W. 63rd Street and West End Avenue, near Lincoln Center's campus, is named in honor of Thelonious Monk

Photo by Al Bland

Recovering Legacies: How Thelonious Monk, Nina Simone, and the Musicians of San Juan Hill Made History at Lincoln Center

Recovering Legacies: How Thelonious Monk, Nina Simone, and the Musicians of San Juan Hill Made History at Lincoln Center

November 15, 2023

by Al Bland, Archival Researcher at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

This is a story about a changing neighborhood. The catalyst for the change, urban renewal, altered the built environment and composition of an historic neighborhood on Manhattan’s upper west side, before and after the construction of Lincoln Center. But counter to many narratives, Black artistic life in the area lived on.

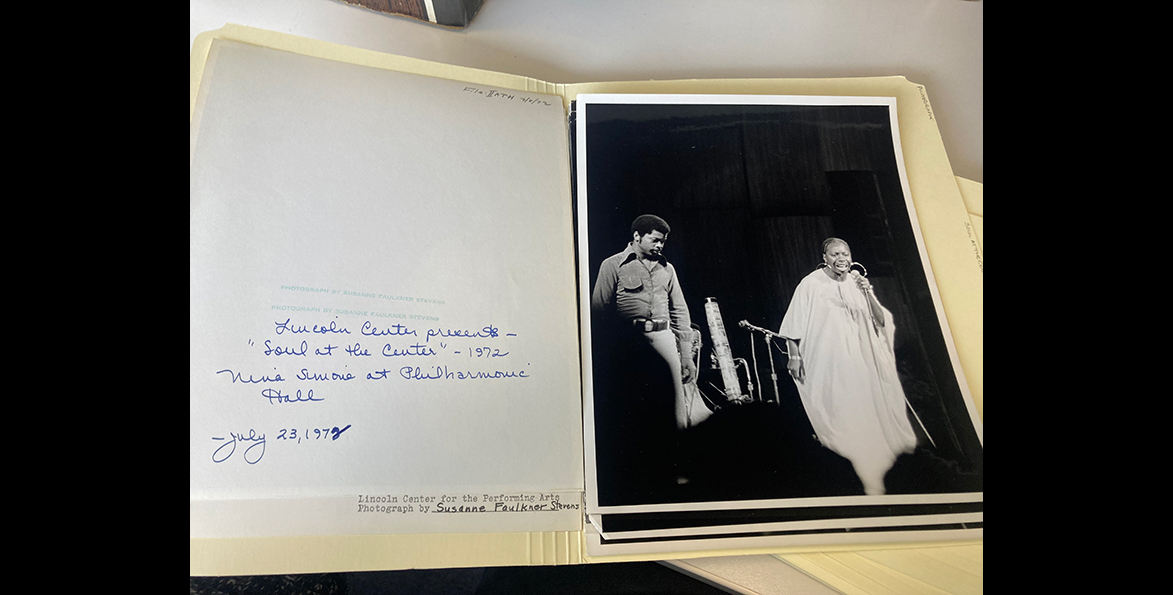

Thelonious Monk lived in San Juan Hill, and remained in the area as it became more widely known as Lincoln Square. Nina Simone moved to the area in the early 1970s, a time when the neighborhood looked far more new than old. In the period these musicians lived near Lincoln Center, they achieved significant career milestones on its stages. These two iconoclastic pianists are now among the major influences of performers and students at Lincoln Center.

As we honor them today, we can also connect their legacies to many of the first Black pianists of New York City to earn acclaim, a number of whom named San Juan Hill as a place they lived, performed, and socialized.

Monk Encounters Legacy

Thelonious Monk's San Juan Hill was a place of encountering legacy, expanding it, and inventing something new altogether.

The first generation of "Harlem Stride" pianists lived in San Juan Hill. Stride pianists were notorious among the "surprising amount of musicians", in the words of historian and Monk biographer Robin D.G. Kelley, who called the neighborhood home either literally or figuratively, making their living as house pianists in the tenement dives and dancing clubs of San Juan Hill.

As Marcy Sacks and other historians have richly conveyed, before Harlem, most Black New Yorkers lived in and around San Juan Hill. Musicians were no exception to that. Perhaps because San Juan Hill’s history is not widely known, some achievements of early Black New York have been placed in Harlem that also spanned San Juan Hill or took course there entirely.

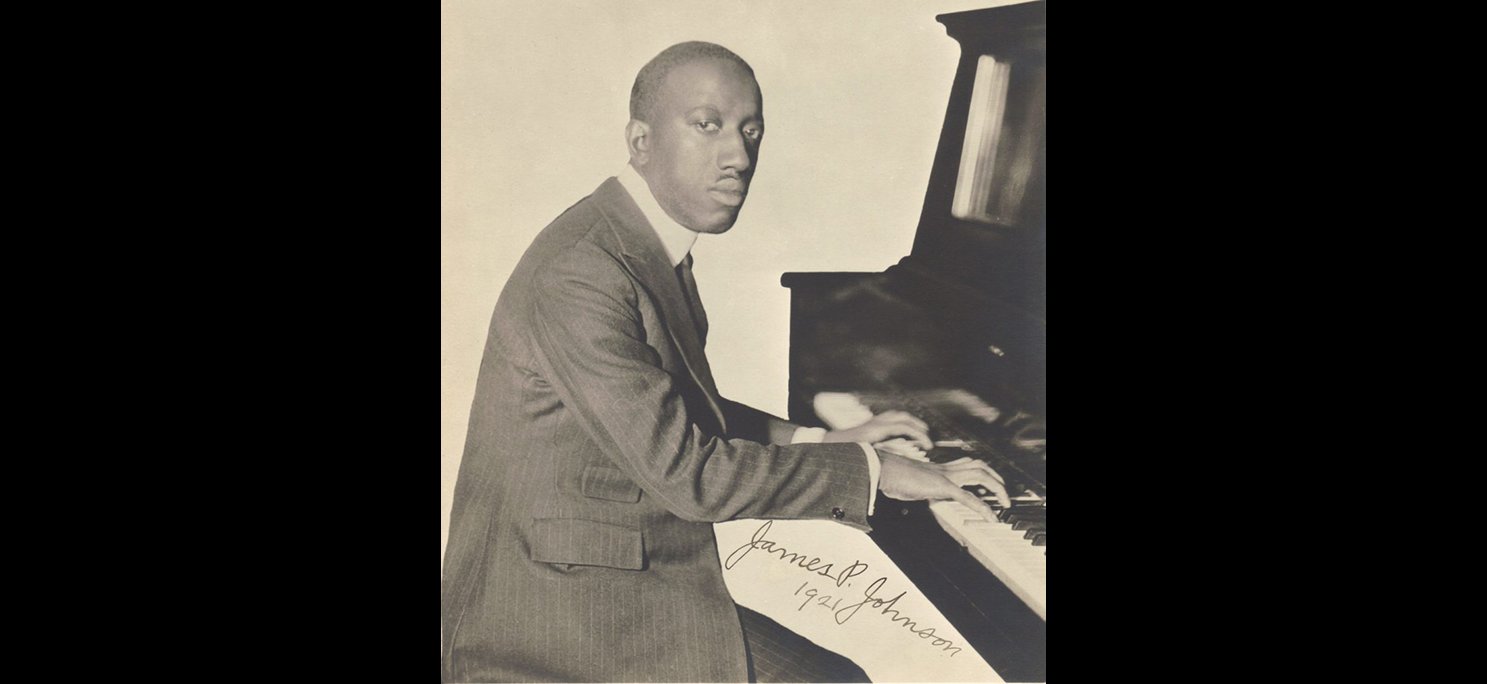

Monk was born in 1917, about a generation younger than the most influential of San Juan Hill's early composers—James P. Johnson, born 1894— so Monk did not witness the neighborhood at its most populous and creative peak, around 1909. Monk’s family moved to San Juan Hill in 1922, and after honing his talent with home piano lessons and playing at a local community center, Monk began to encounter opportunities to play and learn from James P. Johnson and many other musicians in the neighborhood.

In James P. Johnson's San Juan Hill, despite the prowess he and his contemporaries possessed, the color line dominated the creative and social worlds where these, mostly men, sought to intervene. Johnson, Eubie Blake, Willie "the Lion" Smith, Fats Waller, Luckey Roberts, Ram Ramirez, and others would not experience some of the artistic freedom Monk achieved—but perhaps Monk's cross to bear was that he would see his beloved San Juan Hill "go to pot" as former resident Roseanna Weston described it. In her view, which Robin D.G. Kelley’s biography supports, drug use led to the decline of the neighborhood, making it a target for urban renewal.

Unlike most, Monk stayed in San Juan Hill as widespread demolition dismantled the neighborhood. This began in the 1930s under Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Monk’s career progressed slowly for decades until his music became the subject of major widespread interest in the late 1950s into the 1960s.

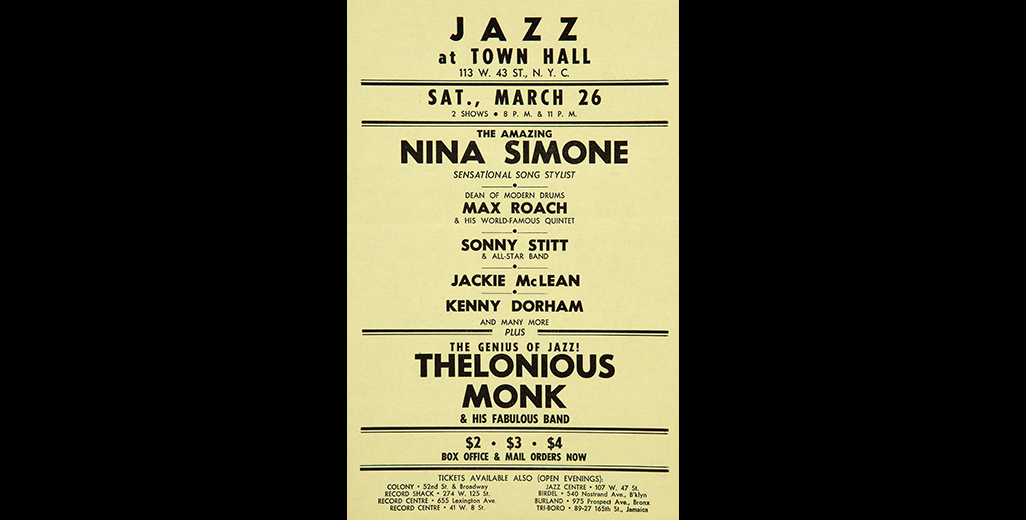

Traveling just a few blocks from his Phipps Houses apartment (among the only early buildings that still stand to this day in Lincoln Square) Monk carried the neighborhood legacy of Johnson and others to Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center's first performance space, just one year after its opening. In December 1963, he became the first jazz musician to record an album live in Philharmonic Hall, Big Band and Quartet in Concert.

Nina Simone’s Turn

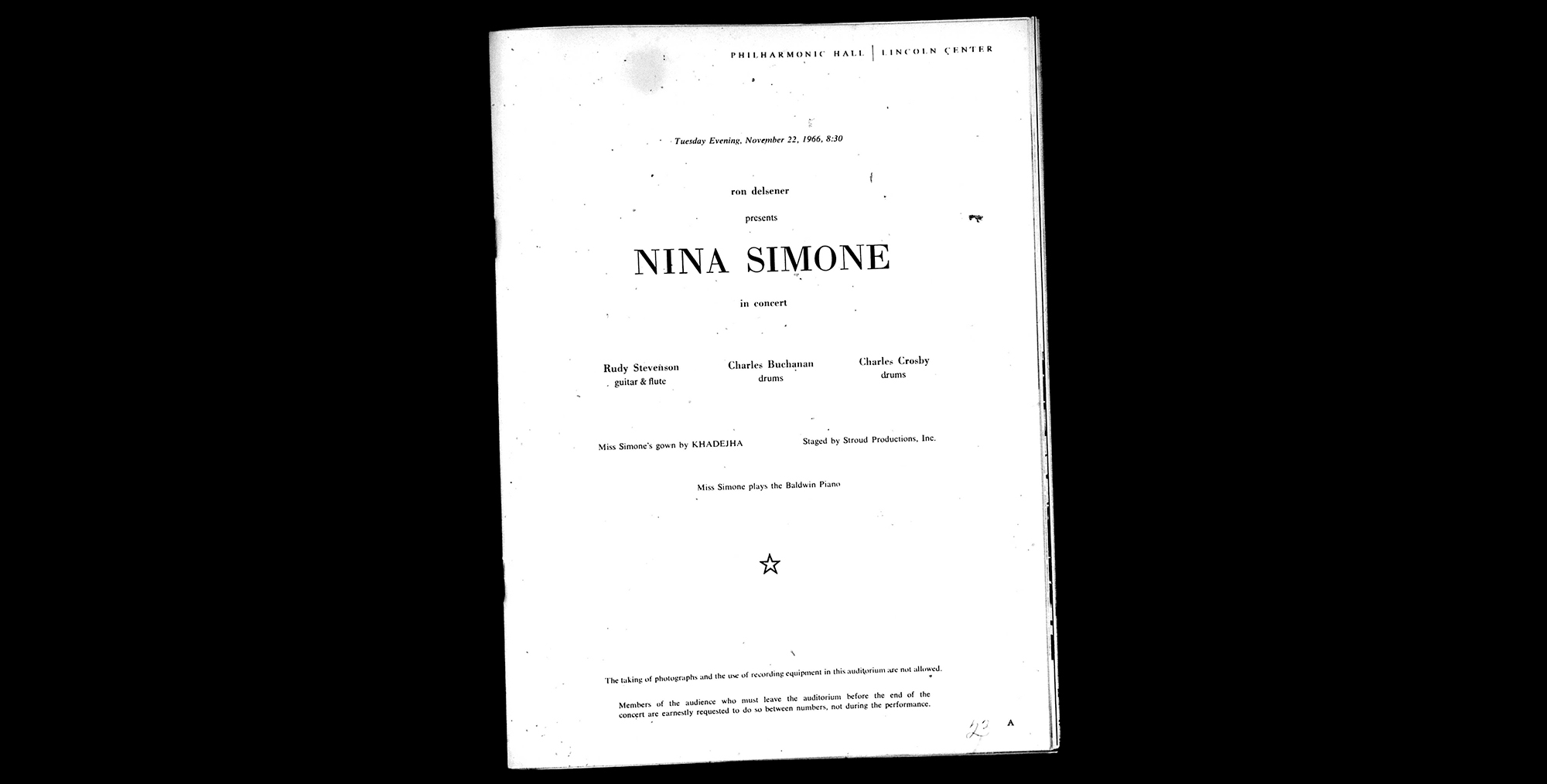

Nina Simone's Lincoln Square was a place where a Black woman could take to the stage and deliver her own words. Simone emerged there in the mid 1960s to early 1970s as she was remaking her life.

At this time, the area was increasingly known as the Upper West Side, though it was once considered midtown Manhattan. Many Black artists were attracted to this area because it was one of New York's "interracial Left" spheres, in the words of historian Ruth Feldstein. Feldstein describes such places as highly desirable areas to reside for “entertainer-activists” who made art that spanned genres and appealed to diverse audiences. Decades earlier, San Juan Hill attracted interracial audiences and artists too, but renewed hostility toward interracial relationships also made many of these spaces volatile and unsafe.

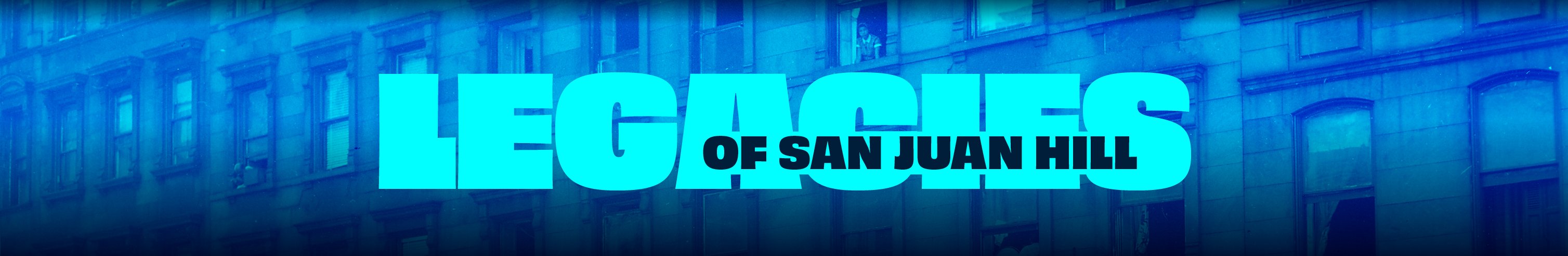

Nina Simone lived safely in her apartment in the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) building and showed up at Lincoln Center to watch performances. The audiences she reached in the late 1960s and early 1970s were welcoming and adoring fans. They were not stigmatized as thrill seekers, or "slummers" as earlier white audiences in San Juan Hill were labeled, and audiences of color developed here too. Nina Simone recorded two albums at Lincoln Center—Black Gold (1970) and It Is Finished (1974)—and appeared in Lincoln Center house program advertisements.

Without Nina Simone's presence at Lincoln Center in 1966, 1969, 1970, and 1971 would the institution have mounted the 1972 Soul at the Center, a festival headlined by Simone and dedicated entirely to Black music and art? This was precisely the moment that Simone took up full-time residence in the neighborhood of Lincoln Square. Nina Simone did not pass through the Center without influence.

Monk Meets Simone

While they are very different artists, Thelonious Monk and Nina Simone arrived at the pinnacle of their careers around the same point in the 1960s. By this time Monk's home was in this new neighborhood too, in a more modern unit in Lincoln Towers. But he also never let the spirit of his childhood home in the Phipps Houses go. He kept that apartment too.

Monk and Simone's historically significant appearances at Lincoln Center in its early years elevated their careers and brought modern jazz and soul music to the Center.

The way people received these artists was almost on a spiritual level. Monk was known to many as the "High Priest of Bebop," and Simone was often called "the High Priestess of Soul." While often classified as jazz pianists, both could interpret Bach, Chopin, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff expertly enough to be notable for this alone. Their forays into the genres of bebop and soul as opposed to other forms of concert piano has a good deal to do with what the country was prepared to hear from Black musicians during their careers, even as the social climate in the United States evolved during the Civil Rights movement and beyond.

People said that when Simone played piano she evoked Monk, as well as her unique sound. Her longtime accompanist Al Schackman told biographer Alan Light, “The closest person that had a sound that was not Nina but similar was Thelonious Monk. The way he used chord clusters and it sounded like dissonance or like somebody slamming an elbow, but it was a real musical experience, like Jackson Pollock throwing a can of paint on a canvas. I put her in a place with Ravi Shankar or Glenn Gould.”

When Monk played his unique sound, he evoked the first generation of stride pianists, but also sharply departed from them.

In the decades that have gone by, some of their most-loved songs—such as Monk's "'Round Midnight" and Simone's "Please Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood"—have been performed countless times across the stages of Lincoln Center.

The legacy of the pianists before them has also been present on Lincoln Center's stages—but so far that history is less well-known. It is not surprising that most of the musicians of San Juan Hill who set the stage did not receive their due in their lifetime.

Lincoln Center’s archives show that there are indeed additional traces of San Juan Hill at Lincoln Center worthy of exploration. There are also areas to add to the historical record of instances where San Juan Hill has been omitted or overlooked.

Echoes of San Juan Hill

In an interview in the book In the Spirit of Swing: The First 25 Years of Jazz at Lincoln Center, a retrospective published in 2012, a former staffer recounts: "I can never forget… Benny Carter reminiscing and walking around Lincoln Center with me. He had grown up just behind the campus and said, 'This is where my house used to stand.'"

Benny Carter (b. 1907 – d. 2003) premiered his composition "Echoes of San Hill" at Lincoln Center with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra in 1996. The suite was later recorded by Jazz at Lincoln Center and released in 2009 as Movin' Uptown–From Echoes of San Juan Hill.

Carter also performed in the Classical Jazz series that took place in Alice Tully Hall on multiple occasions, performing there for the first time in 1989, and then again in 1990. The Lincoln Center archives contain some correspondence with Carter, and in 1989 he agreed for his likeness to be illustrated by Harry Pincus for a commemorative poster for Classical Jazz. (Dizzy Gillespie also agreed for his likeness to be used, and Thelonious Monk is depicted too.)

Eubie Blake (b. 1887 – d. 1983) played piano in Philharmonic Hall on December 27, 1972. This engagement was part of a holiday event called "A Ragtime Xmas" organized by George F. Schutz. Blake, who performed in San Juan Hill but did not make his home there, composed the music alongside Noble Sissle for the 1921 musical Shuffle Along, which debuted in the neighborhood at the 63rd Street Music Hall on May 23, 1921. A musical descendent of Blake, the great pianist Emme Kemp presented a program called "Eubie Blake is Great" in the 1984 Out-of-Doors Festival at Lincoln Center.

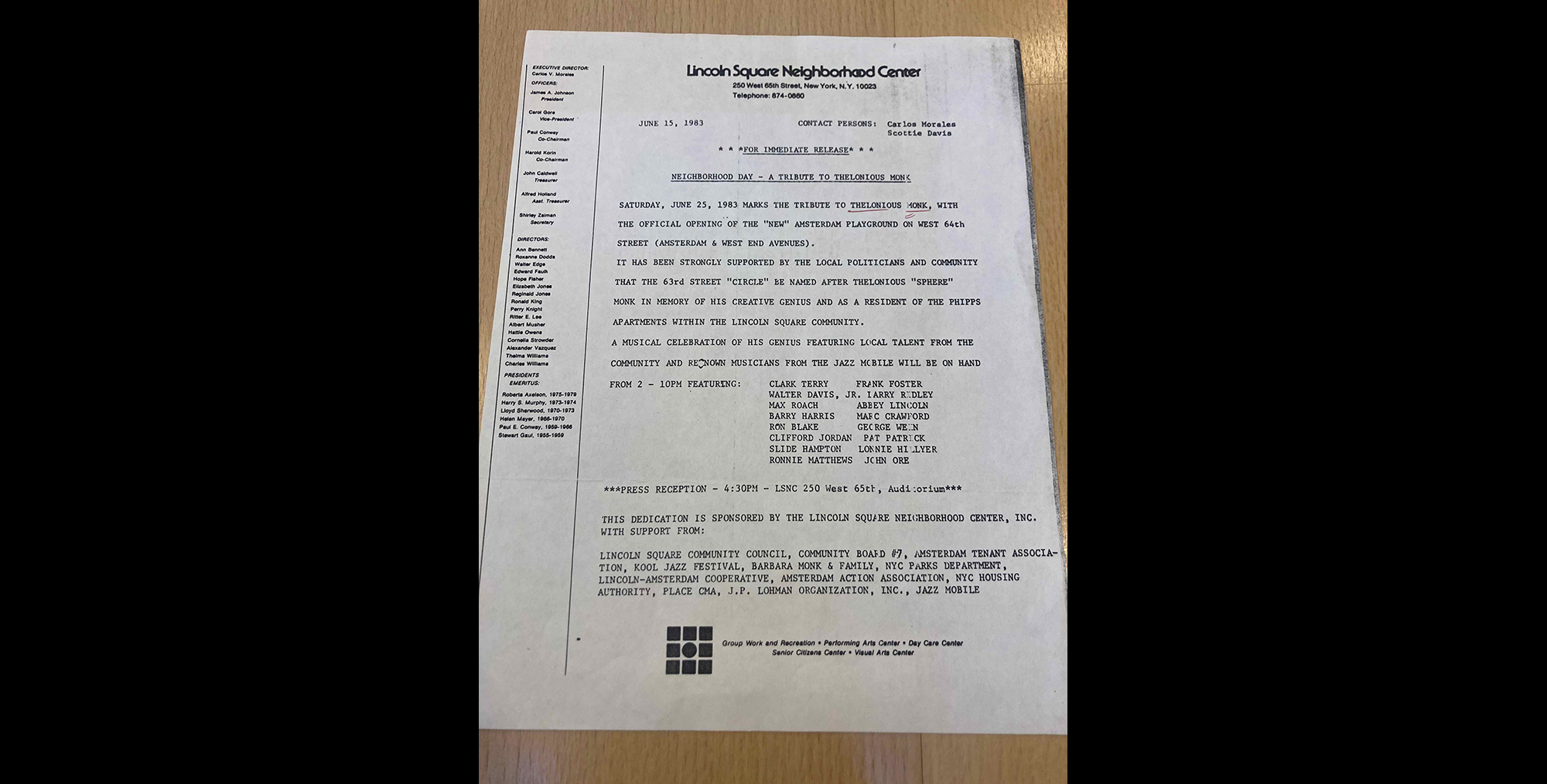

Monk's last two engagements in Philharmonic Hall were part of the 1972 and 1975 Newport Jazz Festival. Later, Monk's music was the focus of many events in the Classical Jazz programs of the 1980s. We found programs that honored his legacy in 1987, 1992, and 1993, and he continues to be honored to this day by Jazz at Lincoln Center with more than half of his original compositions part of the repertoire of the orchestra in 2023.

Over the years, many events also honored several influential ragtime, stride, and swing pianists and musicians of San Juan Hill who did not live long enough to appear on stage at Lincoln Center.

Efforts to acknowledge and incorporate the music from San Juan Hill appear in programs like "In Stride with Fats, The Lion, and James P. Johnson," an evening of rare film footage and live stride piano performance by "third-generation" stride pianist Mike Lipskin in October 1995. The American Songbook "At Harlem's Height" concert in February 2005 also included compositions by Fats Waller (b. 1904 – d. 1943), Smith (b. 1893 – d. 1973), and Johnson (b. 1894 – d. 1955).

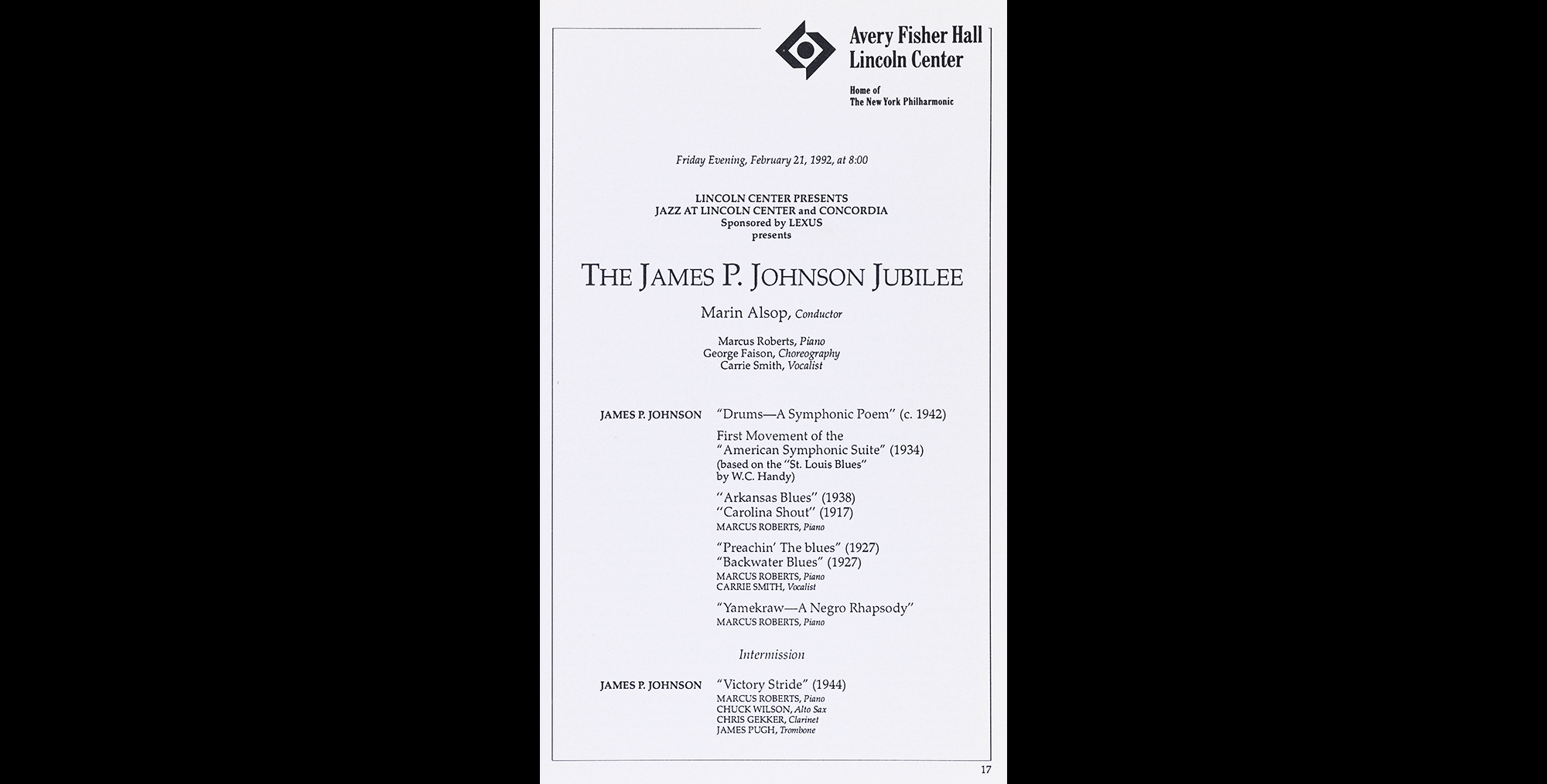

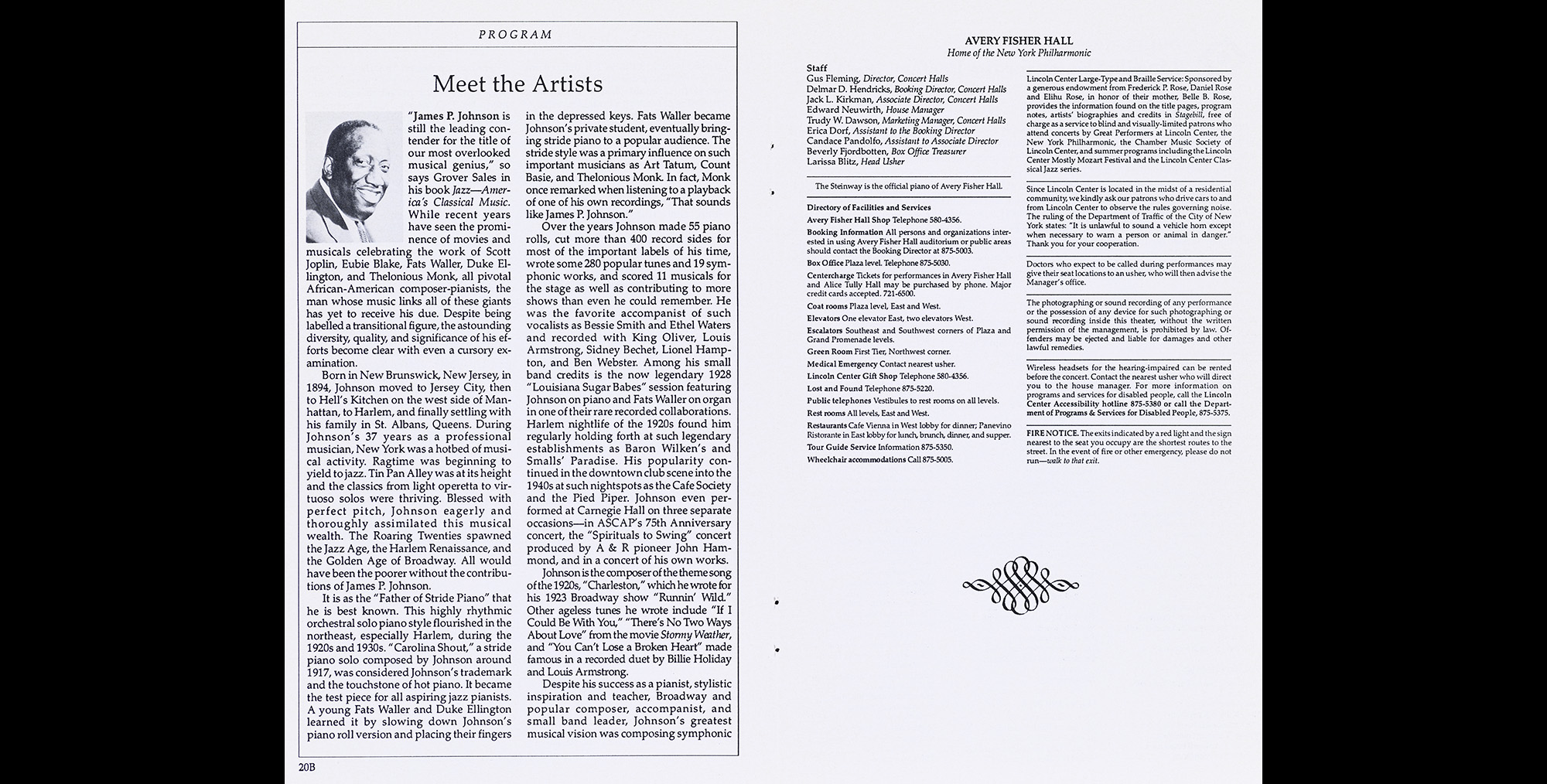

A February 1992 event, "The James P. Johnson Jubilee" took place over two days at Avery Fisher Hall and the Snug Harbor Cultural Center in Staten Island. The New York Times reported that this was the first time the still-new program in jazz had been performed in Lincoln Center's largest space—formerly known as Philharmonic Hall, and at the time called Avery Fisher Hall.

Along with pianists Marcus Roberts and Leslie Stifelman, conductor Marin Alsop set out to fully honor Johnson's life: "According to Ms. Alsop, three pieces on the program—'Drums -- A Symphonic Poem' (c. 1942), 'Harlem Symphony' (1932) and the first movement (all that has been found) of the 'American Symphonic Suite' (1934)—had not been performed since the 1940s, and one, a 1944 arrangement of 'Victory Stride' for piano and orchestra, had never been played in public."

The elusive nature of neighborhood identity and boundaries can be discerned in the house programs of some of these events. At the time, most jazz house program notes were written by Stanley Crouch. Crouch described Johnson as living in Hell's Kitchen, Smith is described as of Harlem. There is no mention of Thelonious Monk being of San Juan Hill in house programs or in other early descriptions of jazz at Lincoln Center. And these are just the widely known names.

Each jazz ensemble or arrangement that has made it to a Lincoln Center stage consists of accompanists and journeymen. There are certainly unrecognized artists with ties and stories about San Juan Hill among them.

Close to Home

Part of the reason musical histories of San Juan Hill are hard to establish is because of the informal and intimate settings in which much composition took place.

Monk was a “house pianist” first in San Juan Hill, because his piano was in his kitchen and his guests listened to his new work from there. After leaving a stint playing at Minton's Playhouse in Harlem, Monk began inviting musicians who seemed to have something to say about the direction of jazz to his home to play together. So much experimentation in modern jazz took place right in the Phipps Houses of San Juan Hill. The saxophonist Sonny Rollins once reflected: "Every day after school I would go to Thelonious Monk's house to practice with his band."

This tradition of inviting promising musicians to play together in one’s home was already well-established a generation earlier with James P. Johnson in San Juan Hill. Johnson was well-known for participating in "cutting contests," that is, hours-long, call-and-response improvisations on piano between pianists jamming with and against each other that often took place in someone’s home.

There were venues to perform uptown in Harlem, but many musicians had a desire to play closer to home. "Colored folk didn't frequent the downtown hotels," Ram Ramirez told Marian McPartland in an interview. Ramirez was a pianist of Puerto Rican heritage who grew up with Benny Carter in San Juan Hill, a bit before Monk’s active career began.

James P. Johnson had been something of an official house pianist at Drake's Dancing Class, or Jungles Casino in San Juan Hill. This establishment was just one of the rooms for dance and performance carved out of tenement building cellars in San Juan Hill. Most of these spaces were not glamorous and fashioned from very little in tenements that were designed explicitly as Black housing or became de facto majority Black housing.

"One night a week, I played piano," recounts James P. Johnson in an interview. "It was officially a dancing school since it was very hard for [us] to get a dance-hall license. But you could get a license to open a dancing school very cheap." He adds, "The Jungles Casino was just a cellar, too, without the fixings… There were dancing classes all right, but there were no teachers."

People danced the Charleston at these clubs because Black Americans from the Carolinas and other states in the South were coming to New York and mixing their cultural heritage with that of New York. San Juan Hill was a neighborhood where a “house pianist” could have a hand in Broadway, and what was once a regional flavor could go on to resonate widely in the world.

These legacies aren’t reflected on plaques or building names or archival records, but they are very much tied to what is now Lincoln Square. How might this history be revealed today?

Palace of Jazz

During the construction of Lincoln Center in 1961, an activist group called the Emergency Committee for Unity on Social and Economic Problems called upon Lincoln Center leaders to establish a building to serve as a "Palace of Jazz" as part of the new cultural center, alongside its planned "Palaces of Opera and Ballet." They reasoned that jazz should be part of the fabric of the institution from the beginning to highlight Black contributions to American music.

Jazz became part of regular programming at Lincoln Center in the late 1980s, and Jazz at Lincoln Center was established as a constituent in 1996. But perhaps there is more to be done to memorialize the jazz legacy of the West Side of Manhattan. A legacy that includes Thelonious Monk, Nina Simone, Benny Carter, Ram Ramirez, James P. Johnson, Eubie Blake, Willie “the Lion” Smith, Fats Waller, Luckey Roberts, Emme Kemp, Billie Holiday, and so many more.

This essay serves as an introduction to what we know San Juan Hill once was. Future efforts might take up what San Juan Hill might have been or may become once again.

This essay is adapted from the Lincoln Center Archives Exhibition Thelonious Monk’s San Juan Hill, Nina Simone’s Lincoln Square now on view in David Geffen Hall.

Sources:

Booker, Eric, et al. Just above Midtown: Changing Spaces. The Museum of Modern Art, 2022.

Cohodas, Nadine. Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

De Wilde, Laurent. Monk. Marlowe, 1997.

Feldstein, Ruth. How It Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Sacks, Marcy S. Before Harlem: The Black Experience in New York City before World War I. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. First edition, W.W. Norton & Company, 2019.

Monk, Thelonious, and Jacques Ponzio. Thelonious Monk: Abécédaire, AB C-Book. Lenka lente, 2017.

Kelley, Robin D. G. Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original. 1st Free Press trade paperback ed, Free Press, 2010.

Light, Alan. What Happened, Miss Simone? A Biography. Crown Archetype, 2016.