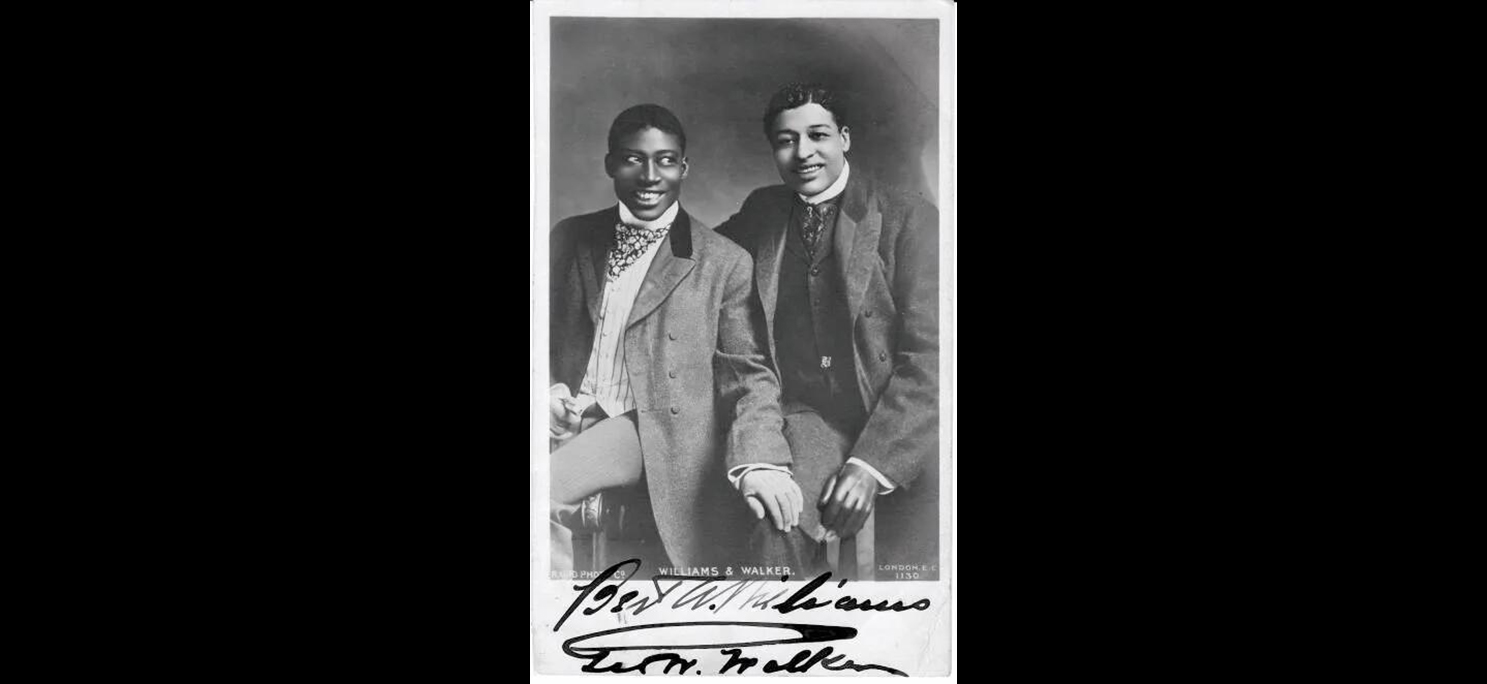

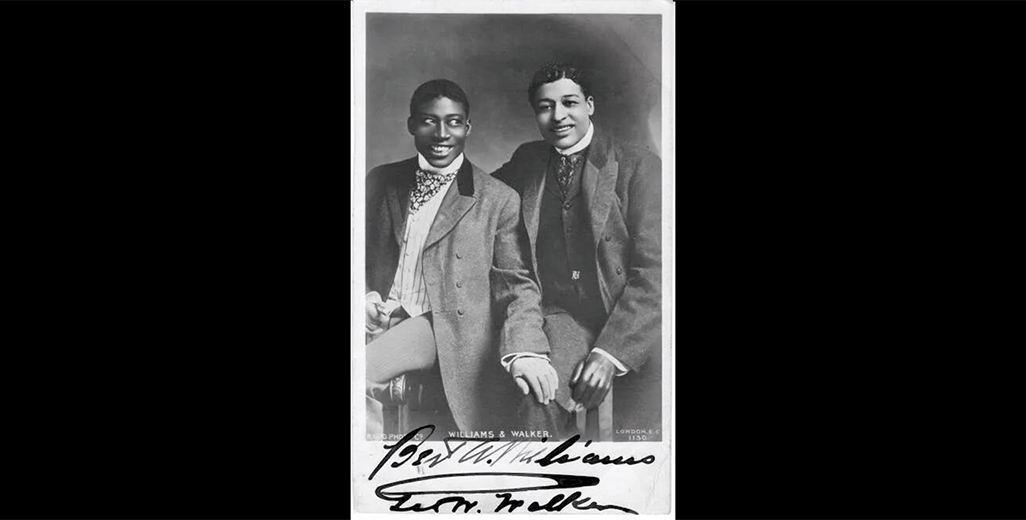

Williams and Walker autographed press photo, London, 1903.

Theatre Moves Uptown

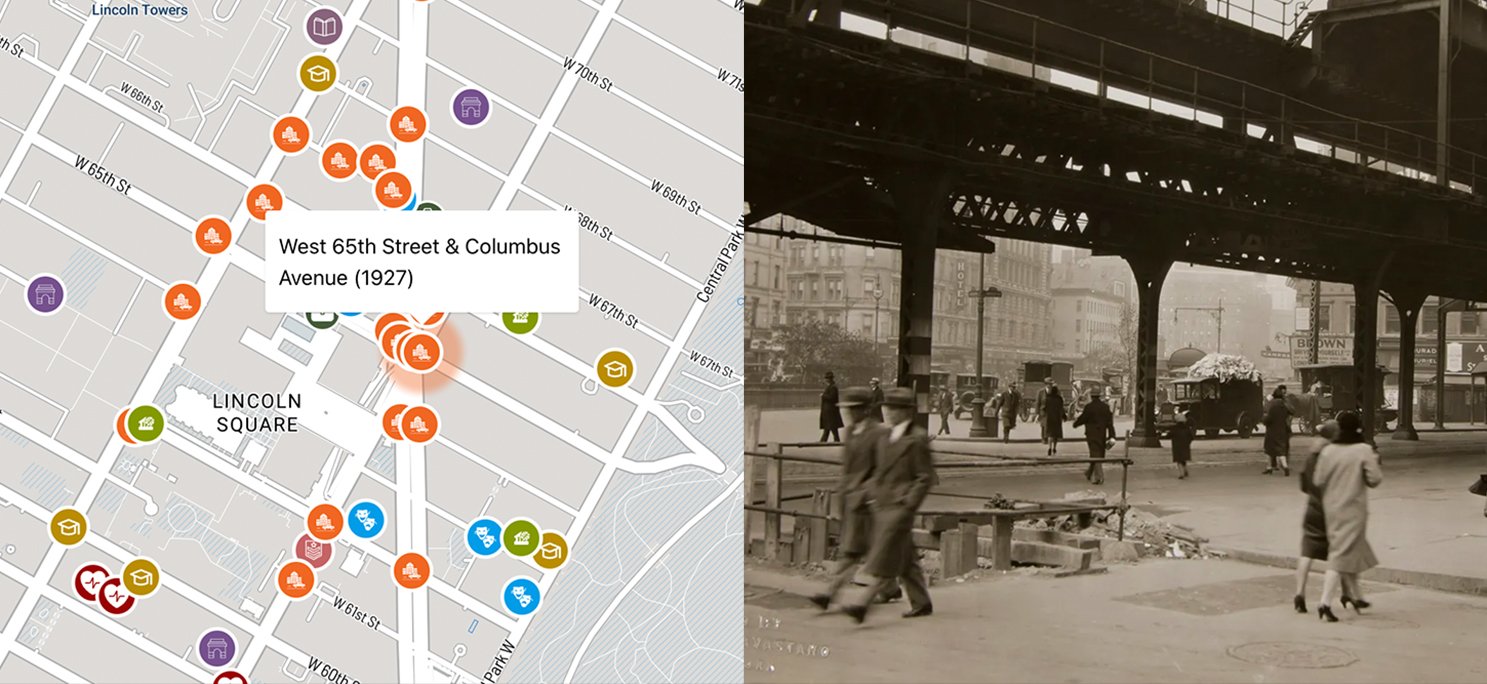

Built in 1903 on Columbus Circle at 59th and Broadway in New York City, the historic Majestic Theatre lasted less than a decade. Yet, it holds a place in theater history as the venue for some of the most influential works by Black musical theater companies, which were beginning to emerge at the turn of the 20th century. Notably, it served as the de facto Broadway “home” for the Williams and Walker Company.

Designed by architect John H. Duncan, whose previous New York works included the Grant Memorial, the Grand Army Plaza, and the Knox Building, the Majestic was the second theatre built in what was then known as Lincoln Square, or San Juan Hill, at 59th Street and 8th Avenue, right on Columbus Circle. At the time, Broadway theatres were centered several blocks south, in midtown, but the entertainment district was slowly expanding northward. Some speculated that 59th Street, in its position on the edge of Central Park, might be “the next logical center of the theatrical and night life of the metropolis.”1 Others were more skeptical:

Whether the Majestic Theatre is uncomfortably uptown depends entirely on the point of view. A Tottenville, S.I., young man escorting a Fordham girl to the theatre would probably find it a happy medium. Anyhow, it has flung the torch of enlightened gayety nearly a mile further toward the Connecticut frontier…..2

The proprietors, E.D. Stair and A.L. Wilbur, owned or controlled several theatres separately; Stair’s other partnership, Stair and Havlin, controlled a nation-wide series of “popular price” theatres (where the premium seats cost $1 or less), and early reports suggested that the Majestic would also be a popular price house. However, as the project drew nearer to completion, news reports clarified that the Majestic would be a “high price” theatre3 ("high price,” or “first-class” theatres boasted more elaborate production values, higher salaries for performers, and premium seat prices of $1.50 or $2).

The Majestic opened January 20, 1903, with a musical adaptation of Frank L. Baum’s Wizard of Oz. It was an auspicious opening for the theatre, the enthusiasm around the venue itself being somewhat more than the excitement around the play. One reporter declared, “It is become already one of the mid-city landmarks.”

The new playhouse is extremely comfortable, quite elaborate in its architectural and decorative schemes, and fireproof. There are no pillars in the house, two marble shafts in the rear not disturbing the vision… A sunburst electric chandelier lends a brilliant effect to the auditorium. Six tiers of boxes, elevators for the gallery and every convenience imaginable in the matter of the stage and dressing rooms make the Majestic a unique theatre. The drop curtain is a rich green. The dome of the building, with electric lights clustering over it, is easily distinguished as one approaches the city.4

Less than a month after the Majestic’s successful debut, another breakthrough event occurred several blocks south, as the Williams and Walker Company’s musical, In Dahomey, opened at the New York Theatre, marking the first full-length Broadway production of a play written and performed by an all-Black cast.

Williams and Walker Take Manhattan

George Walker and Bert Williams first met in San Francisco in the early 1890s. They performed together in a local minstrel troupe for several months before deciding to develop a vaudeville act together. In 1896, the pair arrived in New York and quickly became renowned on the vaudeville circuit. Still, Walker and Williams were eager to branch out and to become part of the small but growing community of Black artists based in the city. To that end, they rented an apartment on West 53rd Street, then the heart of Black Bohemia, and turned it into a gathering space for “all colored men who possessed theatrical and musical ability and ambition.”5 Amidst this group of artists, three companies emerged which would be known as the “triumvirate” of Black musical theater: the companies of comedian/songwriter Ernest Hogan, the Cole and Johnson Company, and the Williams and Walker Company.6 In addition to Williams and Walker themselves, the following artists were indispensable in the formation and success of the company: Jesse A. Shipp and Alex Rogers (book and lyrics writers who formed the “core four” of company leadership); Will Marion Cook, the classically-trained musician who provided the score for all their major works; Aida Overton Walker, the company’s chief dancer and choreographer—and one of the great performers of her day—who was also George’s wife; and performer Lottie Thompson Williams, Bert’s wife.

After a six-week run at the New York Theatre, the Williams and Walker Company brought In Dahomey overseas for a year-long tour of England and Scotland (where they were so well-received that the Company was invited to Buckingham Palace), then back to the States for a final season, which included two additional stints at New York’s Grand Opera House. Immediately after In Dahomey’s final bows in May 1905, Williams and Walker began preparing for their next production, Abyssinia, a piece that would build on the success of the previous season and surpass it, with a cast of 110 performers, a lush scenic design, and a musical score that allowed Will Marion Cook to show his classical composition talents as well as his and Williams’ brilliance for crafting songs. The story, rendered in Jesse Shipp’s book and Alex Rogers' lyrics, is a simple one:

The story tells the adventures of a party of colored tourists from Kansas, who reached Abyssinia en route to Jerusalem. Jasmine Jenkins (Bert A. Williams) and Rastus Johnson (George W. Walker) head the party. Both spend lavishly the money Rastus has won in the Louisville lottery. By mistake they are arrested by Menelik’s police because they resemble conspirators, and the complications that follow create the fun.7

In preparation for this production, the company took two actions early on, one artistic and one administrative. First, they founded the Williams and Walker Glee Club, an ensemble of younger company members chosen to tour and study during the off-season. Walker explained that the chorus would serve both to give the members profitable work during the offseason, as well to provide on-the-job training in both classic music and “Negro specialties” that would make up the vocal demands for the upcoming season.

In advance of the season, Williams and Walker also made the decision to part with their managers, Hurtig and Seamon, in favor of veteran minstrel and vaudeville star Lew Dockstader, who pledged to book Williams and Walker exclusively into first-class theatre houses and to advance $30,000 for the creation of the piece. Whatever the merits of making the change, this decision almost derailed their season. As the previous managers decided to fight the dismissal, Williams and Walker had to contend with a lawsuit; and though they prevailed, the release of their financials during the proceedings (it was revealed that the partners had earned $15,000 each the previous season) created some minor outrage. “This is more than the Chief Justice of the United States makes,” griped one paper.8

Later, the season faced greater jeopardy when Dockstader reneged on the agreement, preparing the company for popular price houses and offering one half of the $30,000 that Williams and Walker had already budgeted. Rather than agree to these new conditions, the company stopped rehearsals and pulled out of their agreement, breaking with their second manager in as many months. Williams and Walker took their act to vaudeville, under a short-term contract with Oscar Hammerstein. To keep the company from disbanding completely, it divided into three groups: Williams and Walker, the Glee Club, and the women of the company, who under the leadership of Aida Overton Walker were billed as the Abyssinian Maids.9

In December, the Company found a third manager, Melville B. Raymond. Raymond had a reputation for managing successful shows, but also for having shows run aground; taking him on was risky, but he may have been the best option for saving their season.10 Originally scheduled to be presented at the New York Theatre, as In Dahomey had been, the deal fell through—by some accounts, killed by A.L. Erlanger, the theatre’s manager and one half of the powerful theatre brokers, Klaw & Erlanger. Shortly after, Raymond arranged to book Abyssinia at the Majestic Theatre.

The Williams and Walker Company at the Majestic Theatre

By 1906, the Majestic’s “new theatre” glow had faded and the construction of several new houses in the Theatre District had cemented its status as a theatre in the hinterlands of Broadway. Still, it was a first-class house (though with top prices at $1.50 rather than $2), and—perhaps more importantly—it was not a Klaw-Erlanger house.

Abyssinia opened February 20, 1906. While Williams and Walker had intended to present Abyssinia to Broadway, they had not planned on a Broadway premiere, but to follow the approach they had employed with In Dahomey: a small tour in the fall to get the show in shape, then a Broadway run in the winter, followed by a proper national and/or international tour—possibly one lasting through two or three seasons. Having lost the fall to management crises, and with a truncated rehearsal period, Williams and Walker were bringing a work still very much in process to the Majestic stage.

Among the critics, there was near-universal agreement that the show needed trimming, and that the plot was thin. Aside from that, opinions varied greatly, not only about their own experience of the play but in their perceptions of the audience’s response. The New York Times critic proclaimed, “The piece is far in advance of their last vehicle…in costumes, scenery, and effects, while the work of the singers, especially in the choruses, surpasses all their previous efforts;” while the Sun declared it “a rather dreary jumble of dull lines and tuneless music." The New York Age, the city’s major Black newspaper, praised the work of the chorus and dancers, while the Buffalo Express insisted that—with the sole exception of Bert Williams in blackface—the piece lacked “negroism.” The Indianapolis Freeman critic, coming to visit later in the run, found that the cuts Raymond had imposed made the play feel smaller, both in cast and in beauty, and was disappointed that Williams and Walker had allowed it.11

Like many first-class theatres, the Majestic was segregated by section. Blacks were not allowed to purchase seats in the orchestra; however, they were not restricted to their sections at intermission—much to the chagrin of one reporter, who was horrified to find himself sharing lobby space with African Americans, and that “droves of negroes invaded the beautiful restaurant and cafe next door.” Not that they would be served there; the nearby hotels and restaurants did not serve Black patrons, a fact which, as the New York Tribune aptly noted, created an undue hardship for the Abyssinian company.

“It is safe to say,” predicted the Evening Sun reviewer, “ that it will be a long time before a theater of the Majestic's standing will try such an experiment again.” 12 In actuality, just two years passed before the Majestic once again hosted the Williams and Walker Company.

During that time, Williams and Walker had applied the lessons learned from Abyssinia to getting the company back in good standing. After legally untangling themselves from Melville B. Raymond (who had gone bankrupt yet again), they found a new manager, F. Ray Comstack, well in advance of the next season. Walker drew up a contract that stipulated that Comstack would push to keep the company in first-class theatres, would share managing interest with Williams and Walker, and would also cede sole control of the scripts, music, casting, and design to them. The contract also put Williams and Walker in relationship with the Shubert Brothers, who had officially purchased E.D. Stair’s interest in the Majestic shortly after Abyssinia closed.13

Their new play, Bandanna Land, was also a departure from Abyssinia, suggesting that Williams and Walker took the “not enough Negroism” critiques to heart. Instead of Black New Yorkers or African landscapes, the play is set in the early 20th-century contemporary South, featuring a character who wants to join a minstrel show. Book writers Jesse Shipp and Alex Rogers attempted to evoke the humor of minstrelsy without devolving into buffoonish stereotypes. And by all accounts, they succeeded greatly. As one critic put it:

The piece is naturally full of songs and dances for the principals and those are the things which arouse the white spectators to something like a fury of applause. The touches which portray the life and character of the ordinary negro arouse quick and hilarious laughter among the colored auditors, pretty good evidence that the authors and actors have told the truth.14

After successfully touring through the fall of 1907, Bandanna Land opened at the Majestic on February 3, 1908, to near-universal acclaim, and full, enthusiastic houses. Per Walker’s biographer, Daniel E. Atkinson, “The company earned $10,000 by the fifth week of the run, and more than ninety-three thousand people saw the show.”15 Its success cemented Williams and Walker as legitimate theatre makers able to fill first-class houses. It is important to note that Williams and Walker saw Broadway as a means to book first-class theatres around the country—both to give the company the respect they felt due to them, and also to make it possible to meet their production standards and their payroll costs, which at the time of Bandanna Land, Walker estimated to be $2,300 per week.16

On March 31, Williams and Walker held a gala event on the Majestic stage celebrating the sixteenth anniversary of their stage partnership. For the event, the theatre released the gallery as well as the balcony for Black patrons. According to New York Age critic Lester A. Walton, those upper seats were full two hours before the show started. After performing the first two acts of Bandanna Land, in place of the third act, Williams, Walker, Overton Walker, and the Chorus performed popular songs from their past shows, as well as songs from Williams and Walker’s earlier days together, including the first song they ever performed together.17

Bandanna Land was the Williams and Walker Company’s final play. During the second season, George Walker took ill, and in February 1909, he was forced to retire from the stage. Bert Williams attempted to run the company alone for a season, but that show (Mr. Lode of Koal, which also opened at the Majestic) was a financial failure without Walker’s business savvy, and Williams was forced to fold the company. 1909–10 also marked the deaths of Ernest Hogan and Bob Cole, effectively gutting the three most successful Black theatre organizations in New York. Walker died of paresis in 1911. Later that same year, Schubert and Wilbur would give up on the notion of legitimate theatre uptown; they leased the Majestic to Frank McKee and William Harris, who promptly renamed it the Park Theatre. It would be another decade before a Black musical would appear on a New York stage. That piece, Shuffle Along (which debuted at the 63rd Street Music Hall, a few blocks north in San Juan Hill), would become a Broadway hit—bringing Black musical theater into greater recognition and advancing the artistic legacy that Williams and Walker make strides in establishing.

Notes

1 “Shifting Theatre District,” New York Evening World, November 29, 1902, p. 9.

2 “Wizard of Oz Comes to Town,” New York Evening World, January 21, 1903, p. 7.

3 New York Times, November 23, 1902, p. 14.

4 “Theatre Majestic Opened,” New York Sun, January 21, 1903, p. 9.

5 George Walker, “The Real Coon on the American Stage,” The Theatre, August 1906, p. 224.

6 Lester A. Walton, “The Passing of the Triumvirate,” New York Age, October 10, 1910, p. 6.

7 “Notes of the Stage,” Brooklyn Daily Times, February 21, 1906, p. 4.

8 “Profits of Negro Comedy,” The New York Times, July 6, 1905, p. 9; “Rewards of Coon Comedy,” The Buffalo News, July 15, 1915, p. 5.

9 “Abyssinia May Not Appear,” New York Age, September 21, 1905, p. 1; “Abyssinia Postponed,” Colored American Magazine vol. 9, no. 5, November 1905, p. 607; New York Sun, October 4,1905, p. 5.

10 “Theatrical Manager Bankrupt,” New York Tribune, July 13, 1905, p. 5.

11 “Williams and Walker Again,” New York Times, February 21, 1906, p. 9; New York Sun, February 21, 1906, p. 8; “Abyssinia,” New York Age, February 22, 1906, p.1; Buffalo Courier Express, March 4, 1906, p. 44; Indianapolis Freeman, April 14, 1906, p. 6.

12 Evening Sun critic Acton Davies, quoted in The Sacramento Bee, March 3, 1906, p.19; New York Tribune, March 4, 1906, p. 7.

13 Camille F. Forbes, Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America’s First Black Star (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2008), p. 149.

14 “The Theaters,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 21, 1908, p. 26.

15 Daniel E. Atkinson, The Rediscovery of George Nash Walker: The Price of Black Stardom in Jim Crow America (New York: SUNY Press, 2025). Walker wanted the company to be seen and acknowledged as a Black institution, so getting consistently booked into first-class theatres was a must. The down side was that most of those theatres were also segregated and relegated Black audiences to the balcony sections. So, in addition to some white papers being appalled at the arrogance of Williams and Walker's insistence on being featured on the legitimate stage, some Black papers considered it neglecting their most loyal fan base.

16 George Walker, “Bert and Me and Them,” New York Age, December 24, 1908, p. 12.

17 Lester A. Walton, “Anniversary Celebration of Williams and Walker a Gala Event,” New York Age, April 2, 1908, p. 6.