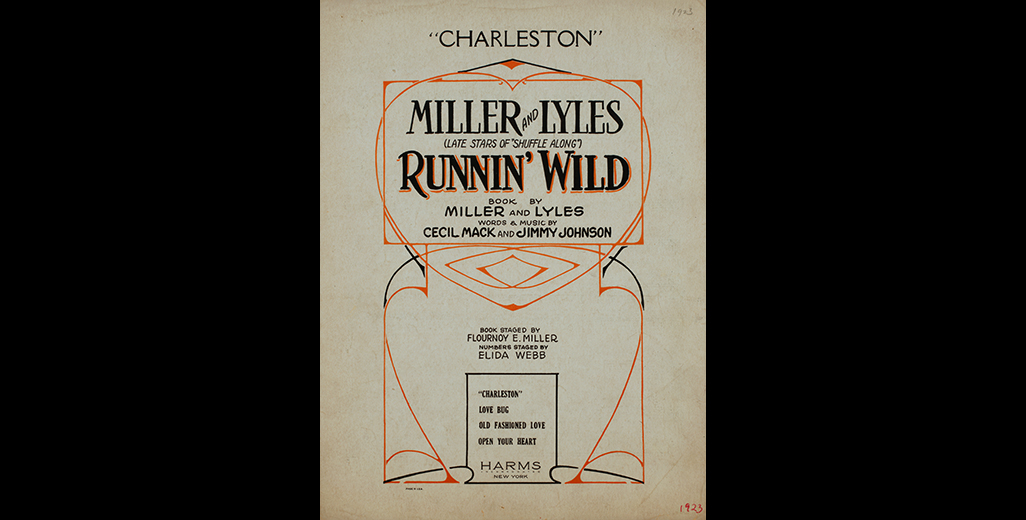

Chorus of Runnin’ Wild, 1923

Photo: New York Public Library

From the Vaudeville Wars to Runnin’ Wild: Lincoln Square’s Early Theaters

August 20, 2025

by Catherine M. Young

In the first decade of the twentieth century, theater entrepreneurs cast their sights on Lincoln Square, the area on the west side of Manhattan that “stretched from 57th Street to 72nd Street or so.”1 New York businessmen angled to expand their theatrical enterprises amidst ruthless theater wars. This was true for the so-called legitimate theater (which included plays, musical comedies, and light opera) and the “polite” variety theater known as vaudeville in which several unrelated short acts were presented on a single bill of comedy, singing, dancing, and circus-style turns. This capitalist conflict fueled a striking array of theatrical undertakings. A closer look at the venues and productions reveals dynamics riven with class and racial tension, yet full of entrepreneurial striving amidst rapid societal transformation.

Vaudeville businessmen with formidable mustaches and financial acumen, Benjamin Franklin (B.F.) Keith, Percy Williams, and William Morris battled to control more theaters and book the best performers.2 The frenzy for vaudeville and legitimate theater supremacy instigated a theater building boom that kept shimmying its way north from Union Square.3 For, although it was not until 1904 that Manhattan’s old horse carriage district known as Longacre Square was renamed Times Square, the 1890s had already seen significant investments in new theaters between 40th and 45th Streets.4 Some developers speculated that Lincoln Square would be next, and by 1910, a new commercial theater scene had surfaced there.

The Circle and the Lincoln Square Theaters

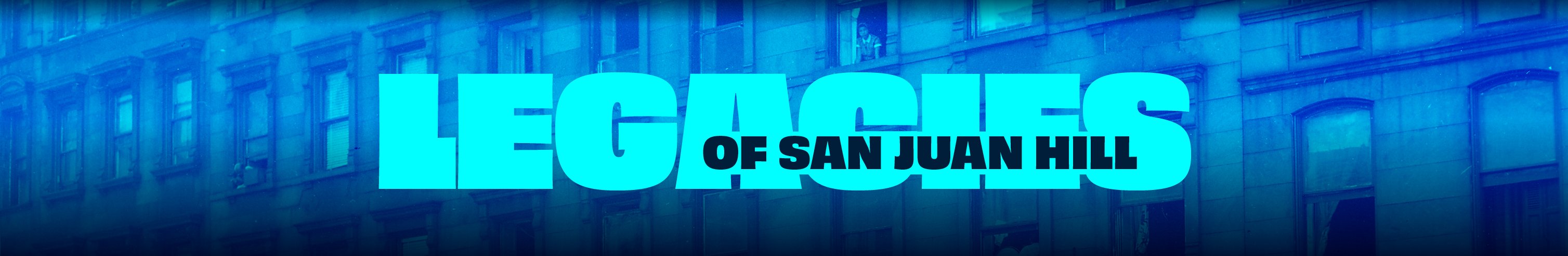

Theater owners Charles Evans and W.D. Mann hoped to open the Circle Music Hall at 60th Street and Broadway with a design by Charles Cavanaugh in 1900. However, their variety programming faced religious pushback, and the venue could not turn a profit when it opened with orchestra offerings in 1901.5 Despite the initial variety theater controversy, the affable and savvy vaudeville theater owner Percy Williams leased the Circle in 1902. A February 1903 playbill (Figure 1) promises “REFINED VAUDEVILLE” and promotes a daily “Ladies’ Matinee” to signal that the Circle was safe and respectable—unlike other variety entertainments such as burlesque. For the headliner, Williams booked the Irish American Russell Brothers, a duo performing ethnic stereotype in drag as “The Irish Servant Girls.”6

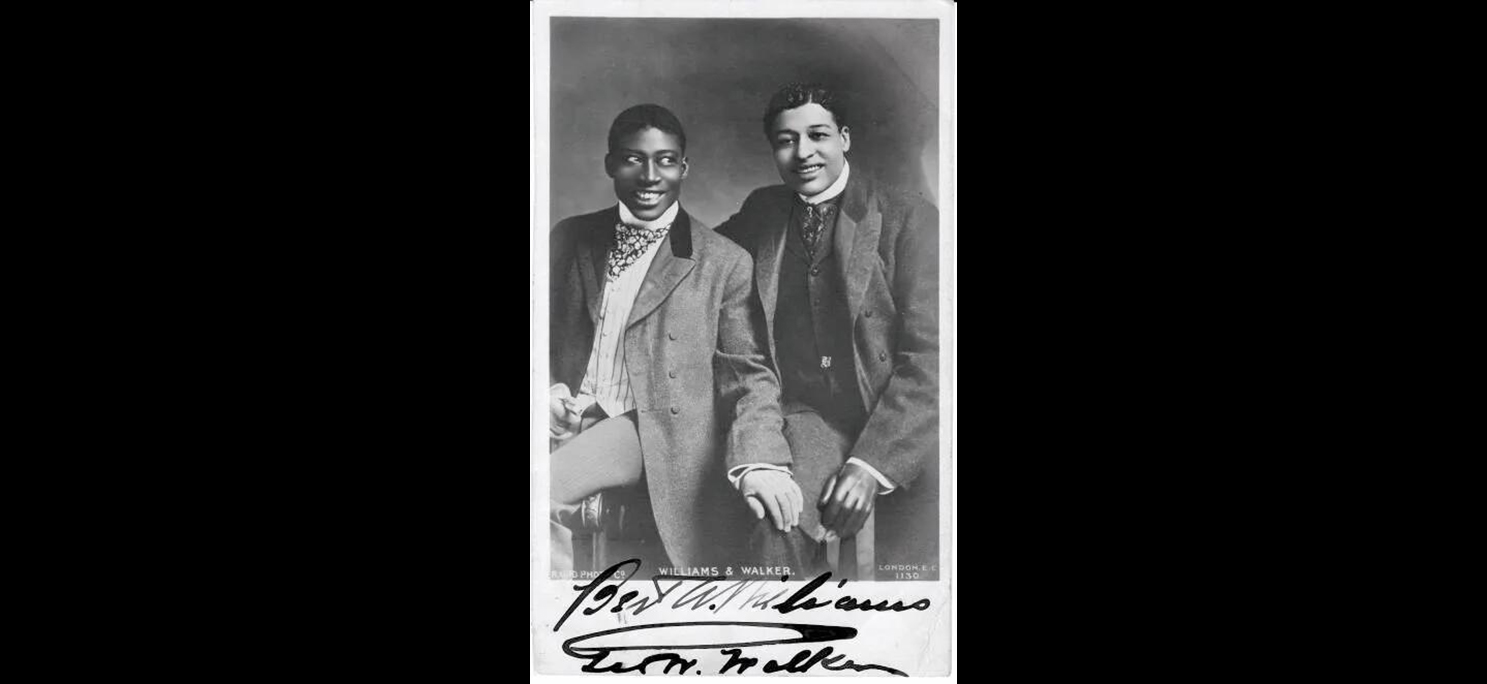

Ethnic and racial stereotypes were a major part of vaudeville. White and Black performers sometimes sang ragtime hits and gave minstrelsy-style comic turns in blackface. At the same time, theater managers illegally segregated Black audience members by requiring them to sit in the upper gallery. Box office attendants refused to sell orchestra seats to Black customers, and ushers ensured the orchestra stayed a whites-only space. As enraging as these Jim Crow constraints were, many Black entertainers still booked white vaudeville houses, finding ways to contend with a nearly impossible situation. For example, the week after the Russell Brothers’ appearance, the Circle featured the internationally famous African American married couple Johnson and Dean, billed as “The Fashion Plates of Vaudeville.”7

As performers successfully navigating commercial entertainment during the Jim Crow Era, Charles E. Johnson and Dora Dean wore evening attire, danced the cake walk, and sang songs by major Black composers. They also sang popular songs with lyrics (and sheet music covers) filled with racial stereotypes. However, Johnson and Dean’s sophisticated self-presentation somewhat subverted minstrelsy conventions.8 Thus, just as Black audience members had restricted access to white-owned and operated theaters, Black artists worked within larger racist contexts to sustain their careers. Meanwhile, to make programming decisions, vaudeville impresarios had to anticipate audience taste while keeping an eye on the competition.

The Shubert Brothers were in their own all-consuming battle with the Theatre Syndicate to control legitimate theater, leading the Shuberts to expand to Lincoln Square with a popular price venue.9 Lee and Jacob (J.J.) Shubert opened the Lincoln Square Theatre at Broadway and 66th Street in October 1906 with a melodrama from Chicago: The Love Route by Edward Peple. The building’s plain dark brick façade and unassuming entrance belie the interior’s decorative details, including drop curtains “depicting a scene in the Orient” and a ceiling frieze.10 The top ticket cost $1 instead of Times Square’s $2 orchestra seats. However, even at this more affordable price, the venue would not remain a legitimate theater house.

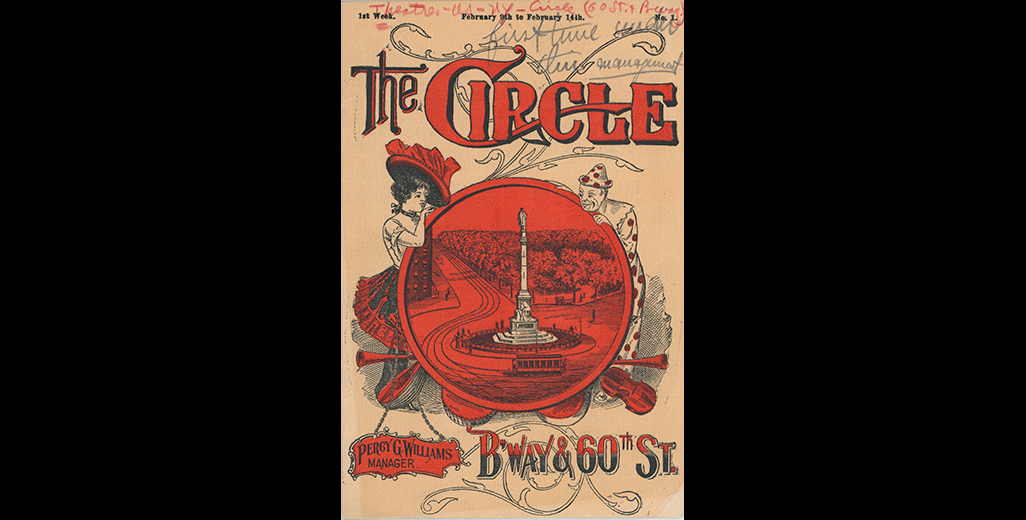

A February 1, 1909 playbill (Figure 2) reveals playwright and director Charles E. Blaney operated the venue as part of independent owner William Morris’s vaudeville chain.11 Morris had been blacklisted by B.F. Keith, preventing Morris from booking the top-tier acts Keith controlled. This ultimately forced Morris to sell his chain to the future movie executive Marcus Loew.12 After 1909, Loew’s Lincoln Square Theatre showed films, and tickets ranged from 10-25 cents.13 The building remained until it was demolished as part of Lincoln Center’s construction. Today, it is the location of the Juilliard School.

The Colonial Music Hall

Just a few blocks away at 62nd Street and Broadway, theater builder Meyer R. Bimberg hired architect George Keister to design the Colonial Music Hall with a Federalist façade of unadorned windows and Ionic columns facing Broadway. Inside was “decorated in bright red, gray, and watered silks” with seating for 1,265.14 Business partners Fred Thompson and Elmer Dundy leased the Colonial to expand their entertainment enterprises. They had built Coney Island’s Luna Park in 1903 and were also constructing a massive circus and variety venue called the New York Hippodrome at Sixth Avenue between 43rd and 44th Street.15

A rapturous description of the Colonial promoted it as “the latest playhouse on the famous theatrical thoroughfare” of Broadway.16 Essentially a press release masquerading as news, it’s clear that Thompson and Dundy wanted to connect the rather distant 62nd Street location with Times Square’s hub of theatrical activity. Coverage boasted that the Colonial was just like London’s West End Empire and Alhambra theaters, with “a cheerful smoking gallery” and “a cosey [sic] tea and coffee room at the rear of the mezzanine balcony” decorated in crimson and gold.17 Emphasizing the venue’s extravagance aimed to mitigate the public’s suspicion of variety theater.

The Colonial opened on February 8, 1905, with a line-up including a three-scene British ballet pantomime titled The Duel in the Snow.18 Next came the one-act musical comedy farce The Athletic Girl by George V. Hobart and composer Jean Schwartz. It was set in “the ‘gym’ of a girls’ university in The Bronx” where “pretty maidens have developed muscles and strength which enable them to eject all objectionable men from the institution.”19 The comedy played on assumptions about femininity amidst the era’s intense debates about women’s proper role in society. The opening bill then pivoted to variety offerings, including balancing, tumbling, and “Carl and his wrestling bear.”20 It was risky to mix circus-style acts and indoor theater productions because large animals could be dangerous and trainers could be negligent.21 Indeed, Carl’s performing bear “severely scratched” the lead of The Athletic Girl, Libby Arnold Blondell, and the accident delayed the Colonial’s opening.22

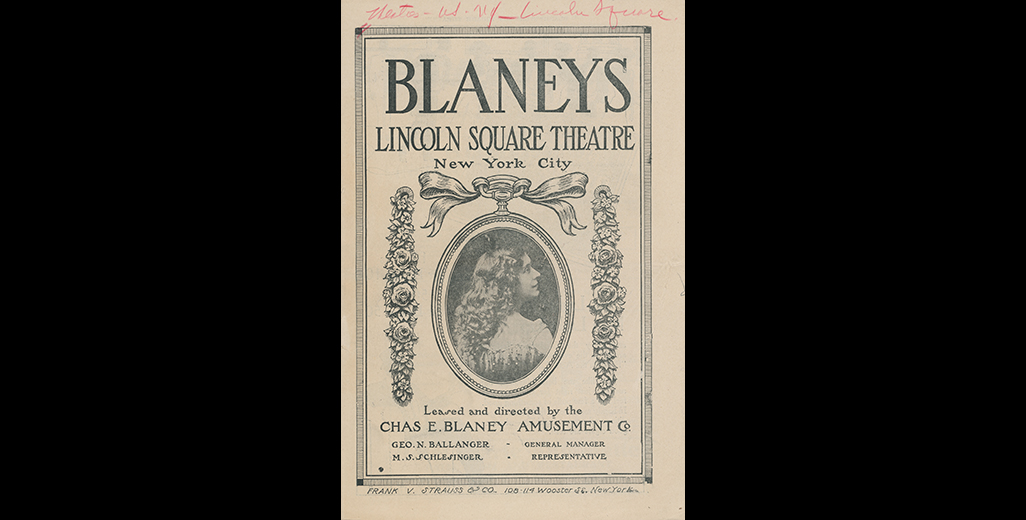

After just a few months, Percy Williams took over the Colonial (see playbill cover, Figure 3). His selection of acts indicates Williams’ commitment to a balanced bill and the Colonial’s polite vaudeville status. The week’s line-up for May 1, 1905, included the “European Novelty Act” the Lutz Brothers, husband-and-wife farce team (Raymond) Finlay and (Lottie) Burke, Canadian melodrama actress Clara Morris, a magician, the legitimate stage actor Edwin Stevens, and dancers John Ford and Mayme Gehrue.23

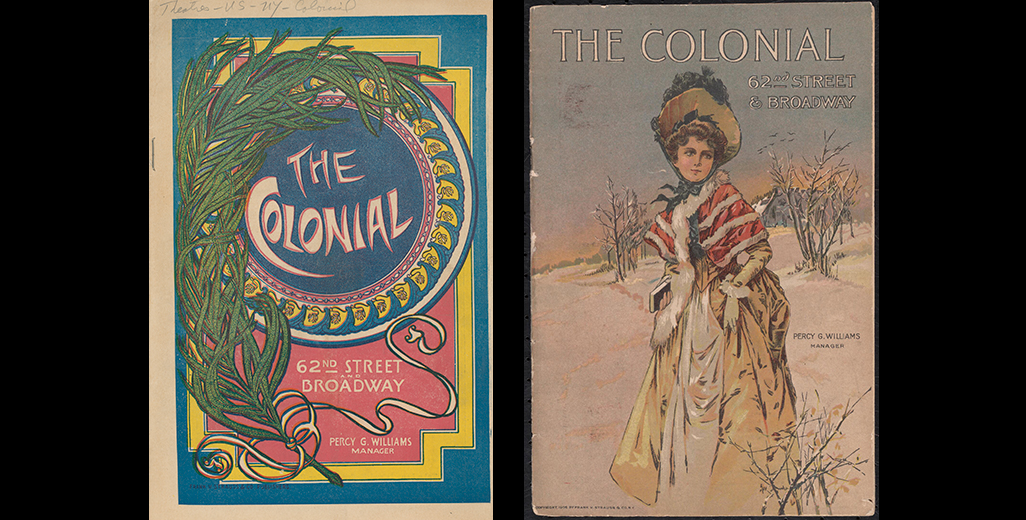

Williams ran the Colonial for several years while New York City was rapidly changing as cars and skyscrapers became common sights. A 1911 program (Figure 4) promotes “MODERN VAUDEVILLE”—In just six years, concerns about vaudeville’s respectability had become less important than seeming current. Part of vaudeville’s modernization included consolidation. In 1912, the monopolistic Keith-Albee Circuit bought all of Williams’ theaters. Keith had won the war. Renamed Keith’s Colonial Theatre, it remained a vaudeville house until 1923, when vaudeville was on the decline and the Jazz Age pulsed through Manhattan.

The Jazz Age in Lincoln Square

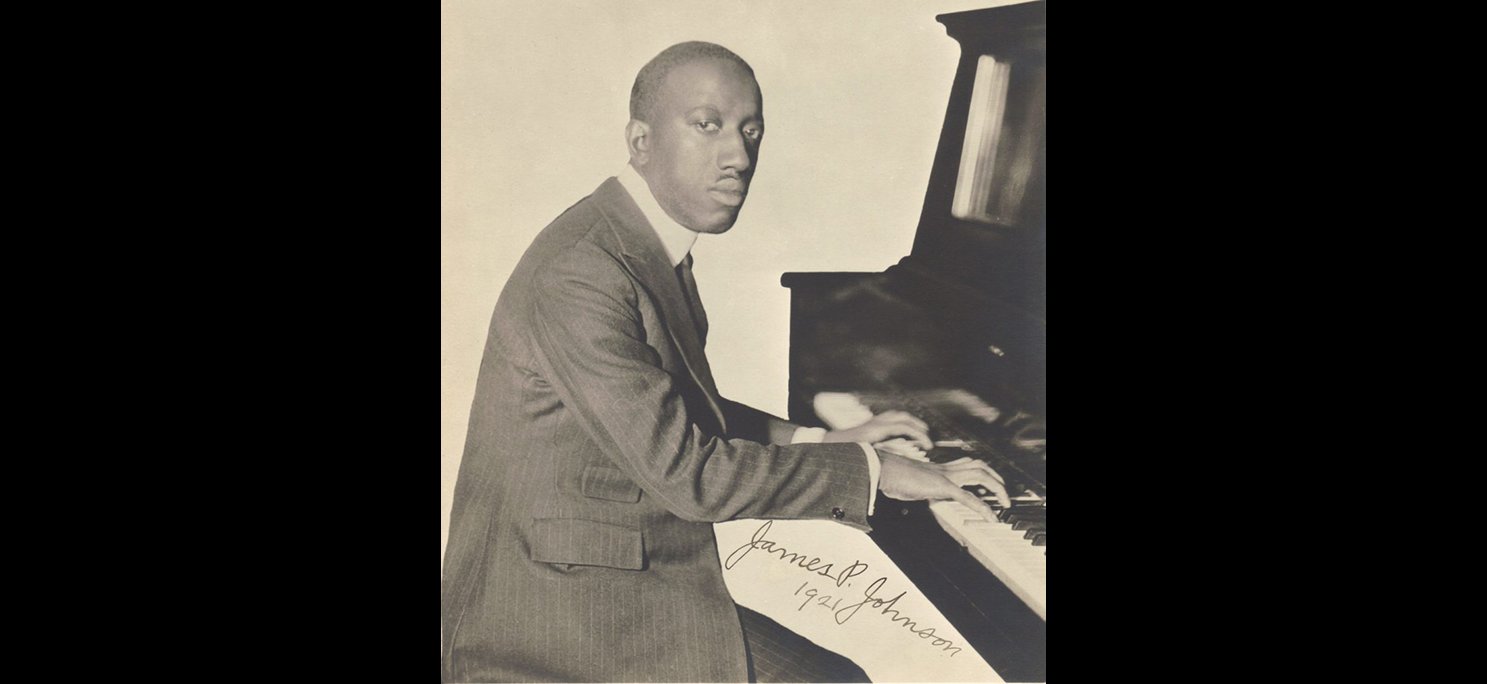

The Colonial became an important site of Black popular performance history. On October 29, 1923, the New Colonial Theatre switched to musical comedy when Runnin’ Wild made its New York City premiere.24 James P. Johnson, who had worked on other shows and played piano in San Juan Hill clubs, composed syncopated tunes for Runnin’ Wild, including the spirited, cut time “Charleston” (Figure 5).25 Perhaps of greatest cultural consequence, Elida Webb choreographed the show, which featured the iconic Jazz Age dance the Charleston, a jaunty back-to-front kick step with accompanying arm movements. Although the dance had emerged out of South Carolina with roots in Gullah Geechee ring shouts and dances, and had circulated in Black street and social dance for years, Webb “staged what would become known as the signature version of the Charleston.”26

Before it popularized the Charleston, Runnin’ Wild was a comedy enterprise authored by successful Black comedians F.E. (Flournoy) Miller and Aubrey Lyles, who had performed in vaudeville routines for years. Miller and Lyles hoped Runnin’ Wild would be at least as successful as Shuffle Along, the 1921 hit musical that ran at the close-by 63rd Street Music Hall and transformed Broadway. Miller and Lyles had written Shuffle Along’s book and starred in it. The popular team of lyricist Noble Sissle and composer Eubie Blake crafted the catchy syncopated tunes, and a chorus of talented dancers “articulated the new urban moment.”27 Created by an all-Black artistic team but funded by white producers, Miller, Lyles, Sissle, and Blake insisted that Black audience members be able to purchase orchestra seats, thus partially integrating Broadway. Shuffle Along demonstrated “that Black musicals were an artistically and commercially viable enterprise.”28 Indeed, “in just three years, New Yorkers saw nine musicals written by and starring black performers.”29

Ironically, Shuffle Along’s tremendous success wound up preventing another innovative collaboration between Miller and Lyles and Sissle and Blake. The comedians fought with the musicians for royalties stemming from sheet music sales and live concerts, ending their professional relationship.30 Miller and Lyles teamed up with Scandals producer George White and cast Runnin’ Wild with several Shuffle Along veterans, particularly the stand-out performers Adelaide Hall and Elida Webb. Lyricist Cecil Mack replaced Sissle, and the groundbreaking musician and composer Will Marion Cook conducted Johnson’s compositions.

Runnin’ Wild’s “thin plot” told the tale of “Steve Jenkins (Miller) and Sam Peck (Lyles), who flee Jimtown when insurance investigators discover a clever plan to bilk their company of thousands of dollars.”31 As the character Ruth Little, Elisabeth Welch (sometimes spelled Elizabeth Welsh) sang Johnson and Mack’s “Charleston” and danced with the Runnin’ Wild chorus (Figure 6). In Black Manhattan, James Weldon Johnson explains that the chorus accompanied the band “by beating out the time with hand-clapping and foot-patting. The effect was electrical. Such a demonstration of beating out complex rhythms had never before been seen on a stage in New York.”32

The show began its out-of-town try-out at the Howard Theatre in D.C. and then spent eight weeks in Boston gaining buzz and financial stability before arriving at Lincoln Square’s New Colonial Theatre. Runnin’ Wild was reviewed well, with some critics saying Miller and Lyles’ comedy was even better than in Shuffle Along.33 It played 228 performances at the Colonial—impressive, but nothing near Shuffle Along’s 484 at the 63rd Street Music Hall.

In fact, the next show at the New Colonial was Sissle and Blake’s post-Shuffle Along effort, The Chocolate Dandies, in which Josephine Baker was billed as “That Comedy Chorus Girl. A Deserted Female.”34 Despite its promising provenance and production values—including live horses depicting a race à la Ben Hur! —The Chocolate Dandies’ weak book did not impress audiences, and it closed after 96 performances.

A few more musical comedies appeared at the Colonial until 1925 when the actor Walter Hampden leased the theater to stage plays.35 As a clear sign of the times, in 1931, the venue became a movie house named RKO Colonial Theatre. The “K” in RKO stood for Keith. The once-mighty Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit had been absorbed by a modern media conglomerate.36 Eventually, the Colonial became a television studio, and then returned to being a live performance venue that couldn’t recapture its former appeal. It was demolished in 1977, long after the opening of Lincoln Center.

Lincoln Square’s commercial theaters tell a larger story about popular entertainment’s shift from vaudeville to Jazz Age musicals, as well as just how important the neighborhood was to Black cultural production. The vibrant commercial theater scene developed piecemeal, driven by entrepreneurial competition at a time when many New Yorkers attended live performances a few times a week, eagerly seeking novelty, humor, and snappy songs. There are few remnants of this lively era visible in Lincoln Square today, but it’s a vital part of the neighborhood’s theatrical history and artistic legacy, worthy of further exploration.

Notes

1 Samuel Zipp, “Seeing Lincoln Square,” Legacies of San Juan Hill, https://lincolncenter.org/feature/legacies-of-san-juan-hill/seeing-lincoln-square. The author thanks Michael Love, A.J. Muhammad, and Sunny Stalter-Pace. This essay is dedicated to Michael Dinwiddie.

2 For more information on B.F. Keith and his business dealings with Percy Williams and William Morris, see Robert W. Snyder, The Voice of the City: Vaudeville and Popular Culture in New York (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1989) and Arthur Frank Wertheim, Vaudeville Wars: How the Keith-Albee and Orpheum Circuits Controlled the Big-Time and Its Performers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

3 Nicholas Van Hoogstraten, Lost Broadway Theatres, Rev. ed. (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), 13.

4 Elizabeth L. Wollman, A Critical Companion to the American Stage Musical (London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2017), 33.

5 “Circle Theatre – New York, NY | IBDB,” accessed May 29, 2025, https://www.ibdb.com/theatre/circle-theatre-1105. Van Hoogstraten, Lost Broadway Theatres, 53.

6 Circle Theatre playbill, February 9, 1903, 11, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library. To view promotional photos of the Russell Brothers as the Irish Servant Girls, see Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Russell Brothers as the Irish Serving Girls.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-3825-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Just four years later, angry pro-Irish organizations and audiences would protest the Russell Brothers’ act. See M. Alison Kibler, “The Stage Irishwoman,” Journal of American Ethnic History 24, no. 3 (2005): 5–30.

7 Circle Theatre playbill, February 9, 1903, 4, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library.

8 For a deeper consideration of these complex dynamics, see Elea Proctor, “Dora Dean and the Performance of Black Womanhood in the ‘Coon Song’ Craze,” Journal of the Society for American Music, vol.18, no.4 (2024): 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196324000403. For more on Black vaudeville, see Michelle R. Scott, T.O.B.A. Time: Black Vaudeville and the Theater Owners’ Booking Association in Jazz-Age America (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023).

9 “News of Plays and Players,” The Sun, July 27, 1906, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1906-09-23/ed-1/seq-46/. For more on the Shubert Brothers and their competition with the Theatrical Syndicate, see Foster Hirsch, The Boys from Syracuse: The Shuberts' Theatrical Empire (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000).

10 “Lincoln Square Theatre,” New York Tribune, September 23, 1906, 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1906-09-23/ed-1/seq-46/.

11 Blaneys Lincoln Square Theatre playbill, February 1, 1909, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library. Blaney had originally “installed a stock company, but they only lasted a short time.” “Lincoln Square Theatre,” Internet Broadway Database, https://www.ibdb.com/theatre/lincoln-square-theatre-1236.

12 Page 2 of the February 1, 1909, Lincoln Square Theatre playbill says “NOTE—This theatre is one of the circuit of Independent Vaudeville Houses under the direction of William Morris, Inc.”

13 Albert F. McLean, American Vaudeville as Ritual (Lexington, Ky.: University of Kentucky Press, 1965), 47. Variety described the small-time bill very favorably in June 1911, saying the line-up was “almost ‘Big Time’” and that the theater “held a capacity crowd.” See “Lincoln Square,” Variety, June 10, 1911, 25.

14 Van Hoogstraten, Lost Broadway Theatres, 90–91, “Colonial Music Hall,” New York Clipper, February 18, 1905, link

15 For more on the New York Hippodrome’s architecture and programming, see Sunny Stalter-Pace and Catherine M. Young, “Introduction to Special Issue on the New York Hippodrome,” Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 50, no. 2 (November 2023): 118–36.

16 “The Colonial Music Hall,” New York Tribune, January 29, 1905, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-01-29/ed-1/seq-54/.

17 “The Colonial Music Hall”

18 “A New Music Hall Opens To-Night,” New York Tribune, February 4, 1905, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-02-04/ed-1/seq-9/

19 “The Reappearance of E.S. Willard at The Knickerbocker,” New York Tribune, January 22, 1905, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-01-22/ed-1/seq-55/.

20 “Colonial Music Hall,” New York Clipper, February 18, 1905, 1230.

21 See Catherine Young, “‘A Very Good Act for an Unimportant Place’: Animals, Ambivalence and Abuse in Big-Time Vaudeville" in Performing Animality: Animals in Performance Practices, ed. Jennifer Parker-Starbuck and Lourdes Orozco (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015), 77–96.

22 “Colonial to Open Wednesday,” New York Tribune, February 5, 1905, 9. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-02-05/ed-1/seq-9/.

23 Colonial Theatre playbill, May 1, 1905, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library.

24 For Runnin’ Wild production facts, see “Runnin’ Wild – Broadway Musical – Original | IBDB,” . For an in-depth analysis of Black musical theater, see Eric M. Glover, African American Perspectives in Musical Theatre (New York, NY: Methuen Drama, 2024).

25 For a more detailed account of Johnson’s musicianship and Charleston compositions, see Seton Hawkins, “San Juan Hill and the Black Music Revolution,” Legacies of San Juan Hill, https://www.lincolncenter.org/feature/legacies-of-san-juan-hill/san-juan-hill-and-the-black-music-revolution.

26 Jayna Brown, Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 198. For more about the Charleston, see Marshall and Jean Stearns, Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994). For more on African American dance theory, practice, and history, see Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Thomas F. DeFrantz, ed (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002).

27 Brown, Babylon Girls, 198.

28 Eric M. Glover, African American Perspectives in Musical Theatre (London: Methuen Drama, 2024), 61.

29 Allen L. Woll, Black Musical Theatre: From Coontown to Dreamgirls (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 75. Also see Caseen Gaines, Footnotes: The Black Artists Who Rewrote the Rules of the Great White Way (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2021).

30 See Gaines, Footnotes, chapter 10 “Partial Ownership” and Woll, Black Musical Theatre, 84-85.

31 Woll, Black Musical Theatre, 88.

32 James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1930), 190, http://archive.org/details/blackmanhattan00john_1.

33 Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan, 190 and Woll, Black Musical Theatre, 85-91.

34 “The Chocolate Dandies: Opening Night Cast” Internet Broadway Database, .

35 Van Hoogstraten, Lost Broadway Theatres, 92.

36 Arthur Frank Wertheim, Vaudeville Wars: How the Keith-Albee and Orpheum Circuits Controlled the Big-Time and Its Performers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 269.