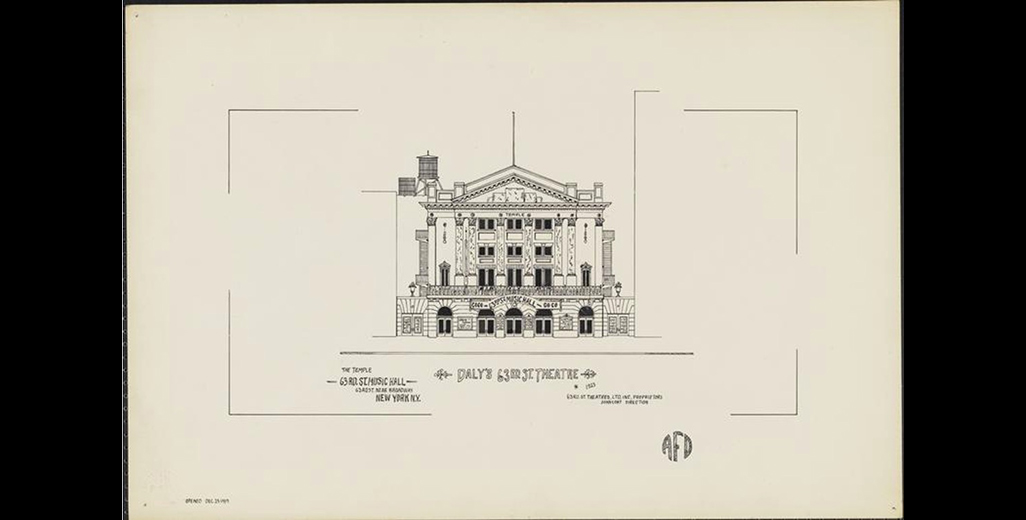

Architectural elevation of Daly’s 63rd Street Theatre

Museum of the City of New York

San Juan Hill’s Artistic Landscape

San Juan Hill’s Artistic Landscape

September 26, 2023

by Jessica Larson, Doctoral Candidate in Art History, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York

San Juan Hill was a site of enormous artistic output and innovation in the first decades of the 20th century. For Black musicians like Thelonious Monk or Benny Carter, the cultural landscape was a determining force in the formative years of their artistic development. For many in the neighborhood, including Black religious leaders, childcare and housing reform advocates, and other social progressives bent on racial uplift through the legitimation of Black expression, funding and promoting Black artistic achievements bolstered larger efforts for racial progress. Further, white reformers and philanthropists who intervened in San Juan Hill, such as Mary White Ovington and Henry Phipps Jr., adhered to the politics of respectability in believing that enforcing cultural ideals would help assimilate Black residents to the expectations of white American life. In many arenas, the later proliferation of artistic experimentation in Harlem found its roots in San Juan Hill.1

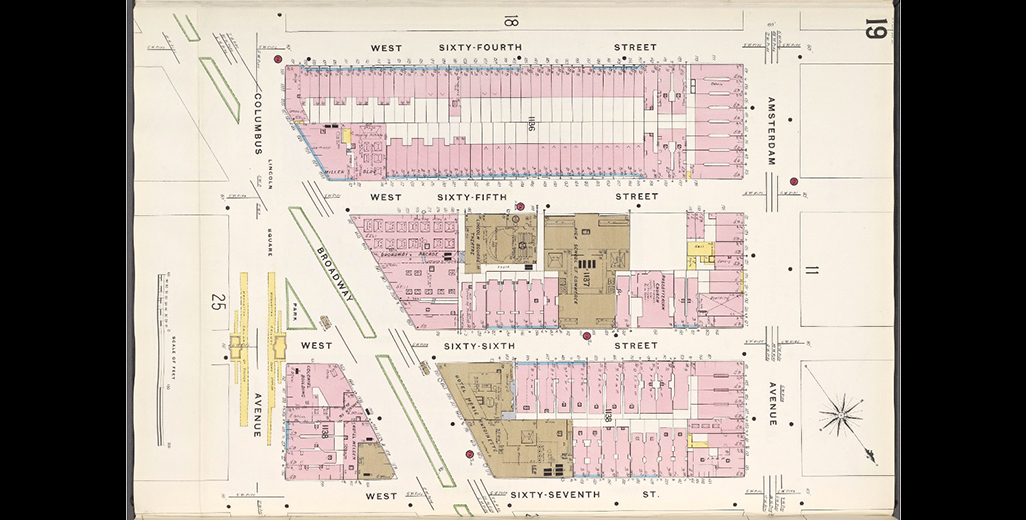

For white artists and performers too, the comparably low rents and relatively undeveloped built environment of San Juan Hill offered a site ripe for creative production. As the neighborhood’s population swelled and Manhattan residents began to migrate northward, entertainment venues began to fill the area west of Broadway in the West 50s and 60s to keep pace with emerging technologies like movie theaters.2 What resulted was a neighborhood filled with complex social and racial relationships, wherein the artistic life of San Juan Hill brought otherwise disparate groups into closer contact than arguably any other area of the city.

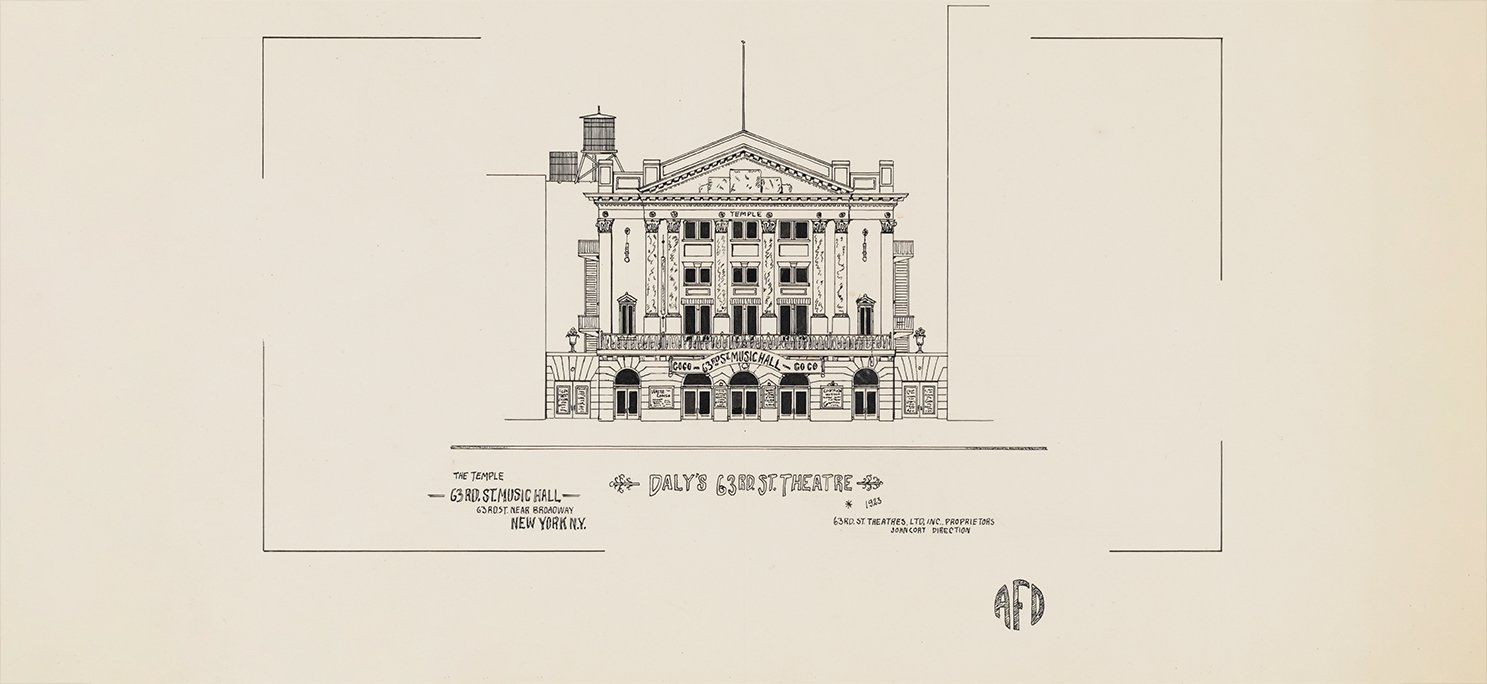

One of the most significant landmarks to this exchange was the Lincoln Arcade (or Lincoln Square Arcade). Built in 1903 and designed by architect and German immigrant Julius Munckwitz, this massive brick complex spanned the blocks between West 65th and West 66th Streets on Broadway. The completed structure was divided into two separate buildings, each six stories and a basement, wherein enclosed bridges connected the two buildings. Initially called the “Broadway Arcade” by the building’s creator, John L. Miller, this ambitious structure was envisioned as a site that could cater to the interests of local businesses, real estate developers, and the burgeoning entertainment scene on the West Side3. Though such mixed-use structures are commonplace today, this was a relatively new concept at the turn-of-the-century as developers sought to accommodate the financial demands of the newly booming metropolis.

While lower Manhattan was rapidly modernizing in tandem with mounting immigration from Europe by the end of the nineteenth century, San Juan Hill was not as fully developed. In 1900, most residents were still white, though that was quickly changing, particularly along streets between West 60th and West 63rd Streets, which would remain predominantly Black for the next several decades. However, Amsterdam Avenue was generally considered the dividing line between the white and Black sections of the area, with white residents living to the east of the avenue. One map, created by pioneering Black sociologist George Edmund Haynes in 1912, illustrated this breakdown of neighborhood racial composition. By Haynes’s research, supported by census data, the Lincoln Arcade’s location would have been segregated away from most Black residents of San Juan Hill, but close enough in proximity to where white residents surely would have encountered them in their daily lives.4 Of such tenants of the Lincoln Arcade were artists George Bellows and Robert Henri, two of the most formative members of the Ashcan School. The Ashcan School was an artistic movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries based in New York City, wherein artists turned their attention to the everyday inhabitants of the city, particularly immigrants and the working-classes, and the changing urban landscape. Bellows and Henri, alongside John Sloan, who frequently visited the Lincoln Arcade studios, were some of the most consequential artists in this circle, as well as the few who included Black figures in their works.5

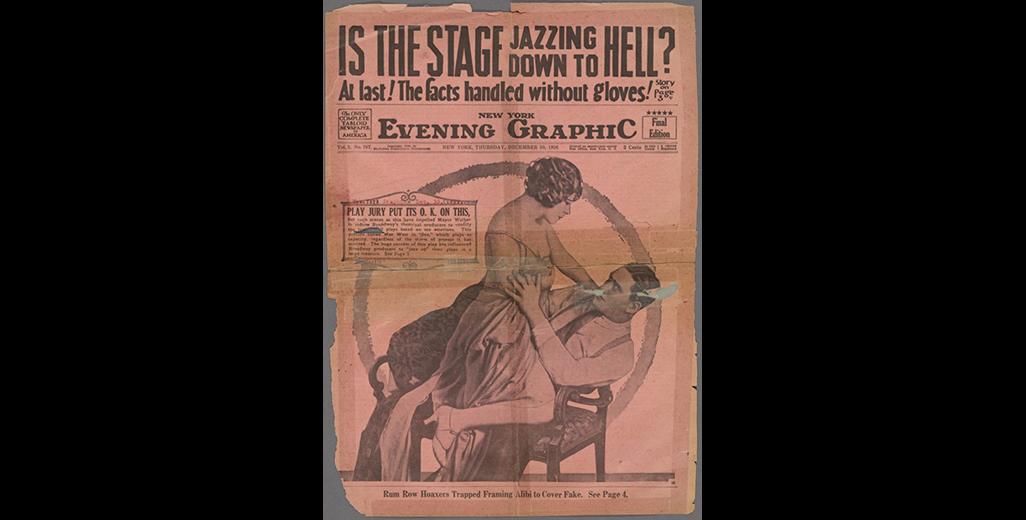

It was in San Juan Hill that Bellows painted one of the most impactful works of American Modernism, Both Members of this Club (1909). An interracial scene showing a tense standoff between two prizefighters, Bellows observed such fights at an athletic club across from the Lincoln Arcade on West 66th Street, called Tom Sharkey’s Boxing Club. The title referred to the practice of incorporating boxers as “club members'' in an effort to skirt legislation that prohibited public prizefighting. As such, Tom Sharkey’s garnered a reputation as a center for seedy, illicit underground activity, an assumption reinforced by, as Bellows so prominently depicted, the allowance of interracial patrons.6 Though state laws officially prohibited segregation in entertainment venues, the reality was that either outright or de facto segregation was commonplace; interracial saloons, referred to as “black and tans,” were sites vigorously condemned by the city’s reformers and were specific targets of police harassment.7 For Bellows, the proximity of this venue to his studio in the Lincoln Arcade facilitated his interest in artistically engaging with issues of race, a subject many of his contemporaries ignored. Further, while most Ashcan artists focused their attention on scenes in Lower Manhattan, Bellows’s numerous prints and paintings of Tom Sharkey’s acknowledged the place of neighborhoods like San Juan Hill as a part of the rapid march of modernity overtaking Manhattan’s urban landscapes.

Bellows and Henri were far from the only significant modernists who worked out of the Lincoln Arcade. In 1910, Bellows shared an apartment in the building with playwright Eugene O’Neill, who set his 1914 play “Bread and Butter” there.8 Among other prominent artists for whom the Lincoln Arcade served as a creative incubator included Milton Avery, Marcel Duchamp, Thomas Hart Benton, and Stuart Davis.9 The building’s design encouraged such work; constructed using techniques drawn from emerging industrial design practices, the structure incorporated large skylights and windows that well-served artists dependent upon heavy natural lighting. At times, this feature impacted artistic production; as Duchamp slowly created his work Large Glass (sometimes referred to as The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even), which he repeatedly returned to over an eight-year span, dust billowing in from Broadway coated the surface of the glass. Fellow Dadaist Man Ray photographed the work, titling the resultant photograph Dust Breeding (1920) and Duchamp later varnished portions of the dust onto the glass, embedding the impact of the artists’ built environment onto the picture plane.10

While many tenants of the Lincoln Arcade were professional artists, the building was not marketed specifically as a place intended to foster artistic expression. Rather, the large complex was broadly intended as a site meant to profit from the growing demand for entertainment venues as the city’s population of young residents with some degree of disposable income grew. By 1915, the area including and surrounding the Lincoln Arcade was hailed as “unquestionably a strong amusement center,” with real estate fetching some of the highest prices for speculative development in the city.11 In 1906, Miller financed the construction of a large, four-story theater on the lots adjoining the Lincoln Square Arcade on West 66th Street. Designed by architect John B. McElfatrick, this impressive structure spanned six lots and could seat roughly 1,530 patrons in its main auditorium. Ownership passed to Charles E. Blaney in 1907, who renamed the building the Blaney's Lincoln Square Theater; this was short lived, however, and within a few years the venue was purchased by Marcus Loew and became the Loew’s Lincoln Square Theatre.12 The theater could be accessed through an entrance on Broadway that passed through the Arcade. Known primarily for its vaudeville performances, this venue boasted some of the most advanced safety features in building construction, including the world’s first “water curtain” (a precursor to fire sprinklers) and the city’s only steel and asbestos curtain. Ironically, the building was partially destroyed by fire in 1931 and was subsequently rebuilt as a television studio.13

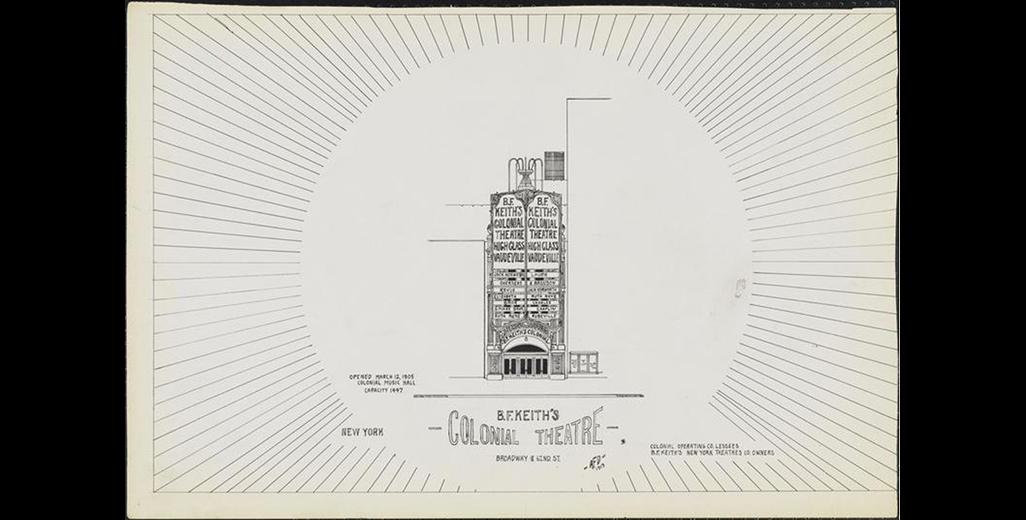

Loew’s was far from the only theater that capitalized on the growing entertainment district. A few blocks south of Loew’s, on Broadway and West 62nd Street, was the Colonial Theatre. Designed by architect George Keister and financed by Fred Thompson and Elmer Dundy, who were the masterminds behind Coney Island’s Luna Park, this venue opened in 1905 as a music hall, but quickly transitioned to prioritize vaudeville.14 Other performance sites in the area included the Century Opera House, Al Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre, the Park Theatre, the Circle Theatre, and many others.15 Together, these businesses helped construct an image of the area as a resort for New Yorkers throughout the city seeking to take advantage of the pleasures afforded by modern life.

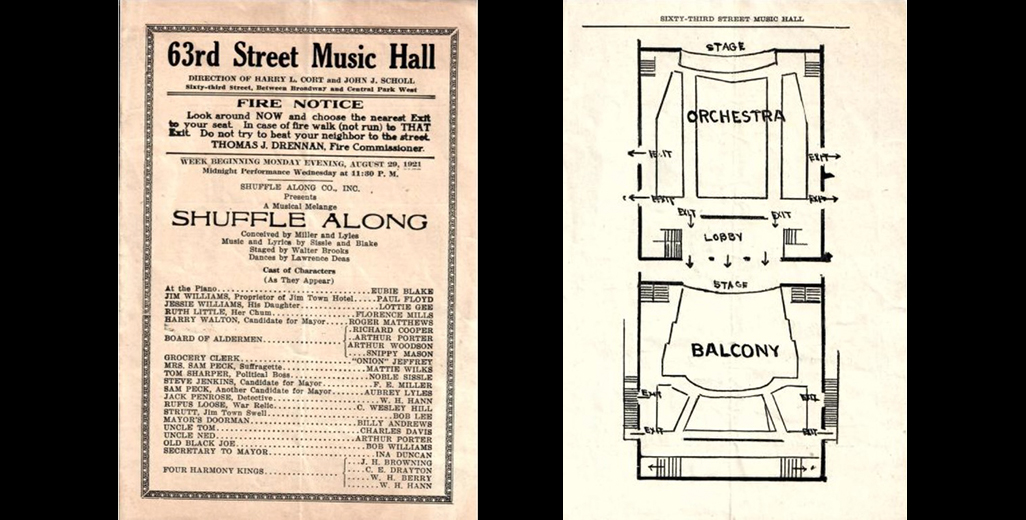

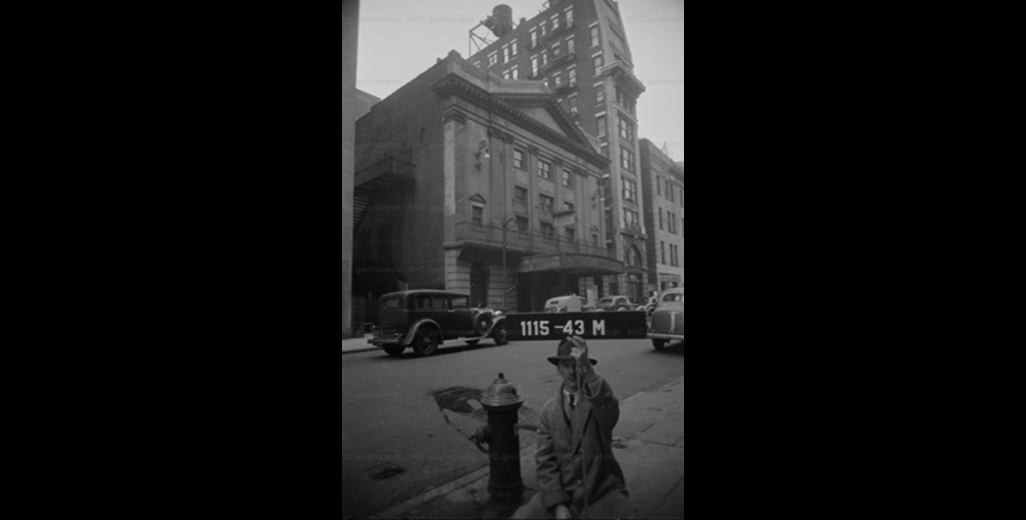

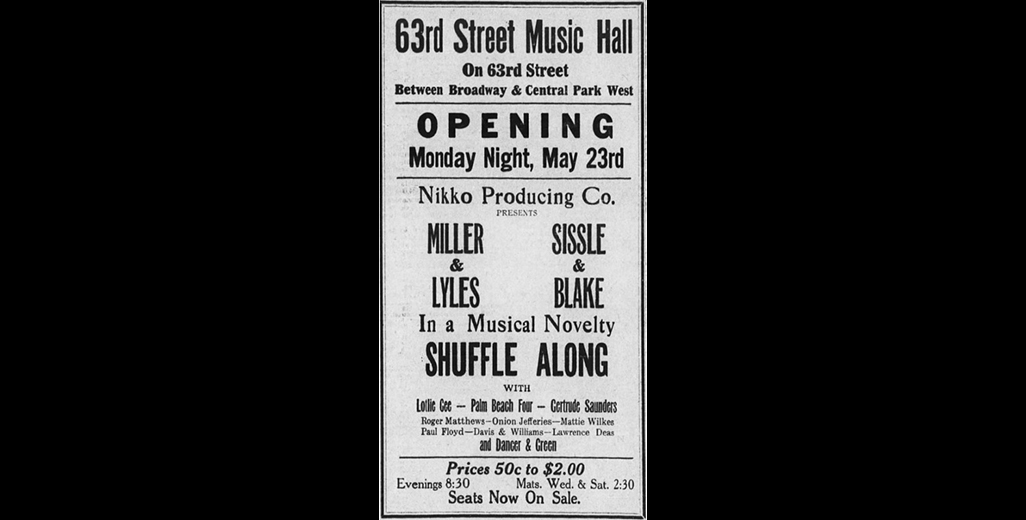

Possibly most famous, though, was the 63rd Street Music Hall at 22-28 West 63rd Street.16 Construction began in 1909 when the area’s entertainment scene was in full swing, though the structure’s original intention was markedly different from the surrounding cityscape. Built as a lecture hall for Christian youth, the venue was meant as a place for religiously-based lectures in the hopes that such services would uplift the moral character of the neighborhood. Ownership of the property changed hands several times, variously serving as a center for anti-Catholic agitation and a screening space for children’s films; in 1921, however, the venue was subsumed into the modern spectacle of the area, becoming solely dedicated to performance theater in 1921.17 While this new theater was one of many that populated the east side of San Juan Hill, it was unique in that the productions chosen for the venue often engaged directly with the city’s changing racial landscape. The first play performed at the theater was Shuffle Along, a musical written and performed entirely by Black entertainers. Though other theaters in the area had previously featured productions that, in some form, acknowledged complicated racial dynamics, Shuffle Along was the first major production to be entirely the product of Black creativity. An enormously popular show, the musical helped launch the careers of Josephine Baker and Florence Mills and ran for an astounding 504 performances at the West 63rd Street theater.18 The success of the show can be attributed in part to its siting in San Juan Hill; the show had failed to secure a venue on Broadway and resorted to the West 63rd Street, which was still widely considered a Black enclave, as evidenced by one write-up of the musical published in the New York Herald, titled “In Darkest 63rd Street.”19

As the West 63rd Street Music Hall was not purpose-built as a space for musical theater, the show’s organizers had to quickly adapt the venue to accommodate the ambitious project. The stage was enlarged and seating was removed to make room for the fourteen-piece orchestra required by Shuffle Along; some of these renovations were so urgent that they continued during the musical’s first few performances.20 Such less than ideal circumstances were indicative of broader challenges facing Black residents of San Juan Hill, who often had to adaptively reuse existing buildings for new purposes as white property owners refused to rent or sell to them. Nevertheless, the significance of siting the show in a predominantly Black area was not lost on either the musical’s writers or critics. One white critic with Variety wrote in his review “The 63rd Street Theatre is…a few blocks to the westward…[of] a negro section known as ‘San Juan Hill’…so that ‘Shuffle Along’ ought to get all the colored support there is, along with the white patrons who like that sort of entertainment.”21

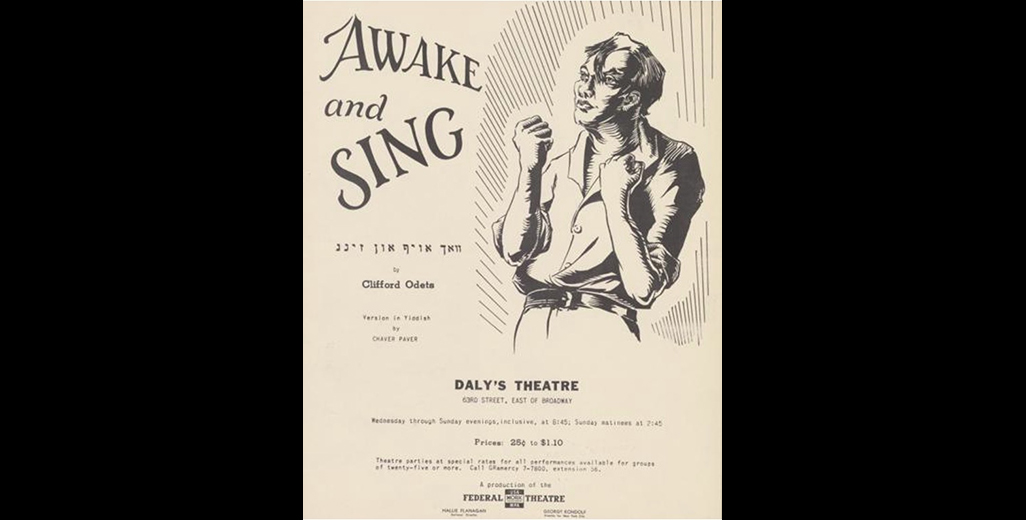

The West 63rd Street Music Hall’s production of Shuffle Along pushed the racial boundaries of Manhattan’s thriving entertainment scene beyond the stage. Called an “epoch-making” show by Black writer James Weldon Johnson, the seating for the musical was integrated. Black patrons were able to purchase tickets in the back rows of the theater, a rear section that comprised a third of the house; while not revolutionary by today’s standards, this was still an improvement over the standard practice of relegating Black theater-goers to balcony seats.22 Ownership of the 63rd Street Music Hall changed hands many times over the years, but continued to host productions that reflected the area’s progressive complexity. In 1936, the theater produced a play on the life of the radical abolitionist John Brown, titled Battle Hymn, which was much-lauded by the NAACP’s The Crisis; in 1938, reflecting the influx of Jewish residents that began to populate the Upper West Side in the 1930s, the theater hosted Awake and Sing!, a play entirely in Yiddish.23

The spectacular landscape of San Juan Hill underscored the porous nature of sites otherwise regarded as segregated. Entertainment venues, whether they were dedicated to performance, the visual arts, or sports, proved contested ground, wherein white and Black figures encountered the realities of each other’s lives. For Black creatives, many of these projects found success later in Harlem. While the construction of Lincoln Center, beginning in the 1950s, displaced many residents who had been vital to the artistic life of the neighborhood, the creation of the site continued a legacy of innovative expression that had been so integral to the originality of the neighborhood.

Notes

1 Robin D.G. Kelley, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (New York: Free Press, 2010), pp. 16-20.

1 Joseph J. Varga, Hell's Kitchen and the Battle for Urban Space: Class Struggle and Progressive Reform in New York City, 1894-1914 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2013), pp. 91-92; Shannon King, Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism During the New Negro Era (New York: NYU Press, 2017), pp. 28-29.

3 “The Building Department: List of Plans Filed for New Structures and Alterations,” New York Times (Jul. 1, 1902), p. 14; Christopher Gray, “The Story of a Name, the Tale of a Co-op,” New York Times (Oct. 2, 2005), p. 8.

4 George Edmund Haynes, The Negro at Work in New York City: A Study of Economic Progress (1912; repr., New York, 1968), pp. 486-452.

5 Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 197.

6 Marianne Doezema, George Bellows and Urban America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), pp. 75-82; Douglas J. Flowe, Uncontrollable Blackness: African American Men and Criminality in Jim Crow New York (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), pp. 60-61.

7 Robert Haywood, “George Bellows's "Stag at Sharkey's": Boxing, Violence, and Male Identity,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring, 1988), pp. 4-7.

8 Doris Alexander, Eugene O'Neill's Creative Struggle: The Decisive Decade, 1924-1933 (University College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992), pp. 59-60.

9 Gerry Souter, American Realism (New York: Parkstone Press International, 2012), p. 156.

10 Larry Witham, Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2013), p. 139.

11 Many Kinds of Buildings in Lincoln Square District,” New-York Tribune (Feb. 7, 1915), p. 33.

12 “C.E. Blaney Leases the Lincoln Square,” New York Times (May 3, 1907), p. 7; David L. Lightner, Winne Lightner: Tomboy of the Talkies (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), n.p.

13 “Big Broadway Fire Imperils Hundreds,” New York Times (Jan. 30, 1931), pp. 1, 4.

14 Nicholas Van Hoogstraten, Lost Broadway Theatres (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991), p. 91.

15 Julius Cahn and R. Victor Leighton, eds. The Cahn-Leighton Official Theatrical Guide, Vol. 16 (1912), p. 91.

16 This venue changed names many times over the years, including “The 63rd Street Music Hall,” “The Cort 63rd Street Theatre,” and “Daly's 63rd Street Theatre.” For the sake of consistency, I refer to it as the 63rd Street Music Hall.

17 Van Hoogstraten, 123; “Anti-Catholics Hold Peaceful Meeting, Guarded by Police,” New-York Tribune (May 3, 1920), p. 18.

18 Arnold Shaw, The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920’s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 88-91.

19 “In Darkest 63rd Street,” New York Herald (Jun. 26, 1921), p. 36.

20 Brian D. Valencia, “Musical of the Month: Shuffle Along,” The New York Public Library, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2012/02/10/musical-month-shuffle-along.

21 Quoted in: Richard Carlin and Ken Bloom, Eubie Blake: Rags, Rhythm, and Race (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 131.

22 Rudolph P. Byrd, ed., The Essential Writings of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Random House, 2008), p. 216.

23 Michael Blankfort, “John Brown Re-Created,” The Crisis, Vol. 43, No. 5 (May 1936), p. 143; “Stage News,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Jan. 20, 1939), p. 25.